TORONTO -- It's been a long, sometimes painful journey since CTV’s W5 first reported on a controversial new theory about multiple sclerosis 10 years ago.

The theory of chronic cerebrospinal venous insufficiency, or CCSVI, was developed by Italian vascular surgeon Paolo Zamboni, who suggested that MS patients have abnormal veins that fail to properly drain blood from the brain and spinal cord. Opening those vessels, he reasoned, could restore blood flow and relieve symptoms -- a procedure widely known as "liberation therapy."

The theory became one of the most bitterly contested in recent medical history, embraced by desperate patients and scorned by doctors.

Yet, every year on the anniversary of the program, MS patients write emails to say the experimental therapy changed their lives for the better.

Many living with the disease had previously accepted the medical community’s consensus on the cause of the condition -- an autoimmune attack that could be controlled with medications.

But once CCSVI entered the picture, many patients demanded scientists pursue Zamboni’s new approach and forced research agencies to redirect millions of dollars into new CCSVI treatment studies. They had a powerful voice, since there are some 77,000 Canadians with MS -- one of the biggest causes of disability in Canada.

From the very beginning, many in the neurological community denounced the theory and treatment. Studies that followed painted conflicting pictures, with the consensus emerging that while CCSVI exists as a condition, treating it has no effect on MS symptoms.

HOPE OR HYPE?

It is safe to say that, a decade later, no one is happy with how the events around CCSVI unfolded.

"It's a bad chapter," said George Ebers, a Canadian neurologist who watched the story play out from his post at the University of Oxford.

He places CCSVI in the same category as other debunked MS treatments such as bee venom therapy and hyperbaric oxygen.

"I was, in a short time, pretty convinced it would be like the others," he said.

Zamboni’s work was itself born of the desperation that comes with a multiple sclerosis diagnosis. When his wife Elena developed MS, he embarked on a search for an explanation for the disease.

Using ultrasound, he and his research team from the University of Ferrara in Italy began finding unusual veins, or malformations, in many people with MS. Some were in the neck. Some were in the chest. Some were narrowed or blocked by their shape or by valves so that the blood drained out slowly or flowed backward into the brain -- causing, he said, pressure in the veins upstream to rise, damaging the blood vessels and somehow leading to an immune reaction.

Zamboni proposed that reversing flow to normal was the key to treating the disease. To do this, doctors performed angioplasty -- inserting a balloon into narrowed or blocked veins.

In a key trial of 65 MS patients, the Italian team documented improvements in blood drainage, quality of life, and a decrease in MS attacks and the brain lesions used to measure the progression of the disease.

The improvements didn't always last. But Zamboni's message was simple. As he told W5, "In my mind, this was unbelievable evidence that further study was necessary.” Zamboni’s own wife was treated and her MS symptoms improved.

(Dr. Paolo Zamboni works at his research lab at the University of Ferrara in Italy in 2012. W5 / Avis Favaro)

Most neurologists quickly dismissed the treatment, however, noting that there was longstanding proof of the autoimmune origins of MS. They felt Zamboni, a vascular doctor, should have stayed in his lane.

"I'm not down on the idea of people being hopeful … but not the way this one evolved. It spun out of control," said Ebers.

He worries that there was another reason why patients quickly embraced the hope of CCSVI and were wary of their doctors: many believed physicians were too closely tied to the pharmaceutical industry, and therefore too quick to dismiss the new idea.

Ebers said his colleagues bear part of the blame for the breakdown in trust.

"They (neurologists) had lost the trust of the patient population ... because of links with the (drug) companies. That was the message they should have taken home and chewed on," he said.

THE PATIENTS

Thousands of MS patients frustrated with drug therapies wanted a try at what Zamboni was testing, even though it was in the earliest stages of research.

Clinics quickly opened up in Europe, the United States and even the Middle East, where patients were charged thousands of dollars for the treatment.

Sandra Birrell became part of a stampede of patients. MS had robbed her of the ability to walk, even at times to breathe. "I was two years away from a feeding tube," said the Victoria resident.

