OTTAWA -- The Supreme Court of Canada will deliver a one-of-a-kind ruling on Friday on what it takes to be one of its own and it could trigger political shock waves across the country.

The high court will decide whether Prime Minister Stephen Harper's appointment of a semi-retired Federal Court of Appeal judge from Quebec passes constitutional muster.

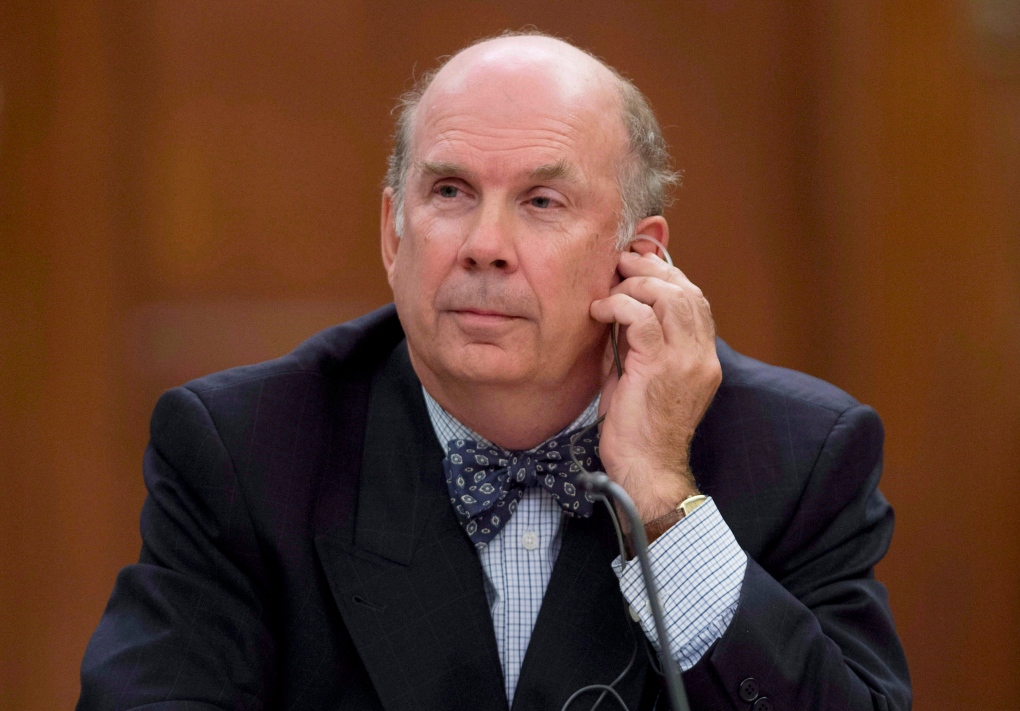

Harper's September nomination of 64-year-old Marc Nadon to fill one of three Supreme Court seats reserved for Quebec has been challenged by a Toronto lawyer.

Rocco Galati argues that Nadon does not meet the qualifications to fill one of the mandatory Quebec vacancies because he came from the Federal Court and not a Quebec court.

In an extraordinary move, Harper referred the matter to the Supreme Court.

Nadon has been strictly quarantined from the eight remaining justices and is staying away from country's highest courthouse.

The Tories also passed legislation that would permit the appointment of a jurist who was currently, or had been, a member of a provincial bar with at least 10 years standing -- a provision that applies to Nadon.

If the Supreme Court sides with Galati, it would be a serious political rebuke to Harper and have implications for the next Quebec vacancy that will present itself later this year.

If Nadon's appointment is upheld, the ruling could become an issue on the Quebec election trail.

Regardless of the actual ruling, there could be a strong response among sovereigntists who likely won't approve of being told how Quebec should interpret the special provisions of the Supreme Court Act. The act lays out the rules on how Quebec's three justices are selected.

Factums filed in court for the case offered up some dire scenarios, including that of a Quebec separatist movement reinvigorated by legal machinations in Ottawa and a Supreme Court that would be filled with partisan appointees by the government.

In all, the court heard from seven interveners, including the federal and Quebec governments, as well as an association of provincial court judges and constitutional experts.

The political ripples will flow from a very specific set of legal issues that lie at the core of the case.

It all centres on two specific sections of the Supreme Court Act -- sections that were rewritten by the Conservative government and were buried in its 300-page plus omnibus budget implementation bill last year.

Section 5 of the Supreme Court Act deals with the general eligibility of nominees. It allows for the appointment of a former or current member of the bar or a member of a superior court of a province or a barrister with 10 years standing in the province.

Section 6 deals specifically with the appointment of the three mandatory Quebec appointees. It says appointees must be from Quebec Superior Court, its Court of Appeal or among the advocates of that province with 10 years standing.

The issue of Federal Court judges is not specifically addressed and that's a major point of argument among the litigants.

The case will turn on how the Supreme Court chooses to interpret how the 10-year membership requirement for the Quebec bar applies to Nadon, whose career as a lawyer in the province spanned two decades.

The court has also been asked to consider whether the government had the constitutional right to amend the Supreme Court Act.

Galati argued there was no "constitutional imperative" to extend eligibility to "every single lawyer in the country" to be a candidate for the Supreme Court.

"It's about the constitutional requirements to maintain the federalism that was brokered between the provinces and the federal government," he argued.

Quebec government lawyer Andre Fauteux argued it was "absolutely, unequivocally unacceptable for Quebec" to accept a federal appointee.

He told the seven justices hearing the case in January that the 1875 compromise that birthed the Supreme Court required two of seven judges to be from Quebec. That was changed to three of nine in 1949.

Allowing the rules can to be rewritten by the federal government or any single province, said Fauteux, would eliminate "a huge stretch of history regarding the Canadian constitution."

The federal government argued that interpreting the Supreme Court Act to bar any Federal Court judge from being appointed to the top court would reduce the already small pool of qualified judges.

Of the eight sitting Supreme Court justices, Marshall Rothstein of Winnipeg, also came from the Federal Court of Appeal. He was appointed by Harper in 2006.

Rothstein's Manitoba credentials were based on a legal career in the province from 1966 to 1992 when he was a partner in a law firm and a lecturer in transportation law at the University of Manitoba. He was appointed to the Federal Court trial division in 1992.

Rothstein has recused himself from the current case. He has given no public reasons for that.

That means his seven remaining colleagues will decide the case, eliminating the possibility of a 4-4 split as well as the perception of a conflict of interest on Rothstein's part.