Suffering through a bout of food poisoning is an unpleasant but typically short-term aspect of life for anyone who’s ever eaten a contaminated meal, but Canadian researchers have released new findings that show there can be long-term effects for those at-risk for Crohn’s disease.

Researchers at McMaster University in Hamilton, Ont. found that exposure to food-borne pathogens that cause acute infectious gastroenteritis, more commonly known as food poisoning, may “accelerate” the growth of a bacterium that has been linked to the debilitating inflammatory bowel disease.

The study was published in the medical journal PLOS Pathogens earlier this month.

For the study, the research team exposed mice already “colonized” with adherent-invasive Escherichia coli (AIEC), a bacterium that has been associated with Crohn’s, to bacteria Salmonella Typhimurium or Citrobacter rodentium, both of which cause gastrointestinal disease.

Senior study author and McMaster University professor Dr. Brian Coombes said in an interview with CTVNews.ca that the results of the study indicated that the food-borne disease could “create an environment” in the gut in which the Crohn’s-associated bacteria can grow, leading to the onset of Crohn’s even years after a person has recovered from a bout of food poisoning.

“You set up this situation where the pathogen comes in via contaminated food or water, inflammation gets generated, and if that particular host has these Crohn’s-associated E.coli already in them, then you’ve created an environment within the gut that allows them to thrive and grow to very, very high numbers,” he said.

Dr. Coombes and his team at the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research have been studying how microbes affect Crohn's, but he says it's what actually causes the intestinal disease that is still a mystery in the medical world. Crohn’s and ulcerative colitis affect one in every 150 Canadians.

"The pathway to get to Crohn’s is really an enigma,” he said. “People don’t really understand in a fulsome way, what generates Crohn’s disease. There are lots of risk factors that I would say are very well-known in the literature.”

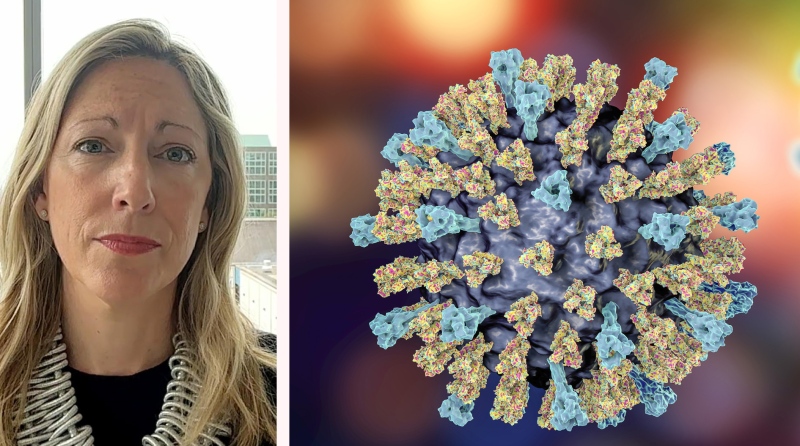

Aida Fernandes, vice-president of Research and Patient Programs at Crohn's and Colitis Canada, says relatively recent research into Crohn’s has indicated that a combination of genetics, environment as well as microbiology can influence a person’s risk for developing the disease.

“We know it’s not just a single factor. You don’t just inherit this disease,” Fernandes said in an interview with CTVNews.ca. “There is a genetic component, but understanding what your susceptibilities are, that somehow a combination of your genes, the environment in which you live, the microbes that live in your gut, all seem to kind of have an interaction and certainly at the end of the day play a role” in possibly leading to the development of Crohn’s.

Dr. Coombes says it’s well-known that microbes are the “key driver” of Crohn’s disease.

“The next question that really is the holy grail to be solved is, what are the bacteria?” he said. “Which ones are there? There’s trillions and trillions of bacteria in our gut – which ones are the real bad guys that are causing this kind of Crohn’s associated inflammation."

“We think these (adherent-invasive Escherichia coli) are one of the bad guys,” he added.

Dr. Coombes said his research team was "inspired" by previous human studies that have tracked the link between food poisoning and Crohn's.

He said of a previous study, that the "really striking finding is that if you’ve been exposed to food poisoning even once, your risk of developing Crohn’s disease within the next 15-year period is significantly higher than if you were not exposed to food-poisoning."

Such a large gap between the food poisoning and the onset of Crohn's, Dr. Coombes said, provides an opportunity to "intervene if an intervention is available."

The hope is that their findings will prompt the development of treatment to intervene following a bout of food poisoning.

"Based on what we have found in this paper, I think that one useful thing can be to identify individuals after they’ve been exposed to food poisoning, think of a way to try and identify those individuals which also harbour these AIECs because they might be at a greater risk later on," Dr. Coombes said.

Fernandes called the study’s findings "very exciting,” and “important new information that hopefully will continue to shape” new research and therapies.

"If you know in advance who might be more at risk of developing the disease, might you try to intervene in a much more proactive way,” Fernandes said. “So just the more we know about what causes the disease, the better position we’re in to try to find better treatments or ultimately, cures for the disease.”