A Canadian entrepreneur says he feels betrayed by his adopted country, after Ontario financial regulators allegedly put his safety at risk by co-operating with Chinese police in a fraud investigation.

Edward Gong, 57, is suing the Ontario Securities Commission (OSC) for violating his Charter rights by co-operating with a “known human rights abuser,” when it signed an agreement to investigate him with China’s Ministry of Public Safety (MPS) in 2017.

The lawsuit, filed in Ontario Superior Court, claims the commission used tainted evidence and shared information on Gong and his company with the MPS that was “unabated, unregulated and unlimited in scope and use.”

Gong alleges in the claim the OSC treated him “as though he belonged to China, instead of recognizing his rights as a citizen of Canada.”

Gong made his fortune by manufacturing health supplements in Toronto, then selling the products to customers in China. At the height of his success, Gong says he employed more than 600 people in his company which generated revenues that topped $200 million.

The OSC says it will not comment given that the matter is before the court. It has yet to file a statement of defence.

FAILURE TO PROTECT

In an interview with CTV News last month, Gong said that Canada failed to protect him.

“I believed that Canada was a country that could offer peace and safety. That it could protect our rights. I don’t think that anymore,” said Gong through a Mandarin translator.

Gong’s statement of claim was filed in February, two years after criminal charges of fraud and money laundering against the tycoon were withdrawn. However, his company, Edward Enterprise International Group, pleaded guilty to operating a pyramid scheme and forging documents and was fined $1 million and forfeited nearly $15 million in assets to the Canada Revenue Agency in 2021.

The former opera director-turned-mogul has lived in Canada for more than two decades and became a Canadian citizen in 2008.

Emails seen by CTV News indicate that at one point, OSC alerted Chinese police that Gong may be in China. Gong alleges in the claim that the Ontario regulator put him at risk of being “disappeared” and subjected him to the possibility of indefinite detention, torture and even death.

At a time when foreign interference is dominating parliamentary debate, Gong’s lawyer, Joel Etienne, says his client’s case shows Chinese interference extends beyond election meddling.

“This shows that (Chinese Communist Party) infiltration and partnership within the Canadian apparatus is more embedded and much more integrated,” says Etienne. “This is not about a couple of rogue MPs.”

AFFLUENCE AFFORDS ACCESS

Prior to the OSC investigation, Gong was considered by many to be a success story. In addition to his health supplement business, he owned two hotels in Toronto and a Mandarin-language television station based in Scarborough, Ont.

He says that officials from the Chinese Consulate General in Toronto would visit him at the station to inquire about his programming and cultural pageants he produced.

His affluence also garnered invitations to political fundraisers where he rubbed shoulders with Canadian leaders. A widely-circulated photo shows him watching Prime Minister Justin Trudeau make dumplings at a fundraiser in 2016.

Gong says since becoming a Canadian citizen, he’s donated a total of $10,000 to both federal Conservative and Liberal candidates and that consular officials never directed him to contribute to specific individuals.

However, Gong wonders if he may have unknowingly said something that offended China on one of his television shows.

“I do things according to Canadian values. I may have hurt someone’s feelings - that’s what I suspect,” said Gong.

His lawyer believes Gong was targeted because he had renounced his Chinese citizenship to become a Canadian and had become a success without relying on the Chinese Communist Party.

“When you become very big and very successful you’re seen as a rival to the CCP...and if you’re not their partner, then you’re the enemy,” Etienne said.

IN CHINA’S CROSSHAIRS

The Chinese Consulate in Toronto has not responded to a request for comment on Gong’s lawsuit

But court documents show that Gong first appeared on China’s radar in October 2015, when 11 people were arrested in Hunan province for recruiting members in a pyramid scheme. According to police in Shaoyang City, they were selling fraudulent shares in a company known as “O24 International Pharmacy Federation of Canada Edwards Business Group.” China’s Ministry of Public Safety (MPS) then issued a warrant for Gong’s arrest and detention.

Chinese police passed their dossier on to New Zealand’s embassy in Beijing, with a request to freeze assets and recoup funds it believed were being laundered in that country.

