People who are transgender are significantly less likely to receive cancer screenings than the general population, raising their risk of developing the disease undetected in situations that could have been preventable.

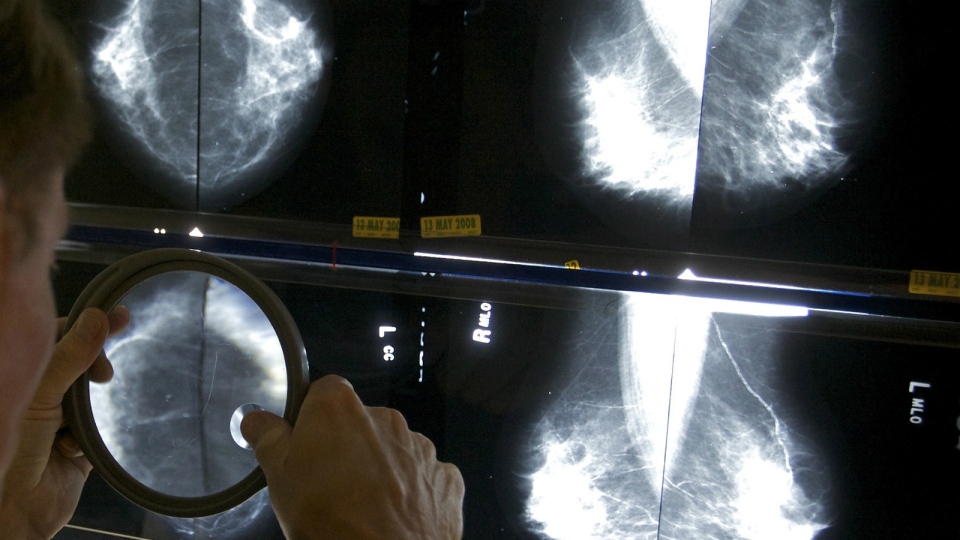

A new study published Wednesday in the journal Canadian Family Physician found that about 33 per cent of eligible transgender patients had been screened for breast cancer, compared to 65 per cent of other eligible patients.

Screening rates for other types of cancer presented similar differences, with transgender patients being about 60 per cent less likely to have been screened for cervical cancer and 50 per cent less likely to have been screened for colorectal cancer, after adjusting for age and other risk factors.

“If they’re not getting screened, they have a higher risk of developing a cancer that we know could be prevented,” the study’s lead author, Dr. Tara Kiran of St. Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, told CTV News in an interview.

The study was based on analysis of 120 transgender patients and more than 20,000 other patients at St. Michael’s, all of whom were eligible for screening for breast, colon and/or cervical cancer. Kiran said it began when doctors there realized transgender patients were being misclassified or outright missed during outreach efforts to get patients to come in for screenings – even though the hospital’s staff pride themselves on their efforts around transgender care.

“If it’s happening here … I know it must be happening across Ontario and across Canada, and potentially worldwide,” Sue Hranilovic, a primary health care nurse practitioner at St. Michael’s, said in an interview.

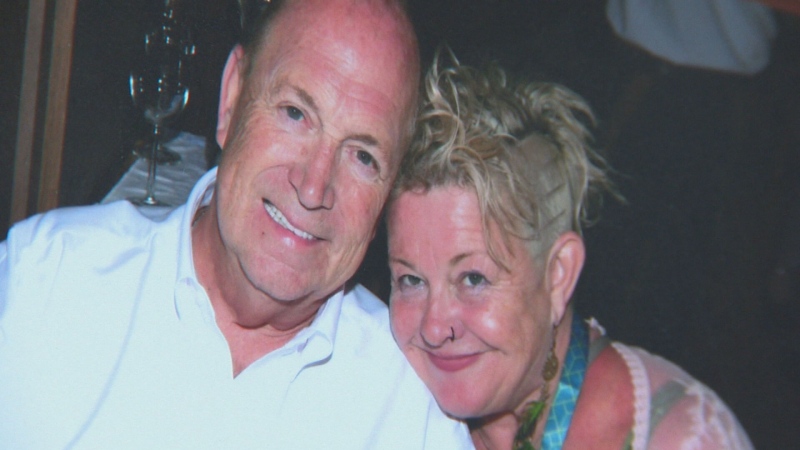

Patients’ lack of awareness can also play a role. That was the case for Cat MacDonald, who transitioned to female in 1996.

MacDonald said in an interview that her doctor at the time was essentially learning about trans care along with MacDonald, and never suggested that she be screened for breast cancer – even though the hormones she was taking put her at greater risk of contracting the disease.

“I was never tested, never screened. I never had a mammogram until I changed doctors,” she said.

“You would think that the medical profession would have more awareness of trans issues, but obviously they don’t.”

Some transgender patients can also be hesitant to speak up about their transgender status, leaving doctors without any reason to think about preventing male cancers in female patients, or vice-versa.

“I go to a doctor who doesn’t know me [and] my documentation shows female, the doctor is not going to think to screen for prostate cancer,” MacDonald said.

“I know that most patients do not like to admit they are trans, but there are some times when it’s necessary.”

Kiran suspects a few additional reasons for the discrepancy in screening rates, largely blaming the health-care sector for not having transgender patients’ histories top-of-mind. Guidelines for transgender patients are also different from guidelines for screening other patients.

“We may be treating them appropriately in the gender that they’re choosing to be now, but not thinking about some of the sex organs that they still have,” she said.

The Canadian Cancer Society has recently launched a campaign encouraging people who are transgender to get screened for cancer. A public service announcement produced for the campaign stars Rita OLink, a transgender woman living in Sudbury, Ont.

“As a trans person, I know how difficult it is to even approach the idea of being screened for any sort of cancer,” OLink told CTV News.

“We need to break down the barriers.”

Like MacDonald, OLink believes fear of how people who are transgender will be received by medical professionals is a significant barrier to going for screenings.

Ultimately, it seems, improving screening rates will require a concerted effort by health-care professionals to better identify transgender patients and by the patients themselves to be aware of their risks.

“Cancer can kill – and if people are not willing to speak up, then nothing’s going to change,” MacDonald said.