TORONTO -- Though all eyes are on a potential COVID-19 vaccine, experts still warn that the pandemic could worsen before most Canadians are inoculated.

The continued alarm bells, which health officials have been ringing for months, are based off pandemic modelling done by epidemiologists at the Public Health Agency of Canada, who use a mathematical growth model to formulate their projections.

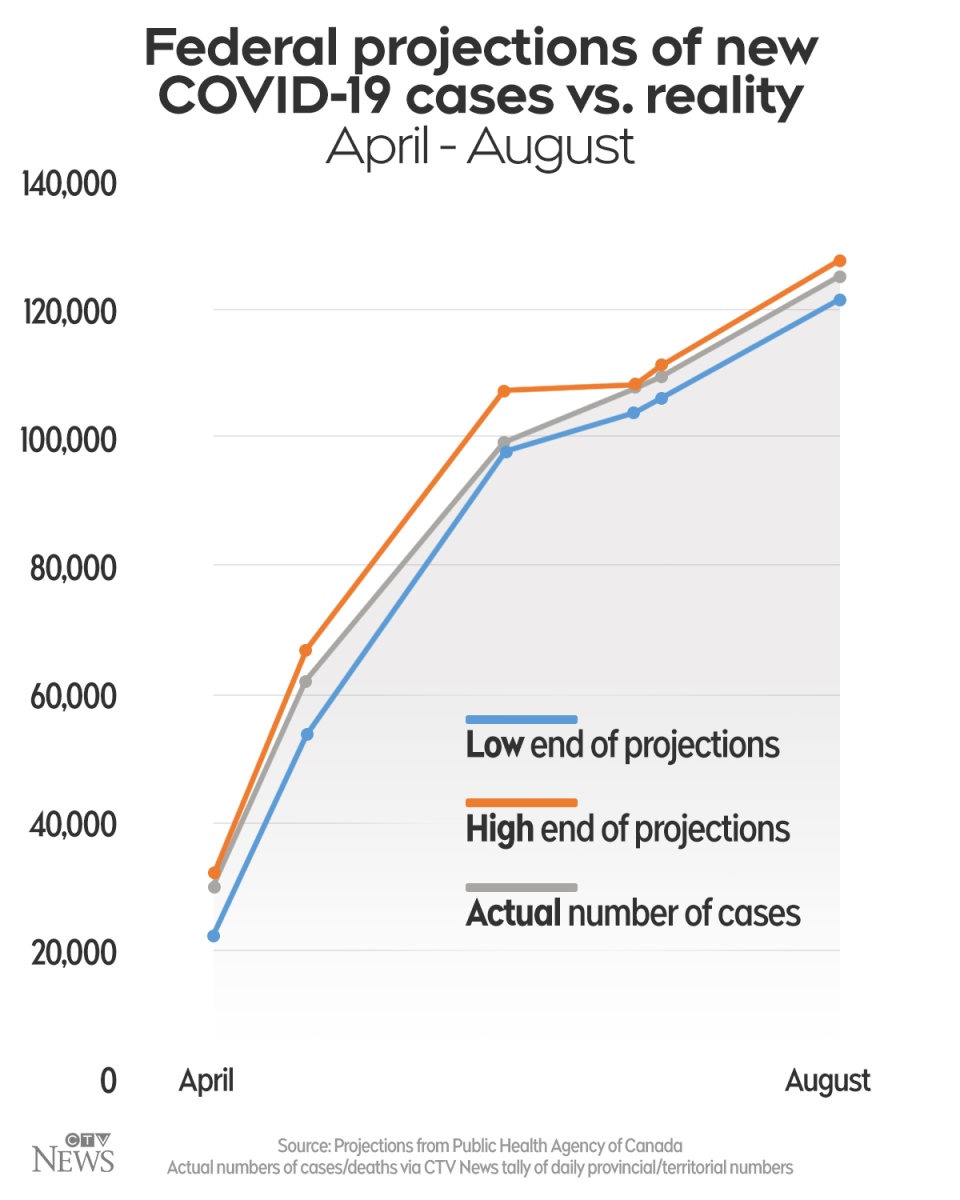

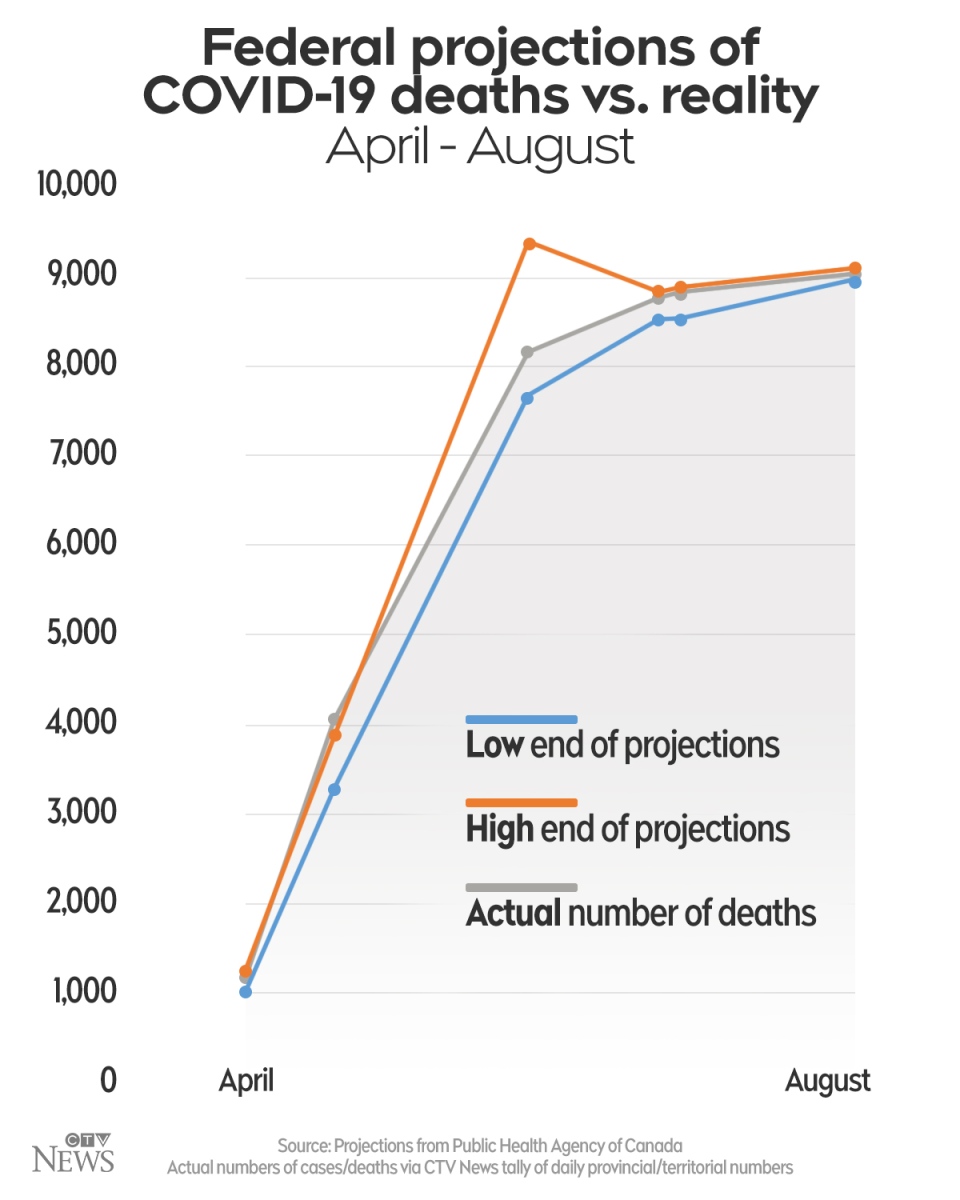

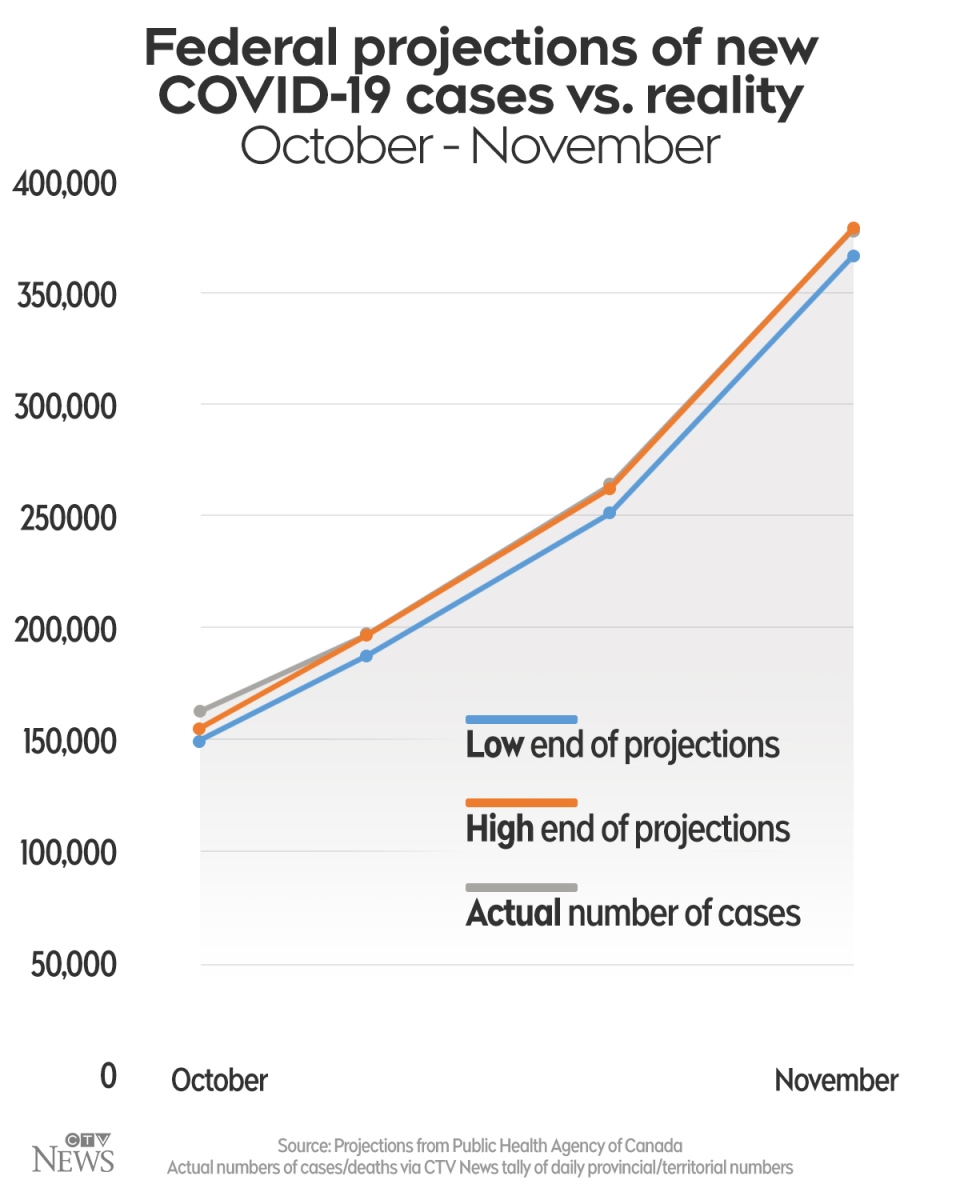

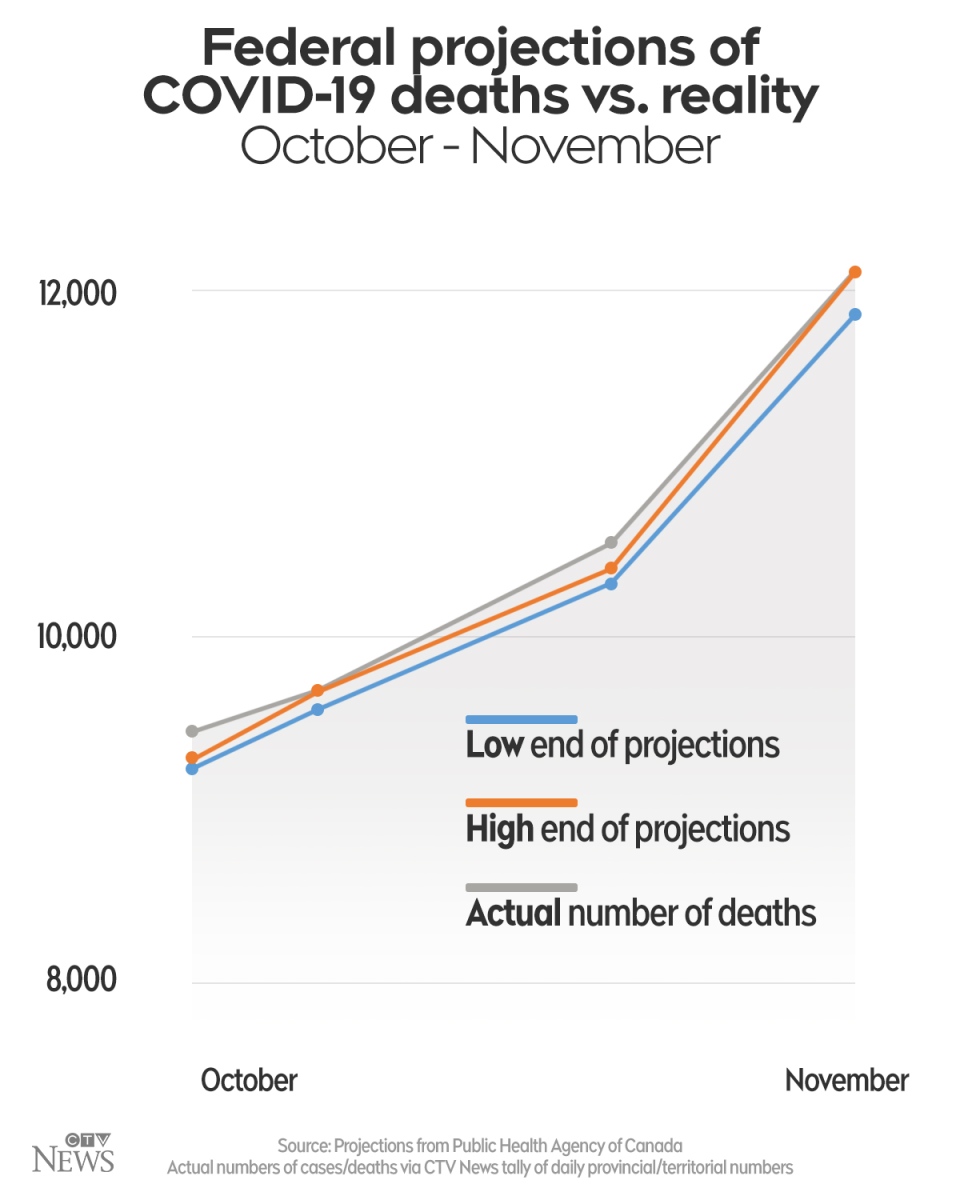

Ten times since April, the federal government has released epidemiological updates on the state of the pandemic. Each update included a short-term forecast of the infection trajectory in the country. More recently, there have also been longer-term predictions. CTVNews.ca pulled the numbers to see how the projections compared to the reality on the day in question.

Almost all of the estimates have turned out to be accurate, most often on the higher end of the projected range. Lately, the projections have hinted at a grim course for the pandemic, the Public Health Agency of Canada said in a statement Monday.

"[I]n recent weeks the actual numbers have been greater than the projected numbers, and this indicates that the epidemic is accelerating," an agency spokesperson wrote in an email to CTVNews.ca.

