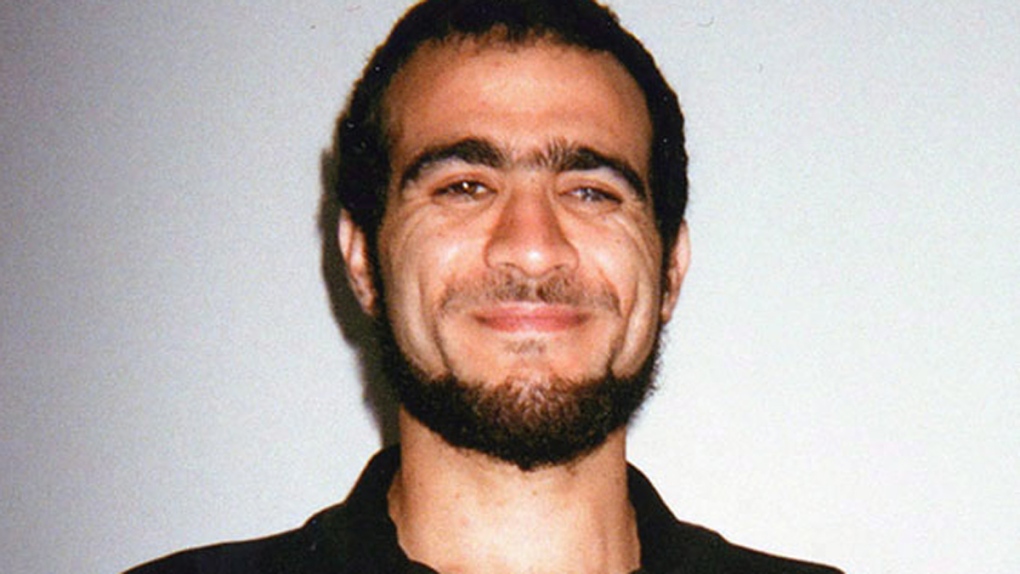

EDMONTON -- Former Guantanamo Bay inmate Omar Khadr still suffers nightmares of the firefight in which he was grievously wounded, still isn't entirely sure what happened that fateful day, but says he wants no part of violent extremism.

The information -- a rare insight into Khadr's views in his own words -- is contained in an extensive interview he did recently with a prison psychologist in support of his successful bid to be reclassified as a minimum security inmate.

"You shouldn't distort things to appease others or to suit your own agenda. I don't believe in al Qaeda killing innocents to further their belief," Khadr says.

"I hope there won't be this terrorism nonsense -- I'm not