TORONTO -- Throughout her career, registered psychotherapist Elda Almario has spent a great deal putting the mental health of children she works with ahead of her own. But during the pandemic, she says, it’s become even less likely for her to “take a break and reflect.”

Over the past few months, Filipina front-line workers like Almario have found an outlet to relieve bottled-up anxiety, loneliness and fear: Writing their stories down and sharing them.

“Allowing space for my experience to come to the surface became a form of self-care for me,” Almario told CTVNews.ca in an email. “It was great to have a voice and be heard especially during a time when I have been so focused on my work due to increased demands and complex needs.”

The “Stories of Care” writing initiative, run through North York Community House in Toronto, virtually brings together front-line workers such as nurses, retail workers, at-home caretakers, dental hygienists, and cleaners, to share burdens they’ve mostly carried alone.

“It gives me strength, I feel encouraged because I know that no matter what we are facing, we face it with courage, resilience, and positivity and we continue to love what we do,” Olivia Dela Cruz, a paid caretaker of a household of six children, told CTVNews.ca in an email. “My respect [is for] all frontline workers because they all put others before themselves.”

Jennifer Chan, the lead organizer of the initiative, told CTVNews.ca in a video interview that the writers “feel seen and heard in a completely different way.” She said one participant told her, “it was so meaningful to get to write my story and just spend time thinking about me.”

Filipinx people play a crucial role on Canada’s front lines, making up one in 20 health-care workers, according to one study. A third of internationally trained nurses in the country are from the Philippines, according to the Canadian Institute for Health Information; with Filipinos making up 90 per cent of migrant caregivers providing in-home care under Canada’s Caregiver Program.

EXPERIENCES CAPTURED IN ART

Chan was inspired to start the program through her work with North York Community House, where she regularly consults with caregivers from the Philippines, who need help filling out government documents.

She and her colleagues were noticing “a lot of stuff coming to the surface” and they wanted to give them an outlet.

“Stories of Care” began last summer as a six-week writing course for a few Filipina front-line workers, and has since grown in attendance and centred on less-time-intensive sessions.

As of last Friday, some of the stories are now featured in a digital exhibition in the DesignTO Festival, based on three Filipinx artists who “read the stories [and] took inspiration from them,” Chan said.

One video called “Balikbayan” – a term for Filipinx people living outside of the Philippines -- shows a fruit falling to the ground, turning into a box, crossing the sea, hitting the shore and growing into a tree. This signifies people starting a new life in Canada. The title also refers to the care packages or “Balikbayan boxes” that are sent back to the Philippines.

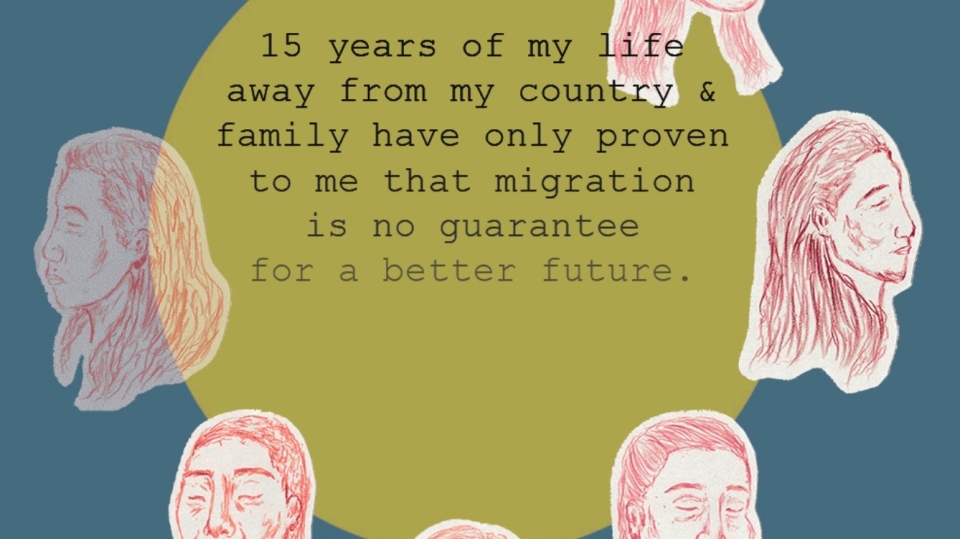

Another video features an animated circle of faces encircling alternating excerpts about workers’ fears, including getting COVID-19 on the job.

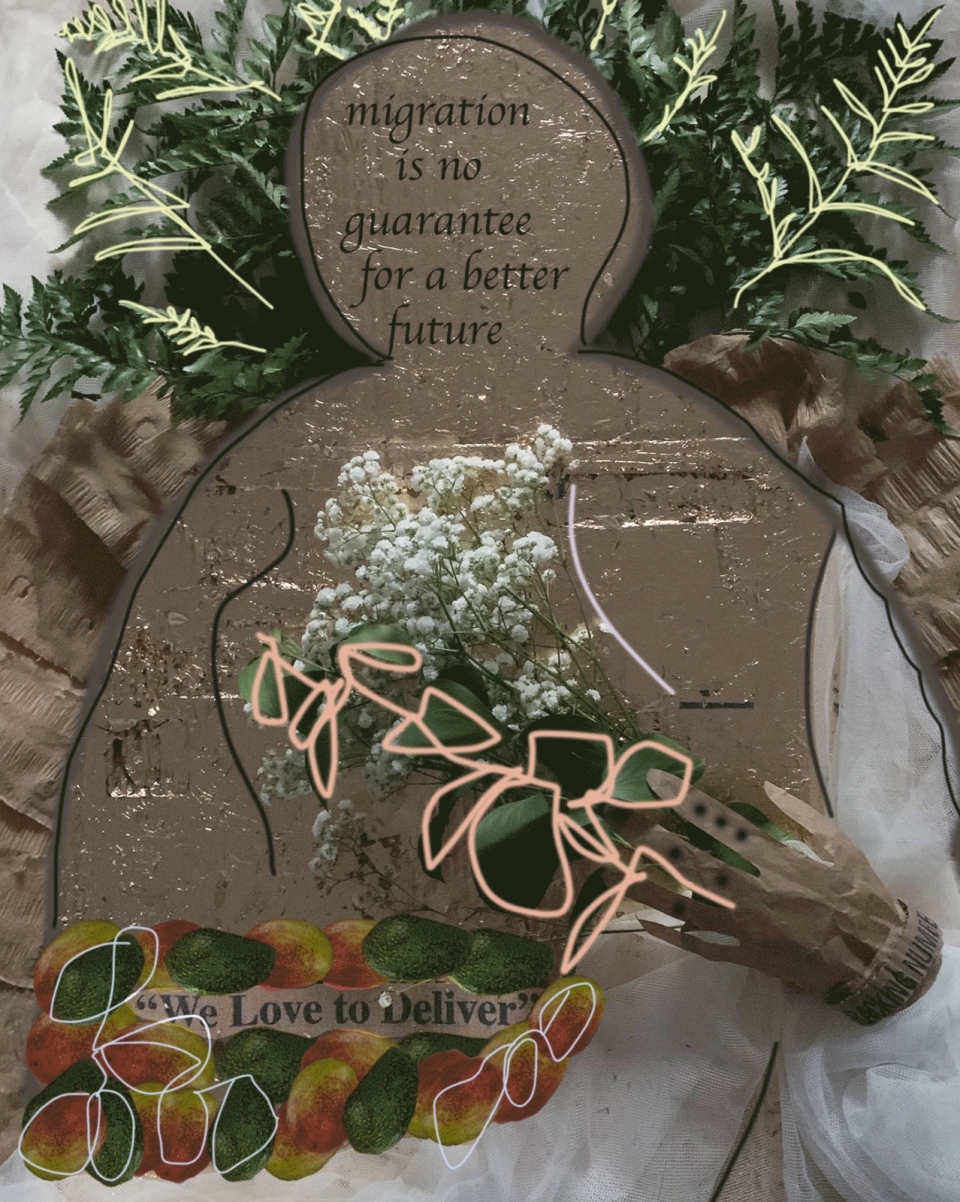

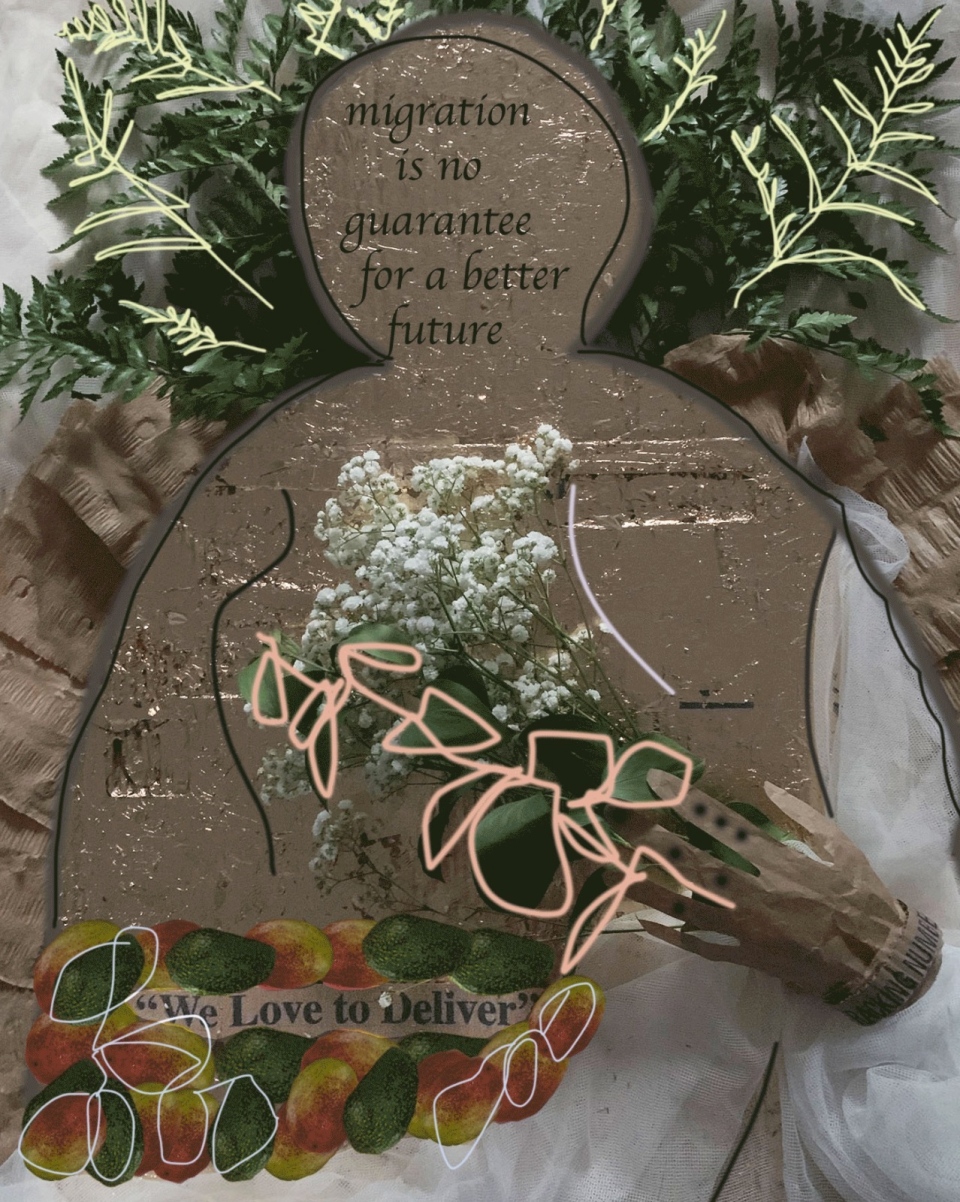

Another piece features a silhouette of a person holding a sign reading, “we love to deliver,” contrasted with alternating English and Tagalog phrases such as: “I need to sacrifice my comfort for my family,” “I didn’t want to move to Canada” and “Migration is no guarantee for a better future.”

“Having artists make renditions of our stories gives us the validation that our stories are valuable,” Gretchen Mangahas, a communications specialist and newcomer to Canada, told CTVNews.ca in an email.

“I felt the power of stories in the shared lived experiences of my Filipina sisters,” she said. “I knew that I was not alone, and that the connection opens opportunities to learn how to navigate in a new country I would call home. It has also created friendships and new avenues for sharing with others.”

FILIPINX FRONT-LINE WORKERS FEEL 'OVERSIZED TOLL'

Last fall, the Migrant Workers Alliance For Change released a damning report alleging that throughout the pandemic, migrant care workers were subjected to entrapment, long hours, and thousands of dollars in stolen wages by exploitative employers.

Chan said some writers “were feeling stuck in their employer situation” and thought about quitting, but knew it would mean they couldn’t provide for family back home and might potentially lose permanent residency status.

Medical news publication Stat News also reported that COVID-19 has taken an “outsized toll” on mental and physical well-being for Filipino front-line workers in the U.S. Chan said the same could be seen in Canada.

“They need an outlet to reflect through their own stories… we’re not hearing enough from them,” she said. Chan said attendees had a lot of cultural habits to overcome initially, including so-called “toxic positivity” and the “ongoing feeling that these women feel that they have to feel grateful to be here.”

