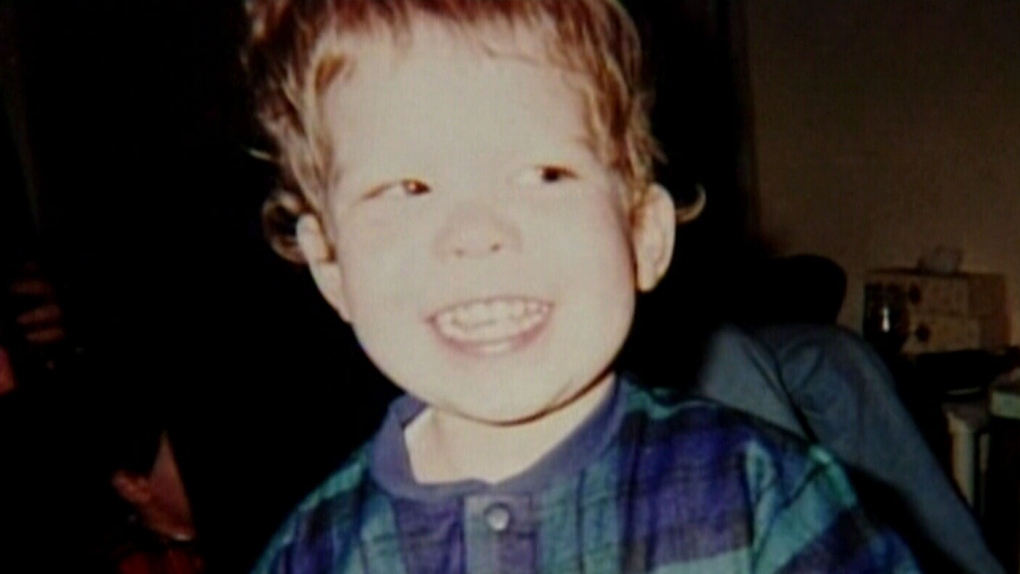

TORONTO -- Richard Baldwin knew something was terribly wrong the last time he saw his frail five-year-old son, but felt powerless to ask for help from a system that had branded the grandparents who would eventually starve the boy to death as model caregivers.

Jeffrey Baldwin was months away from death, his tiny body wasting away, when Richard Baldwin hugged his emaciated son for what would be the last time. All Jeffrey said was, "daddy," Baldwin said.

"I knew his health was failing him and I knew he wasn't doing very well," Baldwin said as he wept at the coroner's inquest into his son's death.

"I wanted to take him out of the house so bad, but I was afraid that they would charge me for kidnapping then I would never see him again. I wanted to so bad."

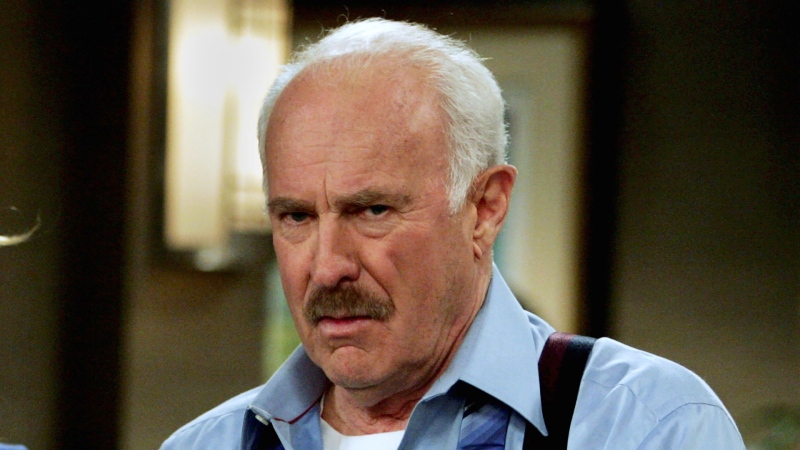

The house was that of Elva Bottineau and Norman Kidman, who were granted custody of Jeffrey and his three siblings first by children's aid societies then permanently by the courts.

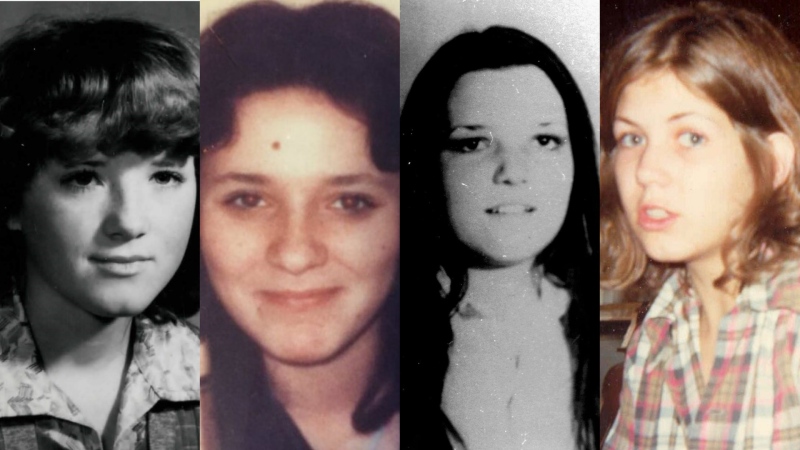

It was only after Jeffrey's death that the Catholic Children's Aid Society discovered that both Bottineau and Kidman were each convicted years before of abusing her children from a previous relationship.

