When Allison Kooijman learned that an advanced cancer her doctors diagnosed her with was not spreading at all, she didn’t celebrate. Instead, she sank into a deep depression.

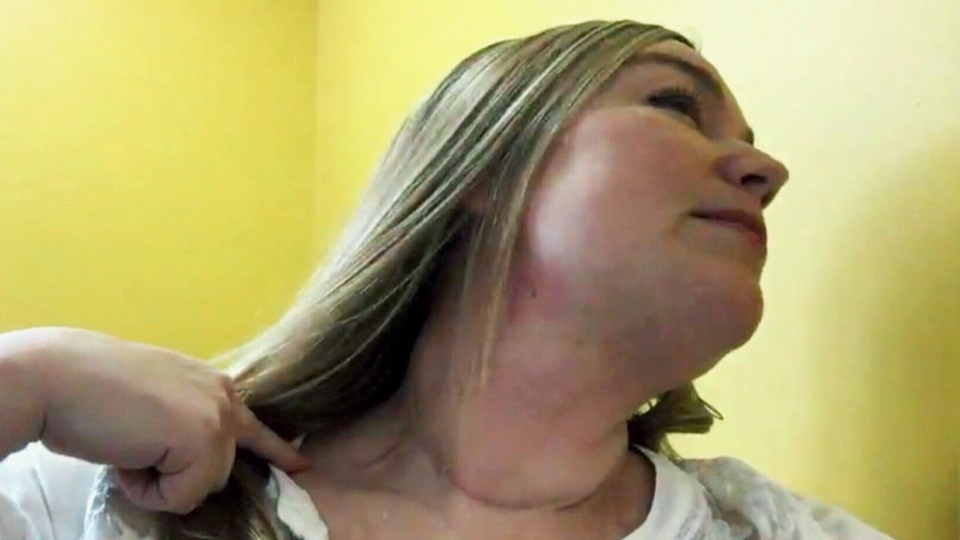

The Vernon, B.C. woman had undergone extensive surgery to remove 30 lymph nodes from her neck to try to arrest the thyroid cancer. But it turned out that most of those nodes didn’t need to come out at all, as tests after her surgery showed they were all perfectly healthy.

“I was literally cut ear from ear, all the way across the bottom of my neck,” Kooijman told CTV News, tracing her scar line with her finger.

Doctors apologized for getting it wrong, but by then, the damage had been done. The surgery had damaged a nerve in her upper back, leaving her unable to return to work as a licensed nurse.

“It was a career that I really loved. I felt I was contributing and I had a really meaningful existence. To not be able to return, this has been quite an identity crisis. It has been life-altering,” she said.

Though her doctors were caring and apologized, when Kooijman wanted to learn more about the hospital’s investigation into the errors made in her case, she was shut out. No one would return her calls nor give her any answers.

Her frustration with hospital administration, combined with her grief over her lost career and stress from her misdiagnosis all caught up with her.

“I went through massive depression, even to the point where I was suicidal, just because of the impact that it’s had on my life and then on my psyche to be kind of pushed away,” she said.

Now, psychologists say there’s a term to describe what Kooijman experienced: “institutional betrayal.”

It’s the feeling that an institution in which someone has put their trust has betrayed them by failing to respond to a negative event, thereby worsening the victim’s trauma or pain.

Bridget Klest is a University of Regina psychology professor who has been researching the phenomenon. She says, when hospitals or institutions deny a mistake or try to cover it up, often in a bid to protect their reputation, it leads to intense pain for the victims involved.

“Institutional betrayal in the medical system really resonates with people. When they hear about it, they say, ‘Yes, that’s my experience. That’s me,’” she says.

Klest and her team are hoping to learn more about how often this form of betrayal happens, why it happens, and what can be done to avoid it. The first step, she says, is to acknowledge it all.

“(We’ve had) confidential conversations with people who are in the medical system - doctors and nurses – and they have themselves said this is a huge problem.”

University of Oregon psychology professor Jennifer Freyd helped to coin the term “institutional betrayal” and has written extensively about it in other contexts, such as in cases of sexual harassment or assault when supervisors or authorities fail to take action.

She says health-care organizations need to recognize that medical errors do happen. They also need to avoid contributing to patient suffering by taking responsibility when things go wrong, apologizing, and looking for ways to prevent such errors in the future.

Klest and her team are about to begin a new study and are seeking pregnant women in their third trimester to document their in-hospital births.

As for Kooijman, she says she eventually got an apology from the hospital involved. But she’s hoping the research underway in Regina will help make the health care system safer and kinder to patients who follow.

Kooijman is now trying to improve the system. She works as an advocate for the Patient Voices Network, and recently became a director on the Canadian Justice Review Board, where she will work to help the victims of medical errors.

Kooijman has also proposed the creation of a “healthcare compensation board” to deal with complaints in a more humane way.

With a report from CTV medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip