HALIFAX -- Her story has become widely known and her case linked to efforts to combat the pernicious effects of cyberbullying.

The young woman's name is a touchstone for governments and other families struggling with the sometimes tragic consequences of persistent online harassment and, in her case, an alleged sexual assault that resulted in child pornography charges that are now before the court.

But in an ironic twist, her parents say they are restricted in telling her sad narrative or advocating on her behalf because of a statutory publication ban intended to protect her by shielding her identity.

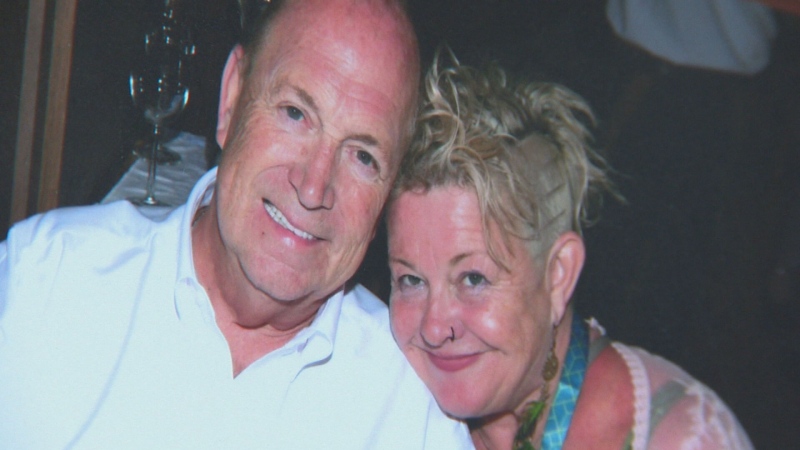

"I think it's actually ridiculous -- no one was here to protect her when she was here and now they're talking about protecting the victim's rights, so it's just kind of a mockery and a slap in the face," said the teenager's mother, who can't be identified under the ban.

"Her story has helped so many other people ... so it is really important to not silence people who are already scared to come out and tell their story."

The ban was upheld by the provincial court in Halifax after two teens were charged with distributing child pornography in connection with the case. One of them is also charged with making child pornography.

The girl at the centre of the case died last year following a suicide attempt.

A judge upheld the ban on any information that might identify her, as required by the Criminal Code, which states that a judge "shall" order such a ban in every case where child pornography is alleged.

Media outlets argued the ban should be overturned, but Judge Jamie Campbell ruled last month that he had no ability under the law to lift it.

Still, his 20-page decision outlined the awkward problem and unintended consequences of having to follow the Criminal Code section and, in his words, apply "the ban that nobody wants."

"Under section 486.4(3) the judge has to impose the ban even if no one asks for it, no one wants it, no one thinks it makes any sense at all, and it will have no real effect at all," Campbell wrote.

"Whether there are exceptional circumstances is irrelevant."

The restrictions came even after the girl's family wrote directly to the court to ask that it not be put in place and that her name be used in the proceedings and any other publications about the case.

In a one-page letter, the parents argued that their daughter's story has been used to "facilitate legislative reform and raise awareness of issues that are relevant to Canadians." Taking that away would limit their ability to continue that work, they said.

Despite that, the judge reasoned that if he stretched the law to accommodate the demands of this particular case he ran the risk of setting a precedent that could lead to the identification of victims in other child pornography cases.

Campbell said the Criminal Code provision prevails over other statutes including the Youth Criminal Justice Act, which allows parents to waive publication bans if their child dies.

It's a finding that frustrates her parents, who say they will continue publicizing her name, including on social media and on T-shirts in response to the court decision.

"I think we've done an awful lot of good things because of all the issues surrounding her case, so it's hard now to try to make these kinds of arguments if we can't give an example of what the problem is," said her father.

"After all the publicity around the case to suddenly come up and say, 'Oh by the way, no one's allowed to talk about this,' it just seemed really out of place to us."

He added that the family is considering a Charter challenge that would argue the ban infringes on their right to freedom of expression.

Legal experts say that could be a tough fight as the courts might not want to undo a law put in place to assure victims that their names would not be made public.

"It would be a difficult thing to do for anybody who's a victims' rights advocate to challenge something that is at its core designed to protect victims," said David Fraser, a Halifax lawyer who specializes in privacy issues.

Wayne MacKay, a lawyer and cyberbullying expert, said the case is very unusual and highlights a deficiency in legislation that imposes a blanket approach to unique situations.

He suggests a way around it might be to seek a constitutional exemption that would be so narrow in scope that it wouldn't be able to be applied to other cases.

"What is the possible benefit from the publication ban? There really doesn't appear to be one," he said. "The (Criminal Code) section should stay, but making an exemption in a reasonably unique and clearly defined case like this seems to me to be the right answer.

"This really puts the whole case back in the closet so people can't talk about it by name."

Campbell said in the ruling that the director of public prosecutions could issue a direction to lawyers not to prosecute certain cases that would not be in the public interest.

Chris Hansen, spokeswoman for the prosecution service, dismissed the suggestion.

"To make an announcement that we're not going to prosecute if a law is broken is inappropriate and unprecedented," she said. "If there is a charge brought to us, we would assess it the way we would assess any other charge."