B.C.'s chief coroner and the province's top doctor are issuing the latest in a series of warnings about the overdose crisis, as figures show the number of overdose deaths stands at 755, which is more than 70 per cent higher than this time last year.

November saw a deadly record broken, with 128 people dying from drug use beating the record of 82 set in January.

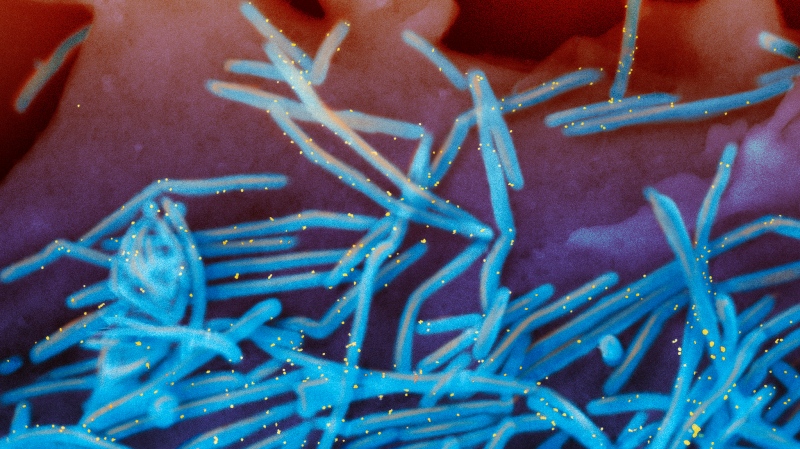

Roughly 60 per cent of this year's deaths, amounting to 374, were related to the deadly opioid fentanyl. That is a 194 per cent increase from the same period in 2015.

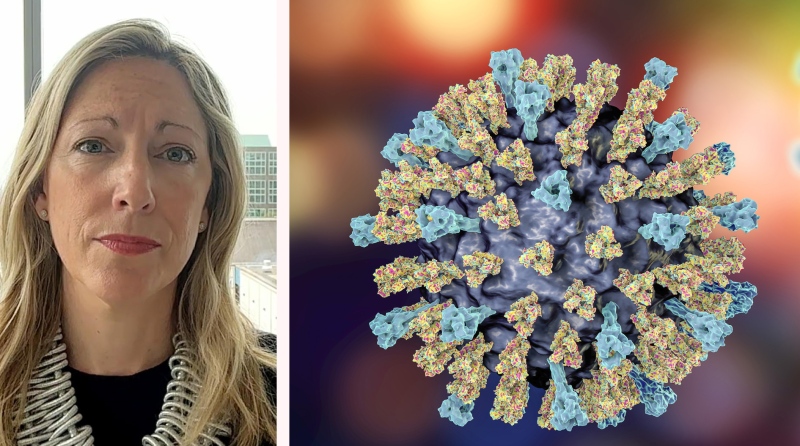

"The number of deaths we're seeing is heartbreaking," Lisa Lapointe, the province's chief coroner, told a press conference today.

Vancouver leads the way in cities tracking fentanyl-related overdose deaths, with 67 people dying this past year.

Despite setting a record in November for deaths, Lapointe is concerned that December could be even worse.

The number of deaths has appeared to be particularly centred in Vancouver's Downtown Eastside neighbourhood, where police have issued several warnings in the wake of deaths.

Six people died from overdoses in the neighbourhood last Friday.

The sheer number of overdoses in the Downtown Eastside prompted a series of pop-up safe injection sites organized by community activists Sarah Blyth and Ann Livingston.

The Overdose Prevention Society has been organizing pop-up safe drug injection and consumption sites since September, with volunteers trained to administer naloxone, a drug that counter react the effects of opioid overdoses, and offer CPR.

The province has since announced that overdose-prevention sites will open in Vancouver, Victoria, Surrey and Prince George where users can take drugs while being monitored by staff trained to use naloxone.

However, Lapointe says it's important to note that the overdoses are affecting people across social classes.

"It affects all walks of life – teachers, doctors, university professors, students. People think they're immune because they are not in the Downtown Eastside, but that's just not true," she said.

One family on Vancouver's affluent West Side says their son's death illustrates that point.

Jack Simpson, 18, died last March after taking OxyContin laced with fentanyl.

"Kissing your son goodbye in a body bag is something that no human being should have to do," said Simpson's mother Stacey Dallyn.

Dallyn notes that her son was in the gifted program at school and doesn't fit the stereotype of a drug user.

"This is Russian roulette, and there's a bullet ready they don't see coming," she said, adding that parents need to talk to their kids without judging their behaviour.

Dallyn, along with Vancouver police and firefighters, is calling for more treatment beds, but B.C.'s top doctor says more beds aren't a complete solution.

British Columbia's premier has promised to add 500 beds by early next year to be available for treatment, but only 200 have been made available so far.

"Beds are part of the solution, but it's what happens in those beds, before that bed, and what happens after you get out of that bed, in terms of support," said Dr. Perry Kendall, B.C.'s provincial health officer.

Kendall says an increase in prescribing opioid substitutes could help slow the death rate.

The overdose crisis led to Vancouver's city council approving a budget last week that includes a 0.5-per-cent increase in property taxes to support frontline workers who are responding to overdoses.

With a report from CTV Vancouver's Bhinder Sajan