Larry D. Rose is the author of 10 DECISIONS: Canada’s Best, Worst, and Most Far-Reaching Decisions of the Second World War. He worked for more than 45 years in broadcasting, and his military background includes seven years in the armed forces reserves. July 10, 2018 marks the 75th anniversary of Operation Husky, the invasion of Sicily.

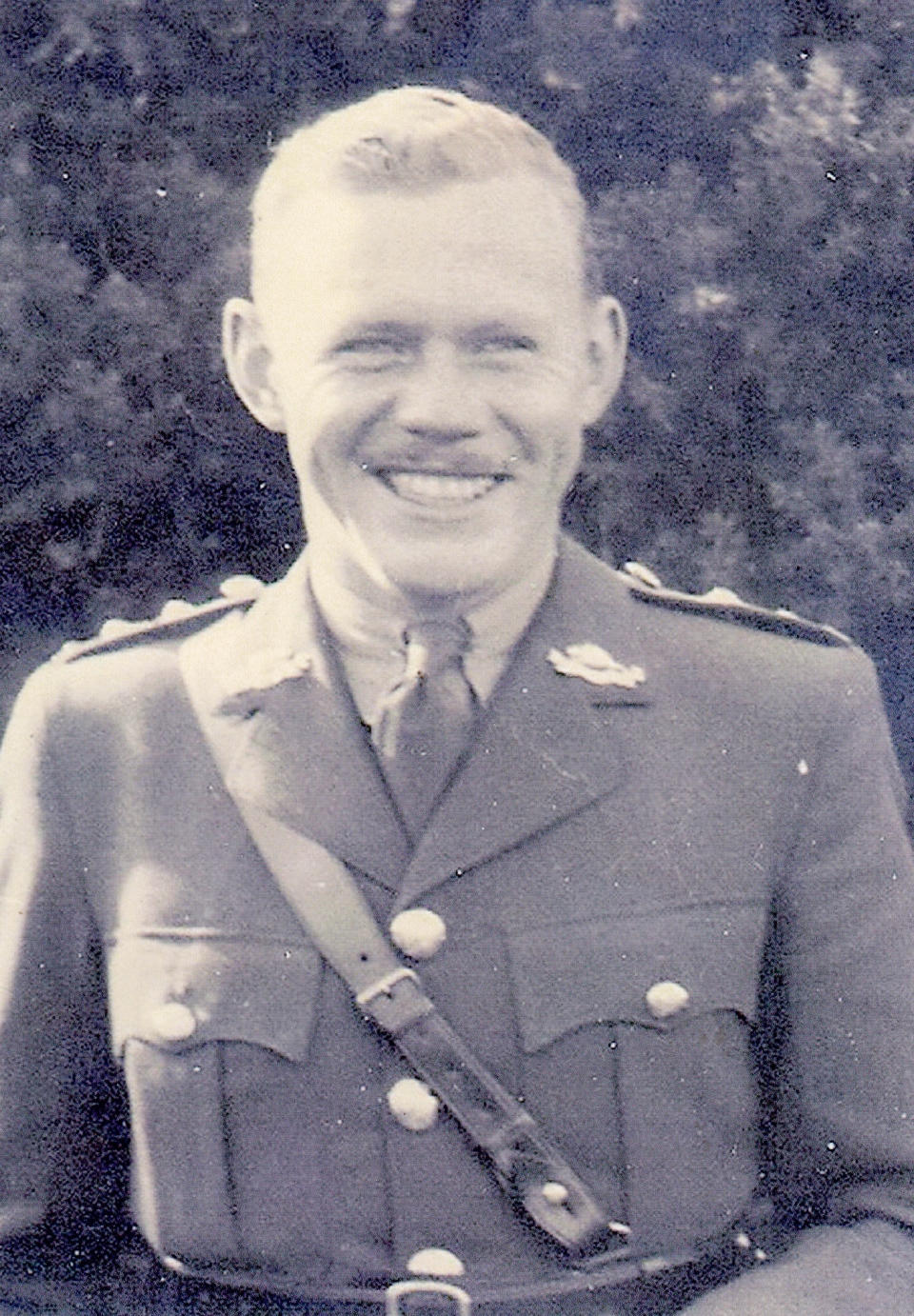

On a blistering day in 1943, Sheridan “Sherry” Atkinson, a young Canadian infantry lieutenant, stormed ashore on a beach in southeastern Sicily. The next day, Signalman Al Stapleton jumped off a landing craft, plunged into six feet of water and scrambled his way to shore on the same beach.

It was the start of Operation Husky, the Allies’ first attack on Fortress Europe in the Second World War. July 10 will mark Husky’s 75th anniversary.

Almost 3,000 ships and landing craft took part in what was the largest amphibious operation in history to that time. Twenty thousand Canadians from the 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Army Tank Brigade—including Lieut. Atkinson and Signalman Stapleton—made up part of General Bernard Montgomery’s fabled Eighth Army in the attack.

The United States’ Seventh Army, commanded by Lieutenant-General George Patton, landed to the west of the Canadians. Small numbers of Royal Canadian Air Force airmen and Royal Canadian Navy sailors also took part in the attack.

Thousands of Canadian soldiers had been waiting three long years to get into battle. Earlier in the war there had been the ghastly Canadian disasters at Hong Kong and Dieppe, but the Sicily invasion marked the first sustained campaign for the Canadian army in the war. It also signalled the start of the much larger Italian campaign.