Jeffrey felt so small the last time he hugged him, his father said. At the time of his death in November 2002 the boy, almost six years old, weighed 21 pounds -- about what he weighed on his first birthday.

Even at that time, Richard Baldwin was aware of some of the abuse and neglect his son was enduring at the hands of his grandparents. But Bottineau and Kidman had legal custody of the children. And Baldwin said it didn't even occur to him to ask for help from the authorities that had taken his children away -- one just hours after his birth.

"I wanted nothing to do with her," Baldwin said of his case worker. "She had ripped my heart from my chest and stomped on it on the ground. You think I'm going to call Catholic Children's Aid? I don't think so."

Besides, he said, who would believe him? The children were taken away because the authorities had told him he and common-law wife Yvonne Kidman -- Bottineau and Kidman's daughter -- were bad parents and Bottineau was in charge of the kids now, he said.

"He didn't look very good," Baldwin told the inquest. "I never thought to get anybody involved because as far as I was concerned I didn't have any right to do that. She kept reassuring me over and over again, 'Don't worry, I'm on top of it...He's a little underweight, but he'll gain it back."'

Baldwin told Bottineau he didn't think it was right that Jeffrey and one of his sisters were locked in their room at night, he said. She told him they would drink out of the toilet or fall down the stairs otherwise, he said.

"What could I do?" Baldwin said. "She was the boss."

The two children urinated and defecated in their bedroom when they couldn't get out at night, and Baldwin told Bottineau that he didn't think it was right that she made the kids sop up their own waste, he said.

"She said, 'They made the mess, they need to clean it so they learn not to do it again,"' Baldwin said.

Baldwin told Bottineau he was concerned about the frigid temperature of the children's bedroom in winter, he said. She told him they had extra blankets and flannel pyjamas, he said. The inquest has heard they had minimal blankets and slept in their underwear.

Bottineau got her "claws" into everyone around her and "manipulated" them into doing what she wanted, Baldwin said. That included getting the rest of the family to make accusations of Baldwin and Kidman, suggesting they were unfit parents.

They were young -- he was 19 and Kidman was 17 -- and in high school when they had their first child, he testified. A neighbour called children's aid after the couple fought outside, leaving the baby girl unattended in the home.

When a case worker showed up the next day, Richard Baldwin was surprised to see her accompanied by Bottineau and armed with various other accusations, he said.

Bottineau had told the Catholic Children's Aid Society about Baldwin and her daughter's fights, information gleaned -- and twisted -- from Baldwin's frequent telephone conversations with his mother-in-law, he said.

"She told me I could trust her," Baldwin said. "We could talk about sex, drugs, life...She was like, 'Any time you have issues and you want to speak or talk I'll listen...not knowing that everything I told her she would use against me."

Bottineau and Kidman got custody of the baby, though Baldwin thought it was temporary. He didn't fully understand the court process, he said.

"All I remember them saying was this was best for her," Baldwin said. "Later down the road when we got our stuff together we would get her back. I didn't realize at the time that we weren't getting her back."

As with their other children who were taken away, Baldwin and Kidman wanted to get help to learn better parenting skills and get their children back, but the supports weren't there, he said.

Jeffrey and his other sister were apprehended after staff at a welfare office reported seeing Kidman shake the children. Baldwin said it never happened. A previous children's aid report on Baldwin and Kidman's care of Jeffrey and his sister said the kids were healthy, but exposed to violence.

At that time Yvonne Kidman was already pregnant with Jeffrey's younger brother, and he was taken away at the hospital, hours after he was born. He too was delivered to the care of Bottineau and Norman Kidman, this time by the York Children's Aid Society, because of where the young family lived at the time.

A children's aid home study recommended it because "his maternal grandmother is an experienced caregiver who remains at home full time," the inquest heard.

Each time Bottineau and Kidman got custody of one of the children, the file with the children's aid society was closed.

Their treatment of Jeffrey -- and one of his sisters, who suffered much of the same abuse as Jeffrey -- worsened once the younger brother was in the grandparents' home, Baldwin said.

By court order he and Kidman were only allowed a few hours of supervised visits with their children each month, but toward the end of Jeffrey's life, Bottineau would sometimes cancel them, telling them Jeffrey was sick and they couldn't see him, Baldwin said.

A month or two before Jeffrey died, the parents were supposed to pick him and his sister up for a weekend visit. Jeffrey was too sick, they were told. So only his sister went home with their parents, Baldwin said. He bathed her three times when she got there, she smelled so badly of urine, he said.

The six-year-old girl didn't reveal details of what life was like for her and Jeffrey in their grandparents' house, Baldwin said. She just cried when they were leaving their house to bring her back.

"She was just saying she didn't want to go back, she didn't want to go back," he said.

"I just promised her that in the new year, 'You're going to live with mommy and daddy again...You and Jeffrey can come live with us."

Bottineau and Kidman are serving life sentences for second-degree murder.