People who were physically abused as children appear to have much higher rates of heart disease, new research from the University of Toronto finds.

The researchers found that people who were physically abused as children were 45 per cent more likely to develop heart disease as an adult than their peers who had not been abused.

Study author Esme Fuller-Thomson, a professor at U of T's Faculty of Social Work and Department of Family and Community Medicine says her team's findings were based on data from a 2005 Statistics Canada survey conducted in Manitoba and Saskatchewan.

They looked at data on 13,000 respondents who answered a number of questions for the survey.

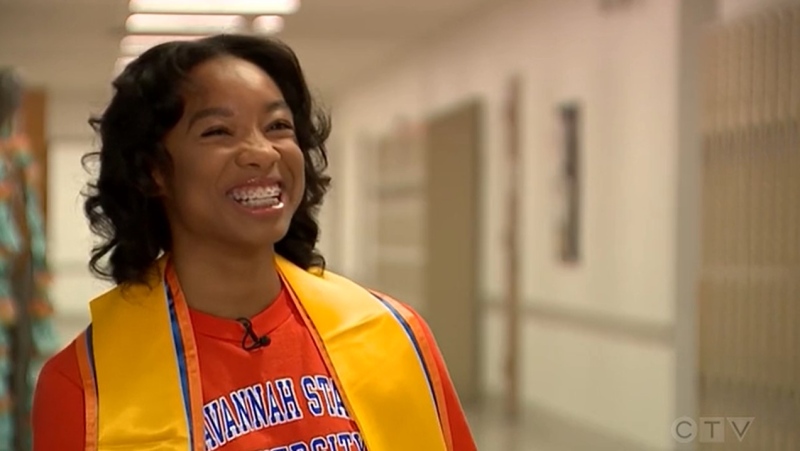

"Those questions included: while you were under 18 and still living at home, were you physically abused by somebody close to you?" Fuller-Thomson told CTV's Canada AM Friday.

Seven per cent of respondents said they had been physically abused as children. Four per cent also reported they had been diagnosed with heart disease by a health professional.

Fuller-Thomson says the childhood abuse and heart disease link persisted even after controlling for a number of factors.

"We controlled for age and sex and race and we found this big link. And our first thought was ‘Well it must be explained by health behaviours'," she said, explaining that people under stress sometimes make poor health choices, such as poor diet and fitness habits.

"Children who are abused are disproportionately likely to smoke, drink excessively, etc.," she notes. "So we adjusted for that, statistically, and the relationship still existed.

"So the next thing was, ‘Maybe it's depression.' Because if you are depressed you are more likely to develop heart disease, and there's lot of literature that says that children who are abused are more likely to develop depression in adulthood. So we put that in the equation too. But still it was there.

"So then we said. ‘Okay, we need to put in everything else that we know affects heart disease: a history of high blood pressure; poverty -- poverty is not good for your health in any outcome; education, because children are more likely to leave school early if they're abused. And so on and so on. We put 15 things in and we still found this 45 per cent higher odds."

The findings are published in this month's issue of the journal Child Abuse & Neglect.

Fuller-Thomson says the findings need to be replicated in more studies to conform the link. "But it's a provocative finding," she says.

She notes that while everyone needs to do what they can to reduce their risk for heart disease, such as eating well and exercising, "perhaps, if you have a history of childhood physical abuse, you might need to be even more vigilant about those health behaviours."

Co-author John Frank, director of Scottish Collaboration for Public Health Research and Policy, notes that future research is needed to understand what mechanisms might explain why childhood physical abuse might be linked to heart disease.

"Like many previous studies linking early life characteristics and experiences with late life serious disease, this study does not explain precisely how such links operate, biologically; further research will be required to understand that process," he said in a news release.