Rising levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are doing more than just contributing to climate change, new research suggests; it’s also taking a toll on our food, turning once-nutritious plants into something more like junk food.

Several studies in recent years have found that, as carbon dioxide (CO2) levels rise, plants are drinking up the gas and growing so quickly, they are creating crops that have more sugar and less protein and minerals than slower-growing plants.

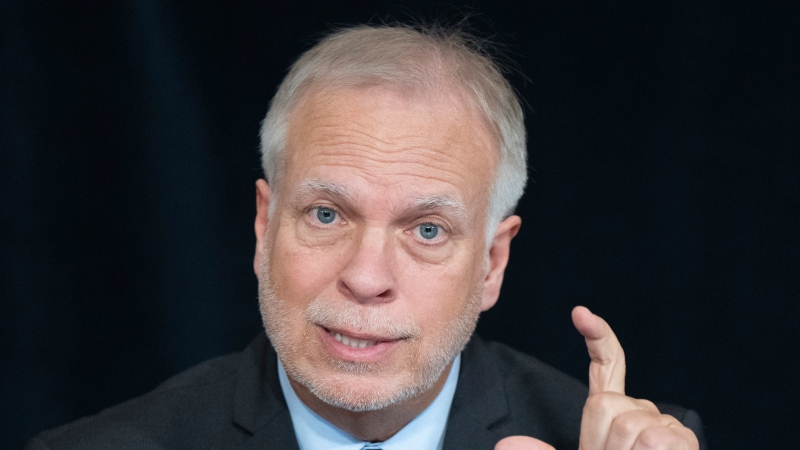

Irakli Loladze, an associate professor in biomedical sciences at Bryan College of Health Sciences in Lincoln, Neb., has noticed this change too. He has been using mathematical models to show how the nutrients of plants will continue to drop as CO2 levels rise.

“The more CO2 there is in the air, the more sugar and starch (plants) make, and that dilutes the rest of the nutrients in the plant,” he explained on CTV’s Your Morning Tuesday.

“…We know that protein levels and essential minerals like calcium, magnesium, iron, zinc, potassium, phosphorus – they all decline,” he said.

Researchers have long noted that the nutritional content of many foods has been falling over the past century. Much of that decline has been blamed on large farms choosing crop cultivars that grow the fastest and produce the highest yields, with little concern for the taste and nutrition of the plants.

But Loladze says CO2 is also playing a role in the drop of plant nutrition – and new research is adding to that theory.

One study, released this past week by Harvard researchers, looked at what will happen as rice, wheat, and potatoes are grown under elevated CO2 concentrations.

They found that the plants’ protein levels will drop by approximately 6.5 to 7.5 per cent when they are grown amid high CO2. They also project that barley protein will drop by 14 per cent when plants are grown with high CO2.

The authors of the Harvard study project that if CO2 levels continue to rise, the populations of 18 countries may lose more than five per cent of their dietary protein by 2050.

They say their results suggest that millions in sub-Saharan Africa and several south Asian countries will face protein deficiency challenges, especially in areas where rice and wheat supply a large portion of daily protein.

“So we definitely know it’s the CO2,” says loladze, who was not involved in that study. “But other factors are contributing to it, for example, depletion of soils, our chase for higher and higher yields where we essentially sacrifice quality for quantity – they all contribute.”

Loladze says it’s still unclear what cumulative health problems will be caused by plants that begin to have more starch and sugar and less protein and minerals. But he says every part of the globe will be affected.

“As CO2 concentrations keep rising, you’ll be adding more and more of that. And that will happen in every corner of the world because CO2 concentrations affect every plant and every field,” Loladze said.