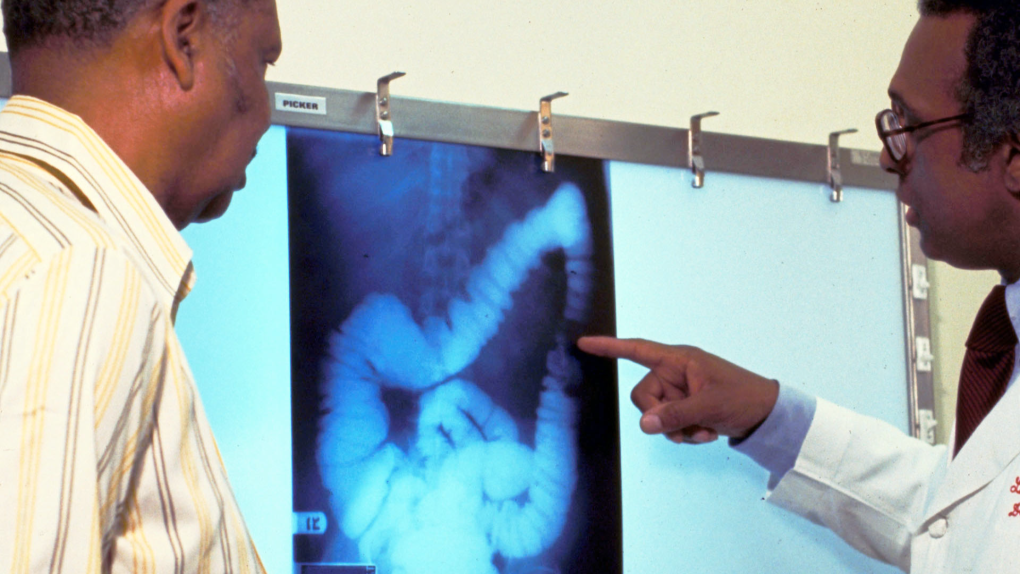

A new study has found that colorectal cancer rates continue to rise in younger Canadians. The researchers suspect that a heavier population may be to blame.

The study published Wednesday in JAMA Network Open looked at data from all Canadians diagnosed with colorectal cancer between 1969 and 2016.

The researchers found that the risk of colorectal cancer in the youngest cohort of men (those aged 20 to 29 in 2015) was more than double that age group’s risk in 1936. For women, the incidence rates were also higher in younger cohorts, although the difference was not considered significant.

Rates of the disease in Canadians under 50 have been steadily increasing since the mid-1990s, while rates have been mostly falling for those over 50 since the 1980s, according to the paper.

International studies have found a similar pattern. A study published in The Lancet earlier this year looked at rates among 143 million people in Australia, Canada, Denmark, Norway, New Zealand, Ireland, and the U.K. found the presence of the disease has declined overall in the past 10 years but has increased dramatically among those under the age of 50.

The authors of the new study, led by Dr. Darren Brenner of the University of Calgary, say an increase in colonoscopies for purposes other than cancer screening “cannot explain most of the new cases.”

“More likely, lifestyle factors associated with increased weight gain are fueling the rise in (colorectal cancer) incidence in this age group,” the authors write.

The paper concludes that more research is needed to decide whether screening recommendations should change.

The Canadian Association of Gastroenterology recommends that people whose parents, children or siblings have been diagnosed with colorectal cancer get screened between ages 40 and 50, or 10 years earlier than the age at which their relative was diagnosed, whichever is earlier.

The Canadian Preventative Task Force on Preventative Health Care recommends screening every two years for those between 50 and 74.

People of all ages are encouraged to watch for changes in bowel movements, signs of rectal bleeding or lumps in their abdomen, which could be signs of the disease.

The new study’s authors write that although screening younger people could reduce mortality, guidelines need to take into account potential negative consequences of screening including the invasive nature of colonoscopies and a possible increase in wait times for individuals at higher risk.

Colorectal cancer refers to both colon and rectal cancers. In 2017, an estimated 26,800 Canadians were diagnosed with the disease, according to the Canadian Cancer Society. The five-year survival rate is estimated at 63 per cent for men and 65 per cent for women.