If the first-ever human head transplant goes off without a hitch, a Canadian grad student will have earned a special nod of recognition.

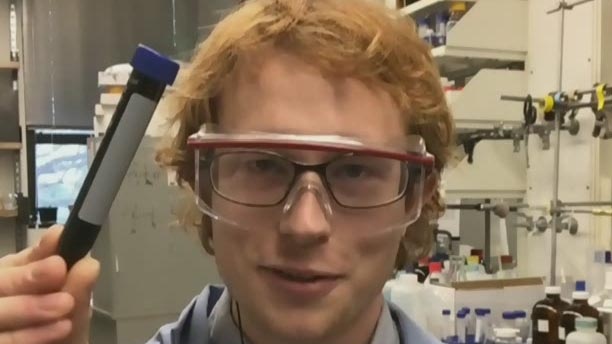

William Sikkema, a Rice University chemistry student from B.C., is preparing to lend his expertise to the landmark (and radical) procedure in the near future, with a tool designed to reconnect a severed spinal cord.

Sikkema will work with lead surgeon Sergio Canavero to transplant a terminally ill man's head onto a healthy body. The patient, a Russian named Valery Spiridonov, is currently wasting away from spinal muscular dystrophy.

If successful, Sikkema says the procedure could bring hope to many who suffer from similar diseases, as well as those whose bodies have been "ripped to shreds" in car accidents.

"The idea is you very carefully take the head off, we cool it down, and then you reconnect it," Sikkema told CTV News Channel on Thursday. "The plumbing is pretty easy," he added, explaining that all the circulatory system connections will draw on existing heart transplant techniques.

"The hardest thing is reconnecting the spinal cord, and that's where my involvement is," he said.

The Frankenstein-like procedure would be a major breakthrough in transplant surgery, but it likely wouldn't be possible without Sikkema's chemistry expertise. Sikkema plans to use a substance called a graphene ribbon to guide the cells on the patient's spinal cord, so the head can successfully link up with its new body. The material is made of a single layer of conductive carbon atoms, stretched and lined up in a long, thin ribbon.

"It's a sort of a pathway for the neurons to grow along, so it guides the neuron growth," he said. "Normally in a spinal cord after you get it cut, those neurons don't know where to grow. But this sort of directs their path."

Sikkema became involved in the radical procedure after contacting Dr. Canavero for a tete-a-tete about the doctor's plan, which was published in January. Sikkema saw a use for his skills in the procedure, and Canavero was happy to have him on board. "He was actually looking for someone like this and I just happened to reach out to him," Sikkema said.

The procedure has been performed on mice, but Sikkema says the team wants to try it on larger animals before moving ahead with a human.

He said even if the transplant works, the patient will likely need to be on medication for the rest of his life, so his body doesn't reject the transplant.

Canavero originally planned to conduct the procedure in December, but no hard date has been set.