TORONTO -- Social isolation, school closures, and restricted access to sports and recreational activities have all taken their toll on children's mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to Children's Healthcare Canada, there has been a 200 per cent increase in hospital admissions for substance use disorders and a 100 per cent increase in suicide attempt admissions compared to the year before.

Canada's Children's Hospital Foundations has reported that 70 per cent of those between the ages of six and 18 said the pandemic has harmed their mental health in at least one area, such as anxiety or attention span.

"When kids are confined at home for weeks, sometimes months on end, cut off from their peers, cut off from physical activity, they're going to languish," Sara Austin, the CEO of Children First Canada, a national charity that advocates for the well-being of children, told CTV's Your Morning on Thursday.

"This is deeply worrying."

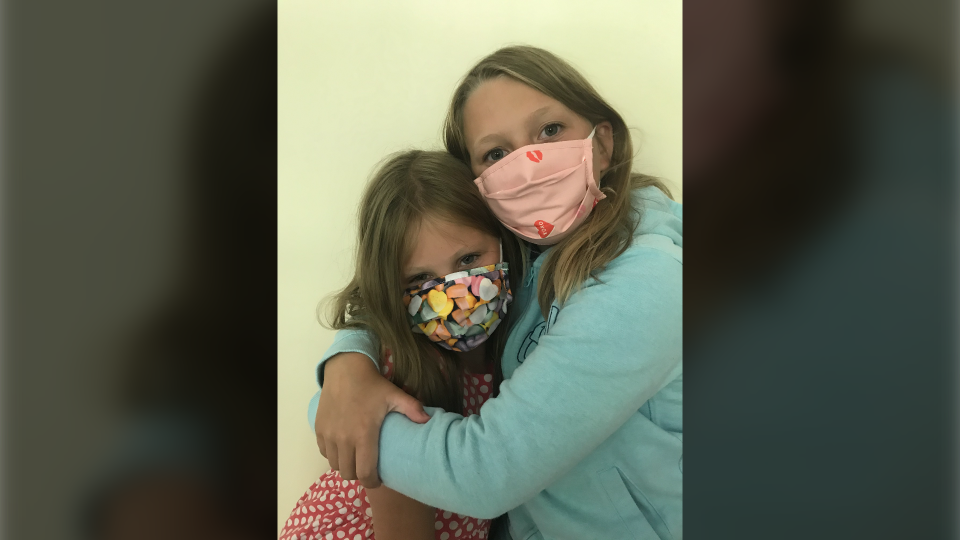

Stephanie Mitton, too, is seriously concerned about the well-being of her two daughters Rachelle, 10, and Renee, 7, during the pandemic.

Her older daughter has struggled with her mental health from being in and out of school and being unable to see her friends because they're in a different class.

"Most of her friends are in another Grade 4 class so she could go like months and never see them because you're not allowed to see your friends outside of school, you're not allowed near other classes on the playground," Mitton, who works part-time as a government relations adviser for Children First Canada, told CTVNews.ca on Thursday.

"When they went back [to school] in September, she came home every day crying for a month."

Mitton said her daughter described her return to school with the new public health restrictions in place as being "like jail."

"Like when you eat, you have to look forward, you can't go close to other kids, if somebody dropped something on the floor, you're not allowed to pick it up," she said.

"I want my kid to be safe and if the measures need to be in place for public health, then I'm supportive of them, but I don't think there's enough recognition of how hard it is from the child's perspective."

Megane Jacques, the vice-chair of Children First Canada’s Youth Advisory Council, said the past year of virtual schooling has been difficult for her too. Starting a new program at a new college, Jacques said it was quite hard for her because she couldn’t meet her classmates and teachers in person.

“I never really got to experience what college is because it was all at home,” she told CTVNews.ca during a telephone interview from her home in Trois-Rivieres, Que. on Thursday. “We lost access to our support system, not being able to have access to the social workers at school, being able to have teachers look out for us, not being able to reach out to each other and make new friends… all those coping methods that we used to have weren't available to us anymore because of the pandemic.”

In fact, Jacques said that a quarter of the students in her class dropped out by the second semester.

“That's a lot of people,” she said. “Most of them were also really good students that cared about education, but it was so hard being at home and not having access to everyone that, honestly, it was just not doable.”

Jacques, who has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), says remote learning has been so challenging she expects to complete her two-year program in three years instead.

Mitton’s younger daughter has also been struggling academically as a result of the pandemic. She said if her daughter doesn't understand a lesson during her virtual classes, she'll just sit there and not understand.

"The teachers will ask her to show them her work and she just won't because she didn't do it because she doesn't understand. So that's been heartbreaking," she said. "I have to sit beside Renee when she does her schoolwork, or literally, she'll sit there for hours and not understand anything."

While Mitton said she's been fortunate to access some additional support for her older daughter through her school, she's had to turn to a private clinic to assess her younger daughter's learning abilities because the wait for the school program was two years.

"Two years! That means two years of her not understanding her schoolwork, completely falling behind, basically not learning to read," she said.

From her own experiences at home and her work with Children First Canada, Mitton said she's supporting the #codePINK campaign, which aims to draw attention to the mental health crisis affecting children during the pandemic.

#codePINK

Launched by Children First Canada, with the support of Canada's top children's hospitals and advocacy organizations, the #codePink campaign takes its name from the term doctors use to declare a pediatric emergency.

The campaign is calling for an urgent meeting of Canada's first ministers to take action to ensure that children receive immediate and sustained support for their mental and physical health.

"Code pink references a pediatric emergency. In a hospital setting, that means people stop what they're doing and they come urgently to the rescue. And that's what we're asking of our leaders right now," Austin said.

The CEO of Children First Canada said the charity and their partners are calling on the prime minister and every premier in Canada to hold a first ministers meeting to discuss the crisis affecting children and put together a plan of action to address it.

"We want to see kids safely returned to school as quickly as possible. The reopening of parks and sports programs, camps for the summer, and we need a plan now to ensure that kids can safely return to school in the fall," Austin said.

In addition to reopening these things, she said they're also calling for large investments in the mental and physical healthcare for children to address the "enormous" backlogs that are currently in place to ensure they have access to life-saving care and treatment.

"We simply haven't seen that robust investments that are really needed in our health-care system, particularly when it comes to the mental health of our children, but even simple things like accessing rehabilitation services or life-saving surgeries for children, kids are being put on a waitlist sometimes for months, upwards of years now, and it's getting worse by the day."

Jacques said she would like to see youth fully vaccinated before the return of school in the fall so they can go back to in-person learning. She also said would like to see more virtual support programs for students, especially for Francophone children.

“A lot of them are English strictly. So there’s a ton of youth that go to this one organization that exists, and then they're not able to support everyone,” she said. “There's so many kids that need help and so little resources.”

Mitton encouraged other families to support the campaign so that politicians are aware of the impact this crisis is having on them and their children.

"I know parents are really tired, but if they want to do something for their kids, doing things like participating in #codePINK where we're asking people to draw a pink cross on your hands, take a selfie, and explain why you're declaring #codePINK like what's your story? The government needs to hear those things in order to act," she said.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, here are some resources that are available.

- Canada Suicide Prevention Helpline (1-833-456-4566)

- Kids Help Phone (1-800-668-6868)

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (1 800 463-2338)

- Crisis Services Canada (1-833-456-4566 or text 45645)

If you need immediate assistance call 911 or go to the nearest hospital.