Canadian researchers have discovered that chemotherapy can change cancerous cells in patients with acute myeloid leukemia, allowing them to camouflage themselves before causing a relapse of the disease.

The new research from McMaster University suggests that while chemotherapy can effectively send acute myeloid leukemia into remission, it also has a yet-unexplained effect on blood that allows the cancer to return in some patients.

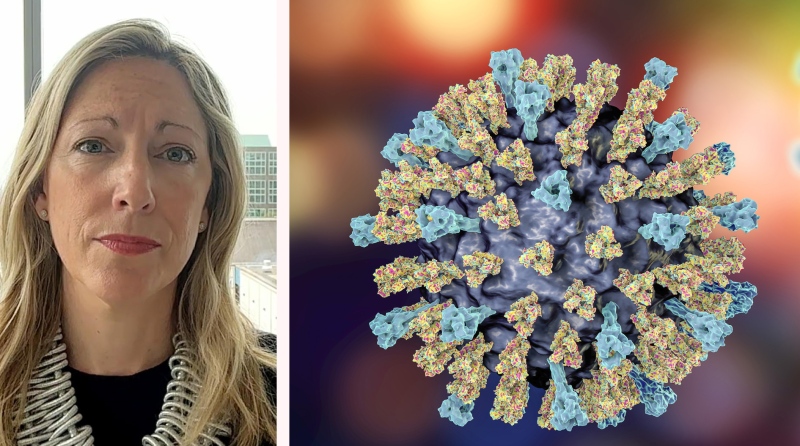

Mick Bhatia, the lead author of the study published Monday in the Cancer Cell journal, said researchers are still trying to understand exactly how the chemotherapy allows cancer cells to change and “masquerade” before setting the stage for a relapse.

“Chemotherapy works fantastically and is very good, but a year, two, sometimes five years later, (the cancer) comes back,” Bhatia, the director of the McMaster Stem Cell and Cancer Research Institute, told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview from Hamilton, Ont.

The study suggests that chemotherapy “allows something to be secreted in the blood and serum,” causing changes to the patient’s blood that induce the “masquerading” of cancer cells, Bhatia said. The chemo appears to indirectly change the cancer cells, but researchers are still trying to figure out the mechanism behind that process.

“Based on this finding, we’ve set up a whole new campaign of research projects to find out how exactly this happens,” he added.

In the study, which spanned more than five years, researchers studied 30 patients with acute myeloid leukemia and injected donated cancer cells into lab mice.

The mice developed leukemia identical to the disease in humans and essentially became “little avatars” of each patient, Bhatia said.

By studying the changes to the cancer cells after chemotherapy, researchers realized that some of those cells changed and went undetected. Bhatia likened it to a crime suspect who alters her appearance after seeing a police bulletin with her description.

“If the description is: ‘Female, 5’10,’’ with a blue hat,’ you would go into a crowd and that’s what you would look for,” he said.

“If it turns out that she puts on a beard, puts lifts in her shoes so that she’s six feet tall and a black trench coat, it’s the same person but looks quite different. That person is responding to the knowledge that they’re being looked for.”

Bhatia said many cancer researchers previously believed that cancer relapses were caused by chemo-resistant dormant cancer cells. But the discovery of the so-called “cancer regenerating” cells that can hide in the bone marrow of a leukemia patient opens the door to further research and new treatment possibilities.

Bhatia said these camouflaged cancer cells need to be targeted.

That could mean adding existing or new drugs to a patient’s treatment regimen to inhibit certain cell proteins. As part of the study, researchers tested a drug used for bipolar disorder on four samples of these cells, finding the growth of cancer delayed. Further studies are planned on other drugs to keep these cancer cells in check.

Dr. Ronan Foley, an oncologist at the Juravinski Hospital in Hamilton, Ont., said the research done by Bhatia and his colleagues is “very sophisticated.”

“It takes us to another level of being able to understand leukemia,” Foley told CTV News.

He said oncologists already suspected that chemotherapy plays a role in leukemia relapses, and the study “opens up the door for us to consider new therapies.”

Generally speaking, Foley said, leukemia comes back after treatment about 60 per cent of the time.

“And when it comes back … it is much more difficult to treat oftentimes.”

Foley said the latest research gives doctors a better understanding of why patients relapse and what can be done to improve treatments.

Although this study focused on acute myeloid leukemia cells and their response to chemotherapy, the findings are likely relevant to researchers studying different types of cancers, including brain tumours and colon cancer, Bhatia said. Researchers in the U.S. and Europe are already working on identifying and killing these “comeback” cancer cells.

With files from CTV’s medical specialist Avis Favaro and producer Elizabeth St. Philip