Francine Brunet and her daughter Josee sit comfortably beside a fireplace in the Dorothy Ley hospice in Etobicoke, Ont. Volunteers are making muffins and soup nearby.

“When we arrived here, and when I saw it, I said ‘Thank god, thank god’!” Josee said.

“This is what dying should look like,” they told us.

Francine has end-stage lung cancer that has spread to the liver. Josee could no longer care for her mother at home and applied for a room at the hospice. She’s been in care suite No. 9 for a week.

Volunteers make special meals and play beautiful music. Francine’s room has a bright window and a vibrant handmade quilt hangs on the wall beside her family photos. Francine’s every need is attended to -- all with a simple ring of a bell.

“They ask, ‘what would you like for dinner?’” says Josee with a smile. All her mother’s medical needs are tended to by palliative care doctors and nurses. Francine had told them: “I don’t want any pain.”

It’s a stark difference, they say, to the recent death of Francine's husband from a brain tumour. He died in a hospital. The family says it was harsh and impersonal. “No, he didn’t have palliative care” says Josee. “If he had this, it would have been beautiful,” says Francine.

The goal of the hospice and palliative care is to minimize the suffering of the patients and their families and to make the best of their last days. The average stay here is 21 days, though some patients have stayed longer.

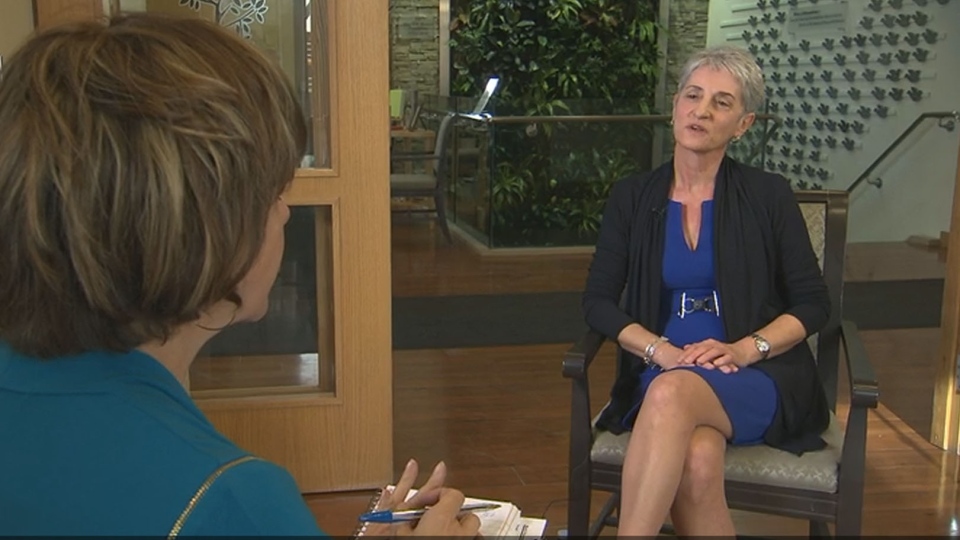

Zaynep Onen, vice-president of the Dorothy Ley Hospice in Mississauga, says staff talk to people and ask what they want to accomplish in this period.

“What do you want your end of life to be?” Onen says they ask. “Things you haven’t done yet, people you want to talk to, conversations you haven’t had. A hospice asks: ‘What is it you want?’ We talk to the individual and ask them: ‘What do you want to accomplish in this period?’”

For one client, it was a wish to ride on a pontoon boat. And the volunteers arranged that.

The Dorothy Ley Hospice provides palliative care for about 180 people in its residence each year, and delivers palliative care at home to some 2,300 others in western the western Toronto area.

A report by the Canadian Cancer Society says half of those with terminal illnesses never get this high quality end-of-life care.

Gabriel Miller, a co-author of the Canadian Cancer Society report, says one in two cancer deaths are happening in emergency or acute care hospitals. “These are people who largely would prefer to be treated in the home or community,” Miller says.

Studies show:

- palliative care at home or in a hospice costs up to a third less than hospital care

- patients who consulted with a palliative care team within two days of hospitalization had an up to 32 per cent reduction in subsequent hospital-health care costs, compared to patients not given palliative consultation

- palliative care may decrease unwanted aggressive end of life care as well as shorten length of stay in hospitals.

According to the Hospice Palliative Care Ontario Association, in 2014/2015 alone, residential hospices saved the Ontario health care system a minimum of $23 million because hospitals were able to admit patients to a hospice when it was evident they didn’t need acute care in a hospital.

The report says that as Canada and the provinces prepare to offer the sick and dying a doctor-assisted death, they should also guarantee expanded palliative care.

“You can't do one without the other,” Miller said. “It would be unfair to Canadians and irresponsible."

Susan Ling is now a convert to the idea. She says she didn’t know much about hospice or palliative care, until her mother, Ester, was dying of pancreatic cancer. No longer able to care for her at home, she brought her to the hospice.

In her last month there, hospice volunteers helped bring in Susan’s father, who is also ill, to visit his wife, and helped the family celebrate Ester’s last days. She died Saturday.

“I am grateful from the bottom of my heart,” Ling said. “It gave my family a great sense of comfort.”

The Dorothy Ley is supported by 340 volunteers who cook, visit with the residents, handle reception and visitors. And about 60 per cent of its budget comes from the provincially-funded local health network. The rest of the budget comes from donations.

“It would be so great to have more sustainable funding,” Onen says.

The federal government has promised some $3 billion over four years to expand out-of-hospital and home care, and advocates are hoping some of it will go to improving access to palliative care.

As well, advocates hope the issue is discussed at a meeting of health ministers in Vancouver later in January.

---