Ever notice how the older you get, the more you have learned to embrace the morning? Or how the seniors in your life are always the first ones up at the crack of dawn?

New research has found there’s a reason for that. Psychiatry researchers in the U.S. have found that the circadian rhythm of our gene activity changes with age.

We all have 24-hour internal clock genes, or circadian rhythm genes, controlling nearly all our brain and body processes, such as our sleep and wake cycle, our alertness and our metabolism.

These genes tell our bodies to release the hormone melatonin to make us sleepy at night, for example, and to warm up our body right before we wake in the morning.

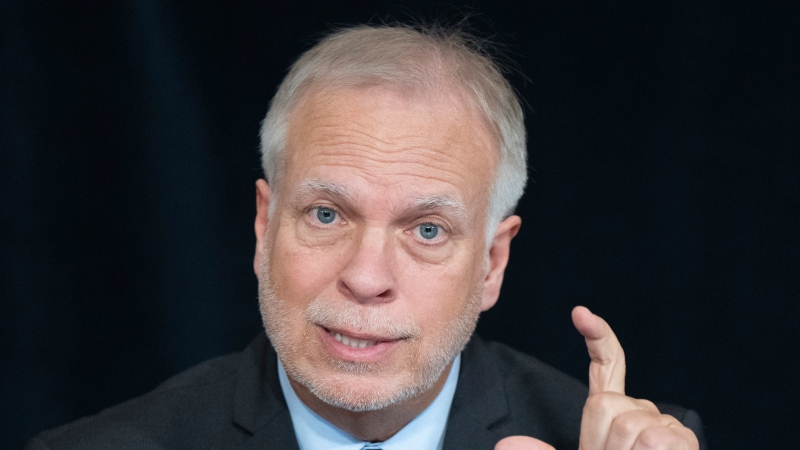

Senior investigator Colleen McClung says these rhythms change with aging, leading to the need for fewer hours of sleep, a tendency to awaken earlier in the morning, and “less robust” body temperature rhythms.

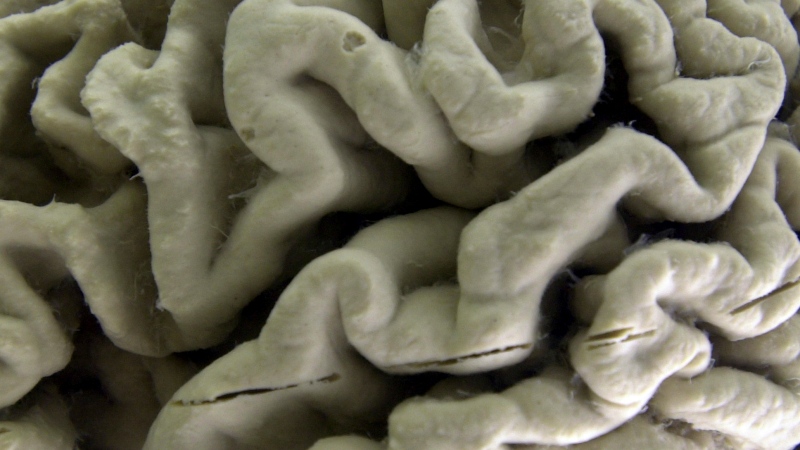

McClung, an associate professor of psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, and her team wanted to look at the effects of aging on molecular rhythms in genes found in the prefrontal cortex, an area of the brain involved in learning, memory and more.

The team examined brain samples from 146 people whose families had donated their remains for medical research.

They divided the samples by age and looked for rhythmic activity, or expression, of thousands of genes in the samples. What they found was that, in older brains, there was a loss of rhythmic activity in a number of core clock genes.

McClung said that might explain why our sleep changes later in life.

Interestingly, the team also found a set of genes that actually gained rhythmicity in older brains.

This information, the team says, could ultimately be useful in the development of treatments for cognitive and sleep problems that can occur with aging. It might also lead to a treatment for “sundowning,” a phenomenon in which seniors with dementia become confused and anxious in the evening.

The researchers next want to explore the function of the brain’s circadian-rhythm genes in lab and animal models. They also want to see if these genes have been altered in people with psychiatric or neurological illnesses.

The full study appears in PNAS, the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.