New Zealand police then requested help from Canada to surveil Gong and gather more information about his company. Through a civil proceeding in New Zealand, Gong was forced to forfeit more than $60 million in assets.

Affidavits state that the Chinese government took the lead in analyzing the financial data collected by authorities in all three countries.

A substantial portion of the case against Gong was based on information obtained from the 11 men and women arrested and convicted in China. Gong’s legal team hired an investigator to travel to Hunan province to interview some of the suspects who had been released from jail.

In transcripts provided to CTV News, some said they were victims of police threats and extortion and forced to confess. One man said he was detained for 37 days without charge, while a woman said her friend’s son was denied entrance into university because they knew her.

That evidence is part of nearly 1,500 pages of documents filed in Gong’s lawsuit against the OSC.

MONEY LAUNDERING AND JUNKETS

The disclosure filed as part of the lawsuit includes emails and reports between RCMP liaison officers with the Canadian Embassy in Beijing and OSC investigators in Toronto.

An email dated from October 2016 revealed that RCMP’s Integrated Market Enforcement Team that works with the OSC concluded after a preliminary investigation there wasn’t enough evidence to pursue criminal charges against Gong at the time. But that seemed to change after a meeting in Beijing with China’s lead investigator, You Xiaowen, the deputy director general of the Fugitive Affairs Office of the MPS.

Just before Christmas of 2016, RCMP liaison officer Sean Jorgensen met with You. According to Jorgensen’s report, the deputy director general believed that the majority of funds from the pyramid scheme, about 1 billion Yuan, were actually sent to Canada, not New Zealand.

Jorgensen wrote: “(General) You noted that money laundering is a significant priority for the RCMP and proposed that Canada and China launch a joint investigation of this case.”

Before a joint agreement was even signed, OSC investigators traveled to Hunan province to interview witnesses in prison in February 2017.

Gong’s lawsuit claims OSC conducted its interviews in the presence of MPS officers and refers to the trip as a “luxurious” junket.

JOINT AGREEMENT SIGNED

According to documents filed in court, the OSC signed an agreement to disclose and exchange information with Chinese police on April 4, 2017. The agreement states that any evidence provided by the commission will be used for “similar law enforcement and prosecution of Gong and other individuals under the Criminal Law of the People’s Republic of China.”

In 2017, China passed its National Intelligence Law, requiring Chinese organizations and citizens to help with state intelligence work, no matter where they lived in the world.

According to Gong’s claim, RCMP officer Jorgensen flagged concerns about sharing information with China but was pushed out of the liaison office in Beijing. He declined a request for an interview because the matter is before the court. Jorgensen is now back in Ottawa in the role of Director of Operations of the National Security and Intelligence Committee of Parliamentarians. NSICOP is one of the committees currently tasked with investigating Chinese political interference in Canada.

WATCHED BY BEIJING

After the joint agreement was signed, General You and a team of Chinese agents flew to Toronto in October 2017. Gong’s lawsuit alleges the OSC “took no steps to restrict” the conduct of the MPS while they were in Canada.

Two months later, search warrants were executed and Gong’s property was raided. Gong was arrested after stepping off a flight at Pearson International Airport on Dec. 29, 2017.

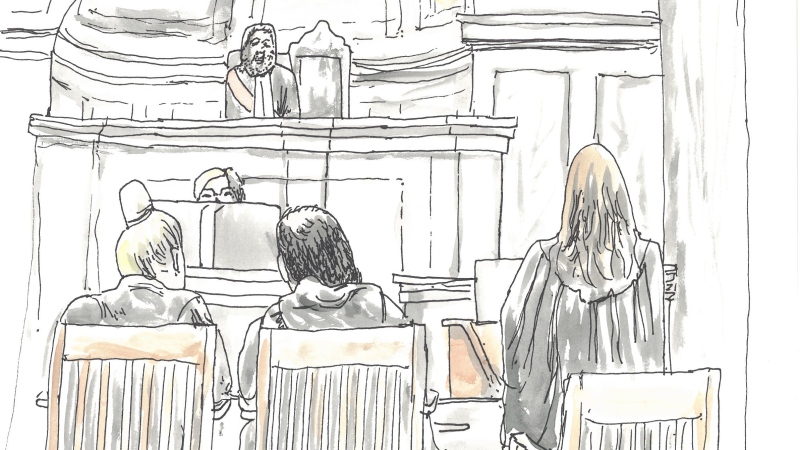

The lawsuit claims that before Gong was taken to the courthouse at Toronto’s Old City Hall, OSC officials attempted to walk him through the nearby Eaton Centre for a “photo-op” instead of using the proper entry for prisoner delivery.

