Schoolchildren in Canada ate higher quality foods but still not enough dark greens in 2015 compared to those in 2004, according to a new University of British Columbia study.

The study, published in Public Health Nutrition, found that there was a 13-per-cent improvement in the quality of foods children ate during the school day.

"It's essential to look at what foods children are eating at school and how their diets have changed over time to identify challenges and opportunities to promote healthier diets among Canadian children," lead author and UBC postdoctoral research fellow Claire Tugault-Lafleur said in a press release.

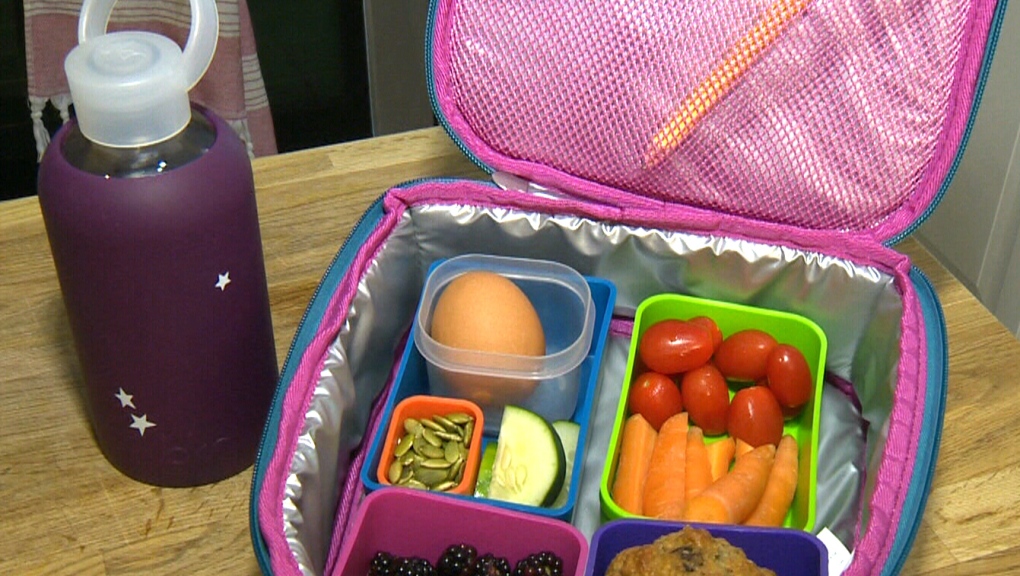

Compared to children in 2004, schoolchildren in 2015 consumed more fruits and vegetables and ate fewer calories from “minimally nutritious foods” such as salty prepackaged items and sugary drinks.

But Tugault-Lafleur’s team stressed the diets of children still need “substantial improvement for children to meet recommendations in Canada's Food Guide.”

Her findings come out on the heels of a separate global survey that found that Canada had the most sodium in packaged foods, while also containing the lowest amount of saturated fats.

CHILDREN STILL NOT EATING ENOUGH DARK GREEN VEGETABLES

Her team examined data from Canadian Community Health Surveys conducted in 2004 and 2015 which involved 7,000 children between the ages of six and 17.

“We also wanted to see whether children's diets at school changed the same way for everyone over time,” Tugault-Lafleur said, adding that her team noticed there were noticeable differences in what children ate across age groups and provinces in 2004.

They judged the nutrition of the foods that children ate using a measure called the Canadian Healthy Eating Index, which assigns a score based on 11 dietary components.Besides their main findings, Tugault-Lafleur’s team found that in both the 2004 and 2015 surveys, children didn’t eat enough dark green and orange vegetables, whole fruit, whole grains, and milk and alternatives.

Food insecurity -- defined as having inadequate or insecure access to food due to lack of money -- led to a slightly lower quality of food which children ate in 2015 compared to 2004.

But there could be a fix to this.

Tugault-Lafleur noted that Canada is the only G7 country without a national school food program and that there’s an ongoing effort to get one implemented.

"Interventions which help ensure that all Canadians can afford nutritious meals for their children have (the) potential of helping Canadian children move closer towards national dietary recommendations," Tugault-Lafleur said.

Other researchers have recently examined the need for Canadians eating fewer ultra-processed foods such as carbonated drinks, mass-produced cookies and ice cream, and sweetened yogurts.

Research from the University of Montreal in June linked diets high in ultra-processed foods to chronic disease and 31 per cent greater odds at developing obesity.