University of British Columbia researchers have suspended a clinical trial that gave pregnant women an erectile dysfunction drug after 11 babies born to mothers enrolled in a similar Dutch study died of a lung condition.

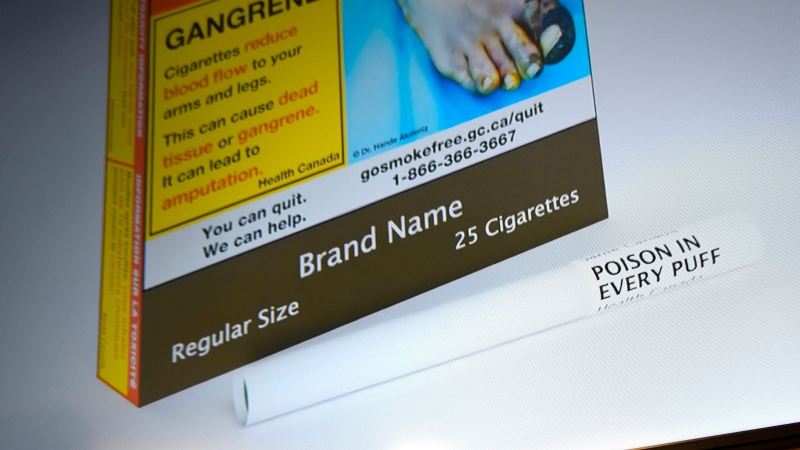

The trial, known as STRIDER, was giving sildenafil to women experiencing a condition called early intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) in which the placenta doesn’t supply enough nutrition to the fetus, increasing the risk of a stillbirth or problems after birth.

Sildenafil, which is most commonly known under the brand name Viagra, improves blood flow, so researchers had theorized that it may help increase the delivery of nutrition to placentas in cases of IUGR.

In a statement, Pfizer, the company that manufactures Viagra, says it “was not involved in any aspect of this trial, and neither funded nor provided product for the trial.”

“In addition, the Principle Investigators at the Amsterdam University Medical Centre have confirmed a non-Pfizer manufactured generic version of sildenafil was used but that no clinical trial participants were administered Viagra, Pfizer sildenafil or any other Pfizer medicine.”

Amsterdam University Medical Centre, which led the Dutch study, issued a press release on Monday saying that the trial was suspended after an interim analysis found that the drug may be detrimental to the babies after birth and had no positive effect.

Dutch newspaper de Volkskrant reports that 90 women received sildenafil and 93 received a placebo during the Dutch trial. They say that 19 babies born to mothers who got the drug died, including 11 with a lung disorder. In the control group, nine babies died but none died from the lung disorder. It’s believed the lung disorder may have been caused by the sildenafil.

The Canadian trial was being overseen by Dr. Kenneth Lim, Head of the Division of Maternal-Fetal Medicine program at UBC.

Lim told CTVNews.ca on Tuesday that he learned of the report out of the Netherlands late last week and immediately notified the study’s independent Data Safety Monitoring Board and the University of British Columbia’s research ethics board.

“The loss of a child under any circumstance is a tragedy for the parents and their loved ones, and we were very saddened and concerned upon learning of this news,” he said in an emailed statement.

“We are not aware of an increase in adverse outcomes among the 21 Canadian trial participants,” Lim added.

One woman currently enrolled in the trial was contacted and told to stop taking the pills she had received, which may have been either the drug or a placebo, according to Lim.

“We will contact the 20 other Canadian women who have already participated in the trial,” Lim said. “As long as the trial is suspended, no further recruitment will take place.”

The study had been recruiting mothers in Vancouver, Quebec City and Montreal.

“We are working cooperatively with our international research partners in the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand to better understand the cause of the results in the Netherlands, and how they relate to results being reported by U.K. and other researchers, which did not indicate any evidence of harm,” Lim said.

The UBC-led study was launched in 2017. It received funding from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research and was approved by Health Canada.

When Lim announced the trial, he said in a news release: “We’ve already done a small study that has shown promising results.”

“Growth of the babies has appeared to improve and no harms were identified, although the number of babies studied was small,” he said at the time.