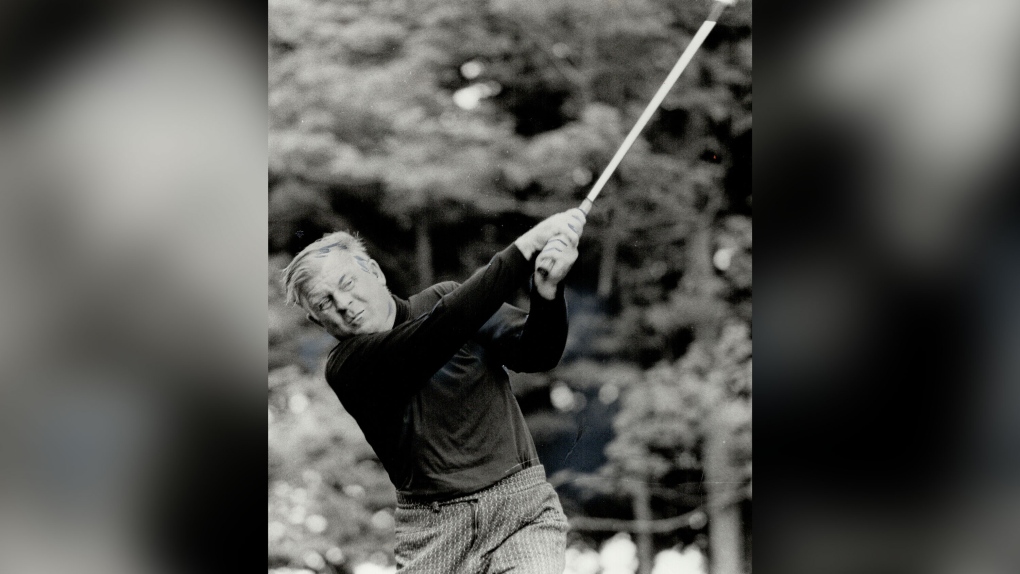

Whether it's because of his funky clothing, eccentric personality or highly distinctive swing, Moe Norman -- dubbed golf's "Rain Man" -- didn't fit into the sport's traditional mould.

"Like Raymond [Babbitt], Moe spoke in staccato bursts," golf coach and author Tim O'Connor, who has written a book about Norman, told CNN Sport, as he compared the Canadian golfer to the Oscar-winning film's leading character.

"'Golf's like a walk in the park, walk in the park' ... He repeated himself," adds O'Connor, describing Norman's speech mannerisms. "He had this sort of sing-songy lilt to his voice and his eyes would kind of go all over the place."

But like Babbitt, Norman's unusual personality was accompanied by a touch of genius -- such was his golf skill it earned him the self-proclaimed title of "the best ball striker who ever lived."

In an age when golfing legends like Ben Hogan, Gary Player and Lee Trevino regularly swept up major titles, Norman only appeared in the Masters twice, but his accuracy still attracted the respect of many of his fellow players, and has earned him cult status.

Through his highly distinctive "single plane swing" -- which he created, practised and perfected himself and which current players, such as U.S. Open winner Bryson DeChambeau, have now taken elements from -- Norman was able to repeatedly hit the same spot on the fairway or green with unerring regularity.

Despite that, the Canadian isn't a household name.

Whether it was shyness around newcomers, his "eccentric" personality or the fact he never enjoyed the same success on the PGA Tour as his contemporaries, those who knew him say Norman often just didn't fit in.

"We live in this culture in which we celebrate celebrity and those who achieved at the highest level. Moe did not do that," O'Connor -- author of "The Feeling of Greatness: The Moe Norman Story" -- told CNN Sport. "Moe was just this beautiful character. He was a very complicated person.

"And I think maybe if Moe came around in the last 20 years, maybe we would have embraced his eccentricities and he could have flourished a little bit more."

DIFFERENT FROM THE OUTSET

Born in Kitchener, Ont. in 1929, as a child Norman enjoyed spending his days with friends or playing hockey. However, once he discovered golf, his life began to change, but at some cost O'Connor says.

As Norman's interest in golf blossomed, fueled further by regularly caddying at a local club, his working-class family questioned why he chose to play a sport often associated with the more elite members of society.

Despite Norman's ever-increasing passion for the game, his family "totally rejected it," resulting in Norman's ignoring their support when they eventually came to watch him years later, according to O'Connor.

"His family was opposed to this thing that he loved," O'Connor explained. "And it really caused the schism in the family and really total estrangement."

During his late teens and early twenties, Norman dedicated himself to perfecting his "single plane swing," so that he could routinely hit the ball wherever he wanted with remarkable accuracy.