Doctors found she had malformed veins similar to those described in Zamboni's paper. She paid US$5,000 for the angioplasty at a clinic in Albany, N.Y., in 2010.

"I had incredible results. I was walking totally unassisted for the first time in over eight years," said Birrell.

While her muscle spasms improved, over time some of the benefits disappeared. Others remained and she still believes the treatment saved her from a terrible fate. "I haven't choked since the angioplasty," she said. "You can't placebo that."

There were an estimated 5,000 Canadian patients who sought treatment, with some posting jubilant post-therapy videos online. But there were many others who had no benefit, or improved only to later regress. Few had proper medical follow-ups after the therapy because doctors in Canada had no idea what to do for them. There were reports that two patients died.

Science tried to catch up to the frenzied patient response. Eventually, research data started to emerge. The majority of studies confirmed the existence of vein abnormalities in many of those with MS, but researchers also found them in some healthy people.

Some studies showed angioplasty seemed to improve balance and bladder control in MS patients, and eliminated cognitive fog experienced by some with MS. Other studies also showed a reduction in brain lesions. In many others, including a large Canadian trial led by Dr. Anthony Traboulsee at the University of British Columbia, there appeared to be no difference compared to a "sham treatment."

Zamboni himself led a team that conducted a four-year study called Brave Dreams, that concluded angioplasty of the veins was "safe, but largely ineffective" except for a sub-group of patients who showed enough benefit to warrant further study. More on this later.

Earlier this year, the Cochrane Reviews -- a respected international agency -- concluded that angioplasty for CCSVI in people with MS "did not provide benefit on disability, physical or cognitive functions or quality of life.”

Just as many neurologists believed it would all along, science had drawn a curtain on CCSVI.

MANY LINGERING QUESTIONS

If the theory is dead, explain that to the 200 scientists and patients who gathered in May to discuss blood flow and the brain at the Santa Anna Hospital in Ferrara, Italy.

Researchers from China, the U.S. and Europe attended the two-day conference hosted by the International Society for Neurovascular Disease (ISNVD), a non-profit association set up by researchers intrigued by Zamboni's initial work.

Those at the conference were drawn to the research and the unanswered questions it raised.

While many of the doctors who had tried their hand at angioplasty on those with MS abandoned the field, one who did not was Dr. Salvatore Sclafani. A senior interventional radiologist from New York, he was among those drawn into the CCSVI camp.

"I am convinced it improves function in a significant number of patients," he said.

But he says what was presented in the first study as a technically simple procedure turned out to be much more complex. Some patients had with even more vein problems. Without the usual path of research before treatment there was confusion on the best way to diagnose and treat patients – who were clamoring for the therapy.

“You don't want to have patients leading (the agenda for) research on ground-breaking new ideas. It didn't work well," said Sclafani.

Still, he is part of a group determined to learn more: "There are many medical ideas that were dead in the water that are now standard of care. We need to have skeptics to have progress, even when it seems that they sometimes obstruct progress," says Sclafani.

"I do not believe that no further studies are needed -- that is saying that knowledge stops," said Sclafani.

"We are seeing clinicians, eminent clinicians who … are interested in fluids and the vascular system," said Clive Beggs, a physiologist at Leeds Beckett University in the U.K. who also attended the meeting.

"Many clinicians have jumped to the conclusion (angioplasty) didn't work. To physiologists like myself, I look at those results and think, 'That's extremely interesting -- why did they improve at the beginning, and if they regressed, why did they regress?'"

The core idea is that, for a brain to be healthy, it must take in blood with its nutrients and oxygen and expel the used blood in an orderly fashion, with the veins regulating out-flow. Beggs collaborates with researchers pursuing the health effects of impaired blood flow.

"What we seem to be finding is if the blood can't get out, this intra-cranial compliance is impaired. How that manifests itself in disease is another matter," said Beggs, who says there are more questions than answers right now.

Canadian electrical engineer Trevor Tucker seems out of place at the Ferrara meeting. He spent his life working on guidance systems for rockets in Ottawa.