Sherry Atkinson, a member of the Royal Canadian Regiment, said there was “organized chaos” prior to his landing. His team of 30 men worked in complete darkness and in dangerously heavying seas to help transfer their trucks and anti-tank guns from a huge transport ship onto a much smaller landing craft for the run into shore.

The young officer said that on the way in to the beach he could hear the whoosh of 15-inch shells from the bombardment ship HMS Roberts passing overhead. Some soldiers said the shock wave effect was so powerful it was as if their shirts were being ripped from their backs. On shore, opposition by defending Italian soldiers was light, but Mr. Atkinson recalls that a young officer was killed by a sniper right on the beach.

As for Al Stapleton, the day after he landed, two of his best friends were killed in a Luftwaffe strafing attack. The three had joined the army together in 1939.

By August 17, the Canadians, British and Americans had cleared the Axis forces out of Sicily. By then, Italian dictator Benito Mussolini had been toppled from power, the Mediterranean Sea lanes were opened, and the way was clear for the invasion of mainland Italy.

Today, Mr. Atkinson, who is 96, and Mr. Stapleton, 98, are among a handful of Sicily veterans and among a thinning rank of those from the Italian campaign as a whole who still survive.

On the Italian mainland, Capt. Jack Rhind, a member of the 11th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, fought in the mud and cold of Monte Cassino. He and members of his battery were in full view of the Germans on the heights above them for the entire battle. Cassino was the site of the historic monastery which was bombed during the battle, one of the most controversial acts of the entire war.

Today, Mr. Rhind still resides in his hometown, Toronto. He is 98 but looks and sounds much younger. His conversation is lively and articulate but he remains reflective about those years. He said the German soldiers he captured were “basically just like us, just ordinary guys.”

Another veteran from the Italian campaign is 98-year-old Hugh Baker who was aboard a convoy that was bombed on the way to Italy. The ship next to his was sunk. Mr. Baker was a member of the Queen’s York Rangers of Toronto but spent the entire time in Italy on detached duty at a headquarters. He and his brothers Norman (aged 101) and Gordon (92) all served in the army and, incredibly, all still survive.

Since the war, many veterans have returned to Italy to remember the campaign and honour those who died. Mr. Atkinson returned to Sicily five times. Mr. Stapleton returned in 2014, stopping at the cemetery at Agira where many of the 562 Canadians who died in Sicily are buried. Among them are Mel Quick and Teddy Kroon, Mr. Atkinson’s friends who were killed in the strafing attack on July 12, 1943.

In 1964, Mr. Rhind returned to Italy with his wife, Elizabeth (since deceased) and was able, with the help of a diary he kept, to locate some of the exact gun positions he had occupied. Among his memories is the terrible toll the fighting took on civilians. Their suffering was “indescribable,” he said. “Whatever the Germans hadn’t wrecked, we did.”

Today the number of Second World War veterans from all services and all theatres who still survive may be as low as 40,000. Their average age is about 93. When it is recalled that more than one million Canadians served in the Second World War, those numbers are disheartening.

Hugh Baker has moved to the Veterans’ Wing at Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre in Toronto. Mr. Stapleton and his wife recently moved into an assisted-living home. Mr. Atkinson had a near fatal flu setback this past spring.

With the number of survivors dwindling, sometimes it remains for their families to speak on their behalf. Rod Hoffmeister is the son of Bert Hoffmeister, who commanded the Seaforth Highlanders regiment in Husky. Major-General Hoffmeister died in 1999. Rod Hoffmeister said his father and the Canadians generally learned a lot in Sicily.

“They were perfectly suited for this kind of operation,” he said.

The Seaforths were from Vancouver and many of them were woodsmen, or, like his father, hikers who enjoyed the wilderness.

“One of the great attributes of the Canadians was their adaptability,” said the younger Hoffmeister, who is today the Honourary Colonel of the Seaforths.

What the Canadians accomplished in Italy has long been overshadowed by the Normandy invasion of 1944. Mr. Atkinson commented, “God bless those guys and I wouldn’t want to take anything away from them but the participation of Canada in the Italian campaign ended up in filing cabinets with no recognition at all, which is sad."

He said, “An important thing that hasn’t been covered off is that in Italy we held 100,000 German troops captive. If we didn’t hold them, they would have been available for D-Day.”

Even long after the war, many veterans did not talk much about their Second World War experiences. Mr. Stapleton’s son, John, said in the 1970s he was astounded to hear for the first time that his father had been instructed on the top secret German Enigma coding machine.

Breaking the Enigma machine was one of the great intelligence coups of the war. Al Stapleton had not said a word about it for 30 years after he left the army. Nor did he say anything about what happened to his two friends that day in Sicily.

Hugh Baker, when asked if Canadians today remember much about Husky or the Italian campaign, seems resigned.

“Not really,” he said, sadly. Mr. Rhind, who became a top insurance executive after the war, said he is embarrassed by what he called the “hero-izing” of men like himself.

He said he only did what so many young men and women of his generation did but he thinks it is different for those who died and for their families. “That is what people should think about.”

Sherry Atkinson, Al Stapleton, Jack Rhind, and the Baker brothers faced the perils of the Second World War and survived. They recall their contribution to Operation Husky and to the fighting on the Italian mainland with very mixed emotions.

Today, bent by time, sorrowed by the loss of many of their friends, but still valiant, they soldier on.

Larry D. Rose is the author of 10 DECISIONS: Canada’s Best, Worst, and Most Far-Reaching Decisions of the Second World War (Dundurn, 2017).