The "single plane swing" was Norman's attempt to improve shot efficiency and remove the number of variables involved. Addressing the ball, Norman ensured the club's shaft position was maintained at impact and he did so by using a wide stance, outstretched pose and aligned hands. It was a swing that synchronized the movements of the hips, shoulders, arms and hands.

Such was his dedication to perfecting his swing, there are stories of Norman spending so much time on the practice range that by the time he left, his palms were bloody from the repetition of his practice.

Later in his career, Norman would run clinics for fans, during which he would showcase his accuracy. He'd even attract the attention of fellow professionals, such was his precision.

Yet for Norman, winning tournaments wasn't the end goal. The process of clean ball-striking was more "spiritual" for him -- something he described to O'Connor as being the "the feeling of greatness."

Professional Todd Graves spent a year trying to learn Norman's swing from a videotape given to him by a friend, but he says his first experience of seeing the Canadian hitting balls close up still blew him away.

"I don't think I've ever seen anybody do what Moe could do to a golf ball, as far as the consistency of the flight, the windows he would hit the golf ball and with just such simplicity," Graves -- co-founder of 'Graves Golf Academy' -- told CNN Sport.

'VERY STRANGE'

Only really trusting of his closest friends, Norman could come across as "very strange" if you didn't know him, according to O'Connor, who recounts how the golfer once ran from a restaurant mid-interview -- for Norman's own book -- simply to alleviate the uneasiness that he experienced around a particular line of questioning.

Given these personality traits, O'Connor says some people have subsequently hypothesized that Norman might have been on the autism spectrum.

Included on the list of symptoms for autism by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention are avoiding eye contact and wanting to be alone, repeating or echoing words or phrases or repeating "words or phrases in place of normal language," and not being able to relate to others or "not have an interest in other people at all." Every one of these symptoms, in retrospect, could have applied to Norman.

However, in researching his book, O'Connor uncovered another possible theory to explain Norman's personality traits.

When Norman was about five years old, he was out sledding with a friend and, as they slid across a road, he was hit in the forehead by the tire of a reversing car, according to O'Connor.

Because there were no broken bones, his family didn't take him to the hospital and the neuroscientists O'Connor interviewed theorized that Norman's different personality might have been due to a frontal lobe brain injury.

"He knew what was important in life. He was just unable to express it in ways that a lot of people would. He didn't get jokes at all. And he just lived within this very confined area of golf and came off as a strange character to a lot of people," said O'Connor.

FEELING AT HOME

On a golf course, however, Norman was in his element.

O'Connor recalls stories of Norman chatting easily with spectators during rounds and even taking bets from onlookers about whether he could bounce a ball off his driver more than 100 times or hit a ball into their shirt pockets.

Graves, who is also the executive producer of an upcoming documentary on Norman, remembers speaking to former PGA of Canada professional Henry Brunton about the change in Norman's demeanor on and off the course.

While Brunton describes Norman as being "supremely confident" with a club in his hand, when faced with just his fellow players in the clubhouse, he was "like a 12-year-old kid."

"He was intimidated. He didn't understand how to act around other players. He was so intimidated by his peers," Brunton told Graves.

Although he enjoyed great success in Canada, Norman struggled on the bigger stage of the U.S. PGA Tour.

While he racked up over 60 wins on the Canadian Tour, Norman played in 27 events on the PGA Tour across 15 years, finishing in the top 10 only once, earning just US$7,139.

He also played in five Senior PGA Tour events, in which he earned $22,900 in prize money.

He only appeared twice in the four majors, playing in the Masters in 1956 and 1957.

According to Graves, adjusting to life on the road in a new country and without the familiarity of his support system proved tough for Norman.

He also had to endure at least one alleged incident of bullying from unnamed fellow professionals. In just his second year on the Tour, he was cornered by two players in the midst of a tournament -- in which Norman was in contention -- and told: "You got to stop fooling around, take a caddy, stop with the big tees," according to O'Connor.

The PGA of America -- which ran the tour before the modern day PGA Tour was established in 1968 -- has not responded to CNN's request for comment.

"That led to a lifetime of Moe feeling that he didn't feel that he belonged and he was not welcome there," added O'Connor. "Because he just had this sense that they didn't like him. And if Moe had the sense that people had it in for him, or that they were up here and he was here or if he felt slighted by you, he would write you off."

In later life, money was also an issue for Norman. According to Golf Digest in 1995, the golfer was living in a $400-a-month motel room and kept his clothes in his car. Later in life, golf manufacturer Titleist paid Norman US$5,000 a month for the rest of his life due to his service to the sport.

Just a few years later, in 2004, Moe Norman died at the age of 75. And although he did not achieve the tournament-winning success that his contemporaries enjoyed, the legacy of this true golfing pioneer and self-proclaimed "best ball striker who ever lived" should not be forgotten.