The link here is his son Andrew, who has MS. Frustrated with the lack of effective treatments, Andrew went to a clinic in the U.S. where he was diagnosed with restricted venous flow from the brain. He was treated with angioplasty nine years ago. Like many others, his symptoms improved at first - and then like many others, regressed. A second angioplasty worked better, and Tucker says Andrew remains well and symptom-free.

(Trevor Tucker, who worked as an electrical engineer in Ottawa, speaks to CTV News)

Curious about his son's experience, Tucker is now a newcomer to the field. Drawing on his knowledge of physics, he is working on a hypothesis that blocked veins down in the neck could play havoc with blood flow back inside the brain, leading says to a turbulent "scrubbing motion" deep inside the smaller veins of the brain where the lesions of MS occur.

"That is not healthy for any brain. I don’t care if it is MS or another disease," said Tucker.

He remains intrigued by Zamboni’s work and the intense controversy. "To pooh-pooh it at this stage ... is disappointing," said Tucker, who is starting to publish his work.

THE LATEST RESEARCH

Also at the conference was Mark Haacke, a scientist from Wayne State University who studies better ways to see inside the brain. He helped found the ISNVD the year after Zamboni’s work first went public.

Haacke, too remains undeterred by the firestorm over the theory. As imperfect as it may have been initially, he says, it opened the door to expanding the learning and understanding of the brain’s venous system.

"The more data I see here ... the more I know he's right. There is some form of chronic hypertension (linked to certain brain diseases) ... but we don't know where it comes from," said Haacke.

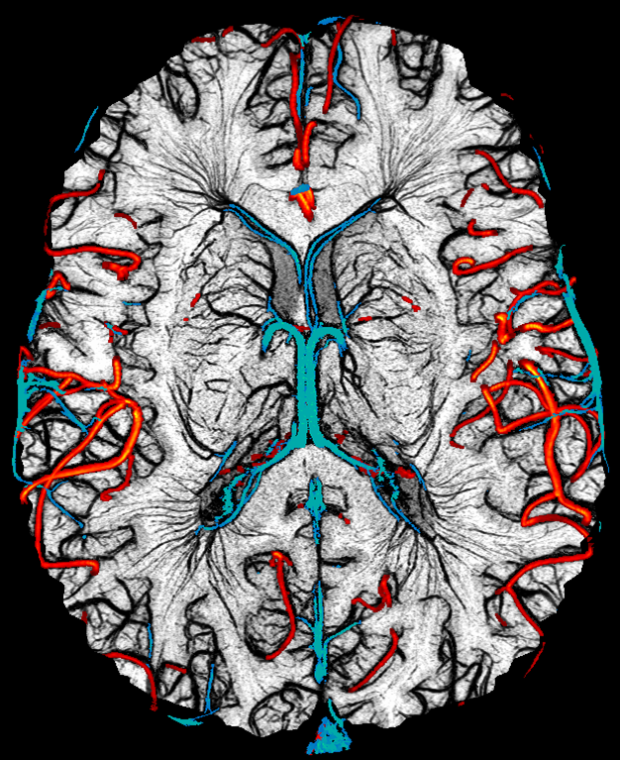

The physicist and his team have developed some increasingly detailed and striking images showing blood flow in and blood flow out and hopes to use the new way of visualizing blood flow to learn more about what’s going on upstream in the brain.

The question really is "if there are flow obstructions, where are they taking place?"

(Mark Haacke and Yulin Ge of New York University have developed a new technique they refer to as microimaging to map out all the vessels (both arteries and veins) in the human brain down to 50 to 100 microns in size. In these images, one can see the major arteries marked in red, the major veins in blue and then the smaller vessels. These images were produced by Dr. Sagar Buch from Ontario, who collaborates with Haacke in Detroit.)

Other scientists are taking Zamboni's template and investigating flow problems in diseases such as headaches and Meniere’s disease, a disorder of the inner ear that can cause vertigo and hearing loss.

