TORONTO -- Canadians self-reported 223,000 hate-motivated incidents in 2019, according to newly-released Statistics Canada data, but police only investigated fewer than one per cent of them as hate crimes.

“We are in the middle of a hate crime crisis,” Evan Balgord, executive director of the Canadian Anti-Hate Network, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview on Wednesday.

His group requested and analyzed StatCan data and published its findings last week. The group said there was a “startling disparity” between self-reported hate crimes and those reported by police.

Statistics Canada said law enforcement only reported 1,946 hate crimes in 2019, the year with the most recently available in-depth data.

But there were an estimated 223,000 self-reported hate crimes in Canada that same year, according to newly-released data from 2019 General Social Survey, with victims saying 130,000 of those incidents involved violence.

“The police reporting makes it seem like it’s a much smaller issue, when in fact, it's like a hundred times worse -- which is just wild,” Balgord said. “It shows that the average Canadian is more likely to be the victim of what they perceive to be a hate crime than they are to be hurt in an automobile accident.”

Of the staggering 223,000 incidents, fewer than a quarter of them – or 48,000 – ended up being reported to police.

There was a number of reasons for the discrepancies between what people said happened to them and what the police reported. The Canadian Anti-Hate Network said reasons could’ve included potential language barriers, victims’ potential distrust of the police, or a belief that officers wouldn’t believe them.

Other reasons stemmed from how police decided what qualifies as a hate crime, the group added.

In order for law enforcement to record hate crimes, the incidents first need to be reported to them. Then, officers classify the incident as either a “suspected” or “confirmed” hate-motivated crime, which can change as evidence is gathered. StatCan says that hate crimes are classified based on the perception of the accused, not by the characteristics of the victim.

For example, if anti-Muslim language is used during an assault, the hate crime will be considered anti-Muslim whether or not the victim is Muslim.

MOST VICTIMS WERE WOMEN

Two thirds of the 223,000 self-reported hate crimes in 2019 were either in Ontario and Quebec; with about 14 per cent of all incidents taking place in Alberta.

Overall, women were more likely to be targeted than men. One in four victims reported having a disability. About half of all incidents related to a victim’s race or perceived ethnicity, with approximately 20 per cent of all self-reported attacks being over religion.

Around 130,000 of all self-reported hate crimes involved violent crimes, 56,000 involved a break-and-enter or vandalism, with 38,000 being cases of theft of personal property.

The 2019 data is based on an in-depth survey which is released every five years and Balgord points out it’s already well out of date now.

“We shouldn't only be getting this every five years… that’s too slow,” Balgord said.

Throughout the pandemic, hate crimes and racially motivated attacks against Asian-Canadians, Muslim Canadians, Jewish Canadians and other racialized groups have skyrocketed across the country and in the U.S.

In 2020, Statistics Canada found police reported 2,669 hate crime incidents, but the findings were part of a much smaller-scale study of several metropolitan areas.

CALLS FOR FASTER DATA, STRONGER HATE CRIME LAWS

The Canadian Anti-Hate Network is calling for more regularly conducted surveys and stronger clarity in the Criminal Code specifically listing hate crime as an offence, and demanding all political party leaders’ support for legislation that compels social media giants to proactively remove hate from their platforms.

“If we can significantly crack down on online hate, we will see a reduction in in-person hate violence,” Balgord suggested.

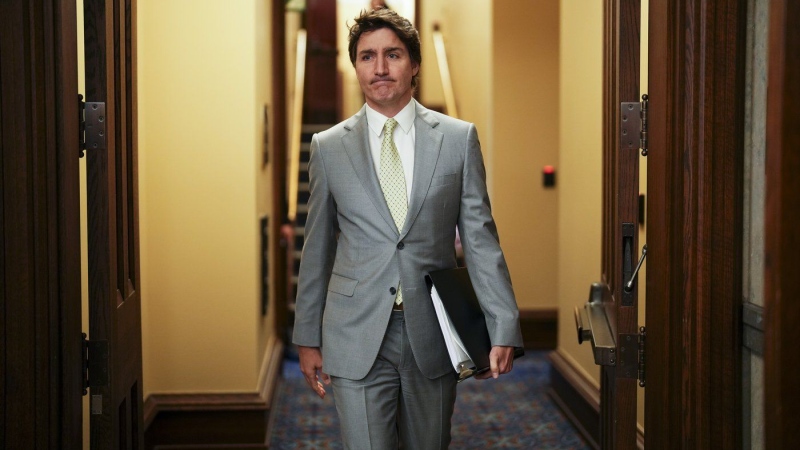

He and his group support what was in the Liberals’ platform released on Wednesday, which committed to an action plan for hate and included the National Council of Canadian Muslims’ recommendation to create a fund for the victims of hate attacks.

But Balgord said it’s far from enough and tackling hate crimes should be a clear non-partisan issue.

In the meantime, the Canadian Anti-Hate Network has applied for a grant under the Community Support, Multiculturalism, and Anti-Racism Initiative to conduct bi-annual surveys on hate issues with recognized polling firms.