WINNIPEG -- Despite more than one warning that Steve Sinclair was an alcoholic unfit to parent, social workers gave him back his young daughter, an inquiry into the girl's death was told Friday.

"To do this work, you need to believe that people can make positive change, otherwise you can't do the work," Heather Edinborough told the inquiry.

Edinborough was a supervisor at the Winnipeg Child and Family Services agency in June 2003, when Phoenix Sinclair was taken from her father and put into foster care. The child was taken because social workers found her being neglected as her father hosted drinking parties with friends and gang members.

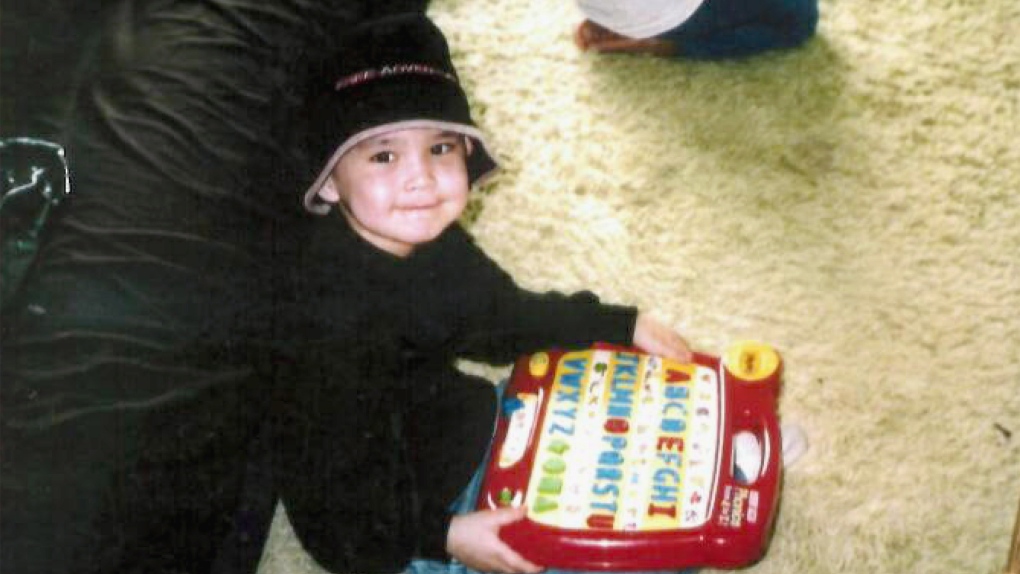

Phoenix then bounced in and out of foster care before she was handed back to her mother, Samantha Kematch, in 2004. Months later, Kematch and her boyfriend, Karl McKay, beat the five-year-old girl to death after subjecting her to horrific abuse and neglect.

The inquiry is examining how Phoenix fell through the cracks of Manitoba's child welfare system and how her death went undetected for nine months.

Soon after Phoenix was taken from her dad in 2003, an intake worker assessed Sinclair as having a "questionable parenting capacity, along with an unstable home environment, substance abuse issues."

"It would probably not be in (Phoenix's) best interests to be returned to either parent at this time," Laura Forrest wrote. Sinclair and Kematch had separated at this point.

The inquiry has already heard that Sinclair had a long history of violence and had been in foster care himself. An assessment on him, done in 1998 as he turned 18, described him as "a highly disturbed individual who should not be left in charge of dependent children".

Despite all the warning signs, social workers were aiming within weeks of the 2003 apprehension to return Phoenix to her father, and did so by October. Edinborough admitted Friday that mistakes were made, most notably that the child was returned despite Sinclair telling social workers "he was not ready."

"That's a very odd thing, for somebody to say I don't want my child back," she said. "It should have been a much bigger red flag ... as a warning about this man's capacity to parent."

Edinborough said another mistake was made at that time -- Sinclair's alcoholism was not properly considered.

"The plan ultimately became that (Sinclair's) reliance on alcohol was not so serious as to prevent him parenting his child. I know now that that was wrong," she said.

Edinborough said as a supervisor, she relied on information from the social worker who dealt directly with Sinclair -- Stan Williams. Williams, who later died in 2009, believed Sinclair was addressing his drinking problems and contradicted the earlier reports that warned the man was unfit.

The inquiry has already heard evidence that social workers failed to monitor Phoenix for months at a time.

Days after Phoenix was born in April 2000, child welfare workers took her from her parents. But she was returned to them four months later under what was supposed to be regular supervision.

A 2006 internal review of the case by Winnipeg Child and Family Services, made public only last week, found that "from October 2000 to the last contact with this family, actual service was almost non-existent."

Kematch and McKay were eventually convicted of first-degree murder. Evidence at their trial showed they had abused and neglected Phoenix, sometimes forcing her to eat her own vomit and shooting her with a BB gun. After she died, they continued to collect welfare benefits in her name and even tried to pass off another young girl as Phoenix to social workers.

The inquiry is still in its early stages. It has yet to delve into why child-welfare workers removed Phoenix from a foster home and gave her back to Kematch a final time in 2004 and what, if any, monitoring followed. Kematch and McKay's murder trial heard that a social worker who went to visit the family in 2005, was told Phoenix was sleeping and left without seeing her.