Scientists at the meeting reported that they found impaired jugular veins in about 80 per cent of those with Meniere’s compared to about 11 per cent of healthy patients who were also studied. When treated with angioplasty, the researchers reported improvements.

"The main symptom -- vertigo -- was reduced in 75 to 80 per cent. Many reported hearing better," said Dr. Aldo Bruno, a vascular doctor from the University of Bologna.

Spurred on by Zamboni’s work, researchers in China are also now investigating the effects of abnormal outflow from the jugular veins and its link to neurological diseases.

There appears to be a rebranding of the concept- as they focus on internal jugular vein stenosis (IJVS) with no mention of controversial term CCSVI. They report that, in patients with poor blood outflow, there are formation of brain lesions.

And some are calling for more study.

"Discussion on every aspect of this newly recognized disease entity is in the infant stage and efforts with more rigorous designed, randomized controlled studies in attempt to identify the pathophysiology, diagnostic criteria, and effective approaches to its treatment will provide a profound insight into this issue," says Dr. Da Zhouof the Department of Neurology at Capital Medical University in Beijing.

SUPPORTERS UNDETERRED

Most scientific meetings are filled with researchers. What's unusual about the ISNVD meetings is the contingent of patients who travel the world, on their own dime, to attend.

Most of them have multiple sclerosis. Many were treated with angioplasty. And all remain convinced there is something to Zamboni's work.

Ottawa native Florence d'Eon walked down the streets of Ferrara showing no obvious sign that she has lived with MS for much of her life.

D’Eon, 68, said she used to feel "sick all the time with brain fog." She even considered suicide. "There was nothing I could do to make myself feel better," she said.

Because the angioplasty for MS was not available in Canada, d'Eon had the procedure at a clinic in Bulgaria. A few hours afterwards, she said, "the brain fog lifted and it's never come back."

(Florence d'Eon of Ottawa, Ont., speaks to CTV News)

Since then, d'Eon has travelled to eight ISNVD meetings including one in China – something that she says would have been impossible for her before the treatment.

"I think history will prove CCSVI was correct and I was there at the start. If I am wrong about this, I need to be institutionalized," she said with a smile

Others like Carol Schumacher are betting that, with funding and time, science will eventually explain what is going on in the brain. Schumacher had angioplasty twice for her MS. "I'm certainly not cured," she said. "I still have my limp and wobbly walk. But I got better."

Schumacher is now a director with the Annette Funicello Foundation, established by the Hollywood star after she was diagnosed with the disease. Each year, the foundation awards research grants to young scientists in the field.

"I feel it is following the way of new disruptive ideas... You get trashed, you go underground and you emerge again," she said, adding: "The science always wins in the end."

NO REGRETS?

Paolo Zamboni full well knows science can be difficult and messy and describes the past decade as "very demanding and difficult."

On the 10th anniversary of the publication of his key study, he is in New York presenting a new paper and remains among those still trying to understand why there were such varied results using angioplasty.

And his team says it has identified a sub-group of patients in last year's Brave Dreams trial with particular categories of vein abnormalities.

When they analyzed how patients did after angioplasty, based on the type of vein narrowing, they were able to see a pattern suggesting which patients would do well after the procedure. These "responders" had better blood outflow and fewer new brain lesions after one year.

"It shows that careful patient selection is essential," said Sclafani, who was part of the study.

"In other words, this study stimulates by asking new questions" he said.

Despite all the controversy, Zamboni's career as a vascular specialist hasn't suffered. He heads the Vascular Diseases Centre at the University of Ferrara. He also collaborated with NASA to measure blood flow out of the brain in outer space.

His wife Elena, who was among the first to be treated, also attended the May meeting -- healthy and still supportive of her husband's work.

The fact Zamboni is still studying brain blood flow and neurologicial diseases will no doubt frustrate many of those who have considered the CCSVI saga.

It will also hearten others who are still intrigued by his controversial work.

"This kind of research is opening doors, in my opinion, for neuro- degenerative disorders," he said.