OTTAWA -- The leader of the country's national Inuit organization says his people are also dealing with devastating rates of suicide.

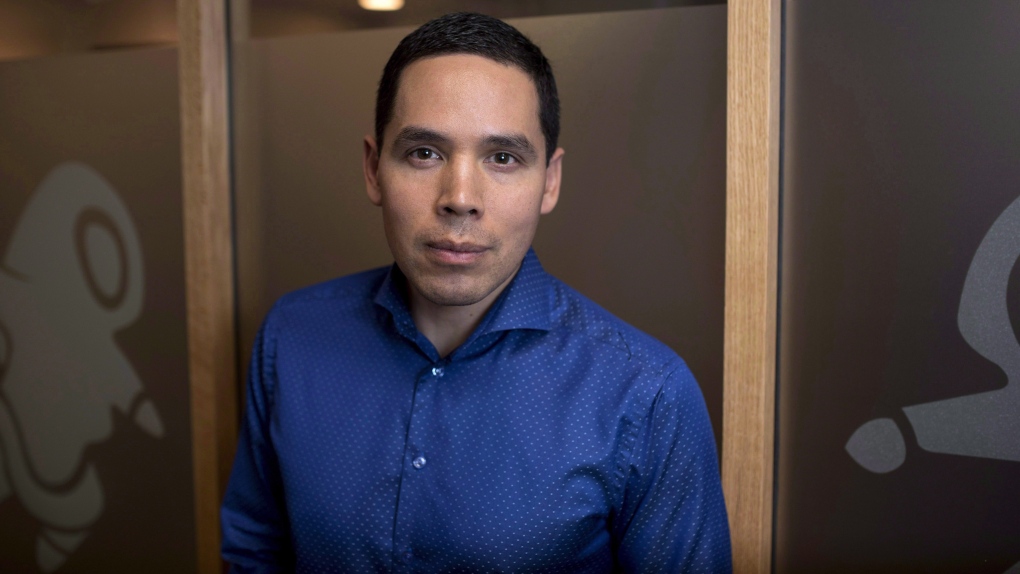

The "heartbreaking" suicide crisis in the First Nation community of Attawapiskat has become a touchstone moment for how mental health issues affect Aboriginal Peoples, Natan Obed, president of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, said Monday.

Obed watched the House of Commons emergency debate on the issue last week -- a discussion he was pleased to see.

"I am thankful for the leadership of (NDP indigenous affairs critic) Charlie Angus in bringing the issue forward," Obed said in an interview with The Canadian Press.

"I was sympathetic to a lot of members of Parliament who shared stories and it was obvious that a number of parliamentarians are passionate about this issue and really want to see positive change, for not only Attawapiskat, but all indigenous communities in Canada, including Inuit."

Obed fears, however, that Canada is still stuck treating indigenous suicide in a very different way than other public health crises.

"We could have a much more informed debate and a much more sophisticated debate and not leave it up to communities to come up with answers to the entire problem," he said.

Obed noted there are more than 1,000 attempted suicide calls each year in Nunavut, a territory of just over 30,000 people.

The suicide rate for Inuit is 11 times higher than the national average and the majority of deaths by suicide are people under 30, according to Statistics Canada.

ITK is also working on identifying more specific suicide figures by working with coroners in the four main jurisdictions where Inuit live -- Nunavut, Nunavik (northern Quebec), Nunatsiavut (northern Labrador) and the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories.

Obed said he hopes the government will move forward on a plan designed specifically to help Inuit people.

"It is going to take a lot of money and a very fundamentally different way in which we treat this particular issue," Obed said.

"When I talk to anyone who has power, anyone who has influence in the area of suicide, it is as if we are taking all the things that actually matter, the societal change issues, off the table and to say 'OK, what can we do to reduce Inuit suicide?'

"I'm supposed to answer that question and our communities are supposed to come up with a solid answer to the question without (government) doing the things everyone in the world knows that you would do to transform a high-suicide rate society into a low-suicide rate one with the infrastructure ... the environment in which our children are raised. So then we get into the question of 'What are people willing to do instead of what needs to be done'?"

Obed also said he is worried about some of the things the Liberal government has said in the federal budget about the funding it is providing to Aboriginal Peoples.

"There's a lot of statements that this government has made that, I think, are quite frankly irresponsible," he said.

"They keep talking as if the clean water funds and the education funds are indigenous funding when really they are First Nations, on-reserve funding."

Obed said the government has acted to address some long-standing issues, which he applauds as a Canadian, but he does not see the investments as "transformative" from his perspective as an Inuit leader.

"Inuit get caught up in this all the time where something can be announced and it has nothing to do with our reality because we are not on reserves and our funding relationships are so different," Obed said.

"I am disappointed that everything seems to be politicized to the point where it is preying upon peoples' ignorance of the complex realities of funding between the federal government and indigenous peoples."