Many worried about their families back home in the Philippines, which was hit by multiple typhoons last year. Chan said others wrote about the strict lockdown measures in the country and about “not being able to go home. Not feeling safe here or there.”

Although most people today are only being able to connect with family over video or the phone, that’s what immigrants have done for decades, said magazine editor Justine Abigail Yu, who facilitates the writing workshop in both English and Tagalog.

“Loving from afar” was a big theme in their writing, she told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview. “Obviously the conditions are quite different on an extreme level, but we’ve always had to show our family who are living in entirely different countries how we care for them and how we love them.”

The organizers said front-line workers’ feelings of isolation and homesickness while living in Canada have only been amplified by the pandemic.

Yu, the founder of magazine Living Hyphen, created an environment where Filipina workers could open up to themselves and to others.

“So many of these caregivers and our immigrant families, we just want to survive. We move to Canada, work our asses off to get by and to make sure that we’re providing for our children and there’s no room to tell stories,” she said. Yu's role involved “breaking down that barrier first and foremost.”

And the investment appears to have paid off.

“In more ways than one, we deeply resonated with each other’s experience,” Almario said. “I gained a sense of belongingness and community, the feeling of not being alone.”

Caregiver and single mother Dela Cruz agreed, saying being a part of this project “brings back so many memories that I thought completely forgotten. Stories about me that I never thought I will have the courage to share.”