Organic cotton tampons are often advertised as safer alternatives, but a study Friday said they are not better than regular tampons at preventing toxic shock syndrome.

Menstrual cups can also raise the risk of toxic shock, and should be boiled in between uses, said the report in Applied and Environmental Microbiology, a journal of the American Society for Microbiology.

Women have long been advised to change tampons regularly to avoid the risk of toxic shock syndrome, a rare but life-threatening condition that arises from a bacterial infection.

Symptoms may include fever, vomiting, rash, muscle aches and organ failure.

In recent years, a number of new female hygiene products have hit the market, including tampons made from organic cotton and menstrual cups that can be rinsed between uses.

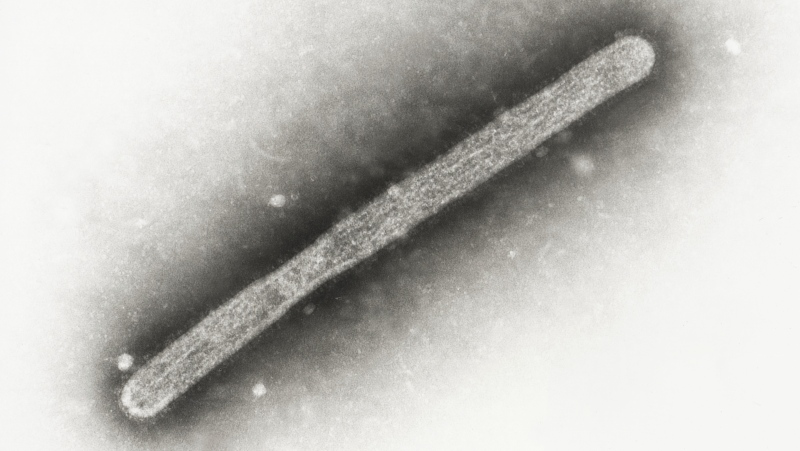

To see how they measured up, researchers tested 11 kinds of tampons and four menstrual cups in the lab to study their effect on growth of a pathogen called Staphylococcus aureus, and also toxic shock toxin 1 (TSST-1) production.

They inserted the tampons and cups into plastic bags, injected a liquid and a trace of bacteria isolated from a patient who had toxic shock in 2014, then sealed the bags and left them for eight hours.

They found it didn't seem to matter what kind of material was in the tampon, rather it was the amount of air in between the fibers that seemed to raise the risk of bacterial growth.

"Our results did not support the hypothesis suggesting that tampons composed exclusively of organic cotton could be intrinsically safer than those made of mixed cotton and rayon," said Gerard Lina, professor of microbiology at University Claude Bernard, in Lyon, France.

"We observed that space between the fibers that contributes to intake of air in the vagina also represents the major site of S. aureus growth and TSST-1 production."

Meanwhile, menstrual cups seemed to allow even more bacteria to grow than tampons, again likely due to the additional air involved.

At least one case has been documented in scientific literature of a woman coming down with toxic shock after using a menstrual cup.

"Over the years, it was postulated that perhaps if tampons were made from natural materials, toxic shock would be averted. The new research recently published clearly illustrates that this is not true," said Adi Davidov, director of gynecology and robotic surgery at Staten Island University Hospital in New York, who was not involved in the study.

"Toxic shock can occur with any tampon material and even more frequently with the menstrual cups."

According to Jill Rabin, co-chief of the division of ambulatory care at Northwell Health, a network of medical providers in New York, women should change tampons frequently.

"If tampons and menstrual cups are used be sure to see your doctor at the first sign of any fever, chills or rash, and of course, remove the cup or tampon immediately."