"Now, more than ever, everyone needs to keep up with public health practices—including physical distancing, handwashing and wearing masks—to reduce their risk of being infected and to reduce the risk of spreading the virus to others."

In early October and early November, as the second wave of COVID-19 intensified, the projections turned out to be lowballing the course of the pandemic by several thousand cases. Death projections missed the mark four times, first in May and most recently at the end of November. Only in June, as the first wave of the pandemic dropped to a seven-day average of fewer than 800 new cases, were the projections on the lower end of the estimated window.

While the government has stuck to shorter-term projections, it began making longer-term estimates in the fall. In late September, PHAC estimated Canada could exceed 3,000 new infections each day by mid-October. That estimate didn’t play out. By mid-October, health officials logged below 2,500 cases most days,with a seven-day average of about 2,300. Similarly, the agency said cases could exceed 5,000 a day by November,but officials recorded a seven-day average around 3,000 in early November.

Those longer-term forecasts were based on Canadians keeping the same rate of contacts. The agency also provided two other predictions: one in which contacts increased by 20 per cent, and one in which they decreased by 25 per cent. The pandemic has neither spiked or waned in the way projected by those forecasts.

But the long-term estimate for December proved most accurate. On Oct. 30, PHAC estimated that the country could exceed 6,000 daily cases by early December if Canadians maintained their level of contacts. So far this month, officials have recorded more than 6,200 new infections every day,with the exception of Dec. 1 when the country logged 5,330 new cases.

This month, PHAC estimated that Canada could exceed 15,000 reported infections daily by mid-December and 20,000 by the end of the month when people typically gather for the holiday season. In recent days, officials have emphatically discouraged people from gathering with anyone outside their own household for Christmas or other celebrations.

The projections go hand-in-hand with public health advice such as lockdowns and physical distancing, because they aren’t weather forecasts, says Ashleigh Tuite, an epidemiologist at the University of Toronto's Dalla Lana School of Public Health. Canadians can affect the pandemic currents.

HUMAN BEHAVIOUR IS THE ‘X’ FACTOR

“If the weather forecast is for rain, that forecast doesn’t change if you take an umbrella with you,” Tuite told CTVNews.ca over the phone earlier this month. “But for infectious diseases, if I tell you that there is going to be a large increase in cases, and you take that information and change your behaviour -- you decide not to leave the house, or when you leave the house, you take your mask with you -- that actually affects the future.”

While the shorter-term forecasts are less likely to miss the mark, said Tuite, it’s a good thing when projections are wrong, especially in a pandemic when the caseload reality is lower than the prediction.

“That suggests that human behaviour or something else has changed that forecast or potential future,” said Tuite.

Human behaviour is the “X factor,” the piece of the equation that is unknown or unforeseeable, she added, making longer-term projections a particular challenge. Human behaviour won’t have much impact on shorter-term projections that fall within a two-week range or less, because public health interventions typically take at least two weeks to affect the epidemic curve, she said.

- You can now sign up to CTV News' Nightly Briefing newsletter, our evening reading recommendation. You can sign up here to receive it each weekday night.

That means that even the 20,000 cases per day projected for the end of December may not be the maximum. If holiday gatherings occur, despite authorities' warnings against them, it will be well into January before infections passed on at those events make their presence felt in the daily totals. On the other hand, if Canadians cut down on their contacts, the situation could rapidly improve.

"We have the ability to change our future, and models are part of that to help people understand where we’re headed and how we can change," said Tuite. "They’re not inevitable."

Human behaviour is simply challenging to predict, particularly in such unprecedented times.

“People’s attitudes and risk aversion [have]changed over time,” she said, noting that she couldn’t have predicted in March or April how a sense of “COVID fatigue” would have played into adherence to health protocols. “Those are all things that are going to be captured in terms of the disease dynamic and in terms of the number of cases that we see, but trying to predict that or anticipate that can be really hard.”

Edited by CTVNews.ca's Ryan Flanagan