Gong also alleges that OSC staff accessed and distributed at least 5,890 potentially privileged documents to investigators in New Zealand and China. Etienne says the documents contained private information on Gong’s customers in China, but also his employees in Canada. It’s not known how China treated these individuals.

The entrepreneur says the ordeal has left him afraid that his every move is being watched by Beijing.

“Whatever I do, the Chinese authority knows about it. Information travels fast and I’m a person that a lot of people pay attention to, so I have to be very careful,” said Gong.

SHADES OF OPERATION FOX HUNT

Ina Mitchell is a Vancouver-based author who has worked with law enforcement in researching Chinese interference. Although there is no reference to it in the court documents, Mitchell says Gong’s case bears the hallmarks of China’s Operation Fox Hunt. The operation was launched in 2014 and targets Chinese public officials and business people accused of financial crimes and corruption.

Communist state television and pro-China media often broadcast the capture of these alleged fugitives who live overseas.

Mitchell says Gong would have been a high-level target for the Chinese Communist Party “to leverage” because he owned a television station and could get access to Canadian politicians.

Public Safety Canada says on its website Canada has “imposed increasingly stringent criteria” on this program since 2015, because it's widely believed the Chinese government uses Operation Fox Hunt to stifle regime criticism.

Despite the parameters set out by Public Safety Canada in 2015, the OSC co-operated with China and investigated Gong with the assistance of the Mounties two years later.

Mitchell says she finds it disturbing that the OSC was willing to “deliver Gong into danger.”

In an email exchange in May 2017 filed in court as part of Gong’s lawsuit, OSC senior litigation counsel Cameron Watson wrote to You that it would be “prudent” to alert him of the possibility that Gong was in China.

It emerged later that Gong had not left Canada, but the lawsuit says the OSC deserves “repudiation” for providing information that could have facilitated Gong’s disappearance into the hands of Communist state police.

“It’s shameful. He’s a Canadian, not a permanent resident. What message are we sending to Chinese Canadians if a citizen isn’t safe?” Mitchell says.

ALLEGATIONS OF RACISM

Gong also alleges discriminatory treatment, claiming that it is “highly unlikely that a Canadian citizen born in Canada of European and/ or of White background, who was accused of financial crimes would have been treated in such a manner.”

Etienne says Gong was not protected by his country, which permitted a “dictatorship” to follow, monitor and investigate him in Toronto.

The RCMP did not comment directly on the Gong case, but in an email to CTV News, the Mounties say they’re aware that foreign states may seek to intimidate or harm communities or individuals within Canada.

The RCMP says it does not assist with operations such as Fox Hunt because “they are considered illegal in Canada.”

Calvin Chrustie previously investigated transnational crime cases as an operations officer with the RCMP.

The security consultant says he’s surprised by the OSC’s misplaced confidence in China’s justice system.

“The Chinese government does not share our respect for values or due process, morals and ethics,” says Chrustie. He says during that period of time in 2016 and 2017, there should have been awareness among law enforcement, military and politicians of the high risks involved with collaborating with the Chinese government.

Chrustie says the Gong case shows that Canadian authorities have not done a sufficient job in sharing vetted intelligence with the public of the many ways China can exert control over its diaspora. Our naiveté, Chrustie says, makes Canada vulnerable.

“An equal threat to China is our failure to ensure Canadians are aware of the seriousness of the threat,” Chrustie said.

“We don’t have the same level of security intelligence proficiency. They’ve been playing chess. We’re playing checkers.”