LONDON -- As a child, I remember living in fear of getting polio.

I’m not sure when I got a polio vaccine—I was certainly very young—but by then, we all knew somebody with spindly, diseased legs trussed up in heavy metal braces.

You didn’t want to be that person.

With polio, it seemed like a matter of fate. You either got it, or you didn’t. No amount of hand washing would make a difference.

I watched with fascination as the Smith family down the street built a ramp into their house for their disabled son David. I was whole. He was stricken for life.

The vaccine felt like a miracle, or a magic potion. You didn’t have to worry anymore about ending up in a wheelchair, which in a small village was more or less a death sentence.

If you couldn’t walk, then what was left?

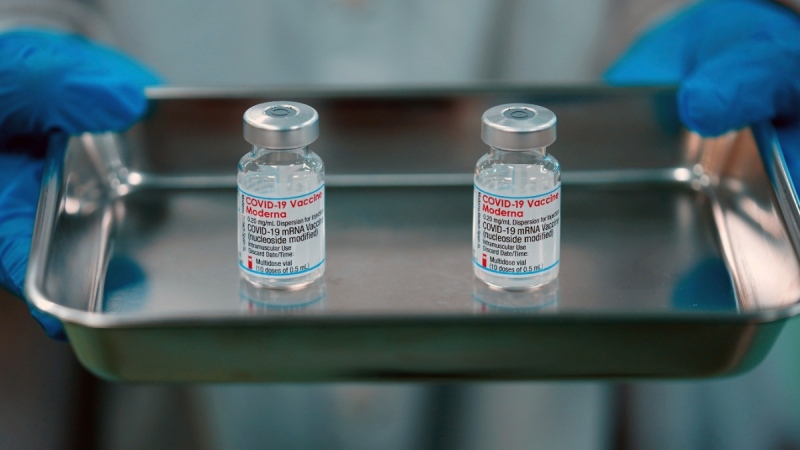

All these decades later, it is both fascinating and disturbing to be living through the same childhood fear of death and disease, as the world waits obsessively for another magic potion.

Behind the lockdowns and the social-distancing and the mask-wearing, there has always been the tantalizing prospect that if we did our best to stay safe now, if we made a small personal sacrifice, science would step in with a needle and deliverance would be ours.

A shot in the arm. A jab. A booster. Patience.

There isn’t much patience when you’re trapped in a care home and haven’t been able to hug your loved ones for months. It’s a lonely, miserable torture.

Just as a vaccine offers a lovely end to that torture.

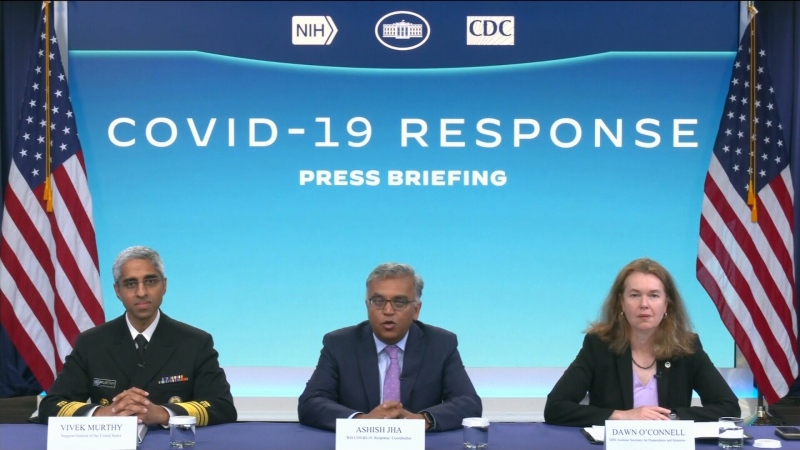

Are we to applaud science for its brilliant work—of course we are—but these are the same scientists who warned it could take years to develop a vaccine, if ever.

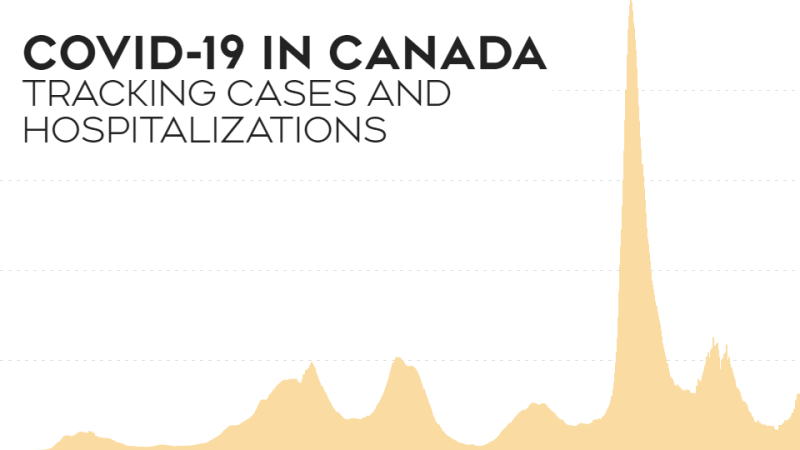

Hope rose and fell with each new headline.

Now there are four potential vaccines showing immunity levels at 90 per cent and above. At one point, the scientific world would have been happy with 50 per cent.

In the U.K., it might be a retired doctor who gives you the jab, or a firefighter. The country is ramping up for mass inoculation. Let’s hope it goes better than eight months of confusing, ever-changing lockdown guidelines.

The residents and staff of the country’s 15,000 care homes will get priority. It is a considerable moment, especially for caregivers who often feel invisible or overlooked.

“It’s like the role is reversed,” said the manager of a care home in Sutton. “We have felt abandoned and now we’re in the forefront.”

And it’s altogether possible this could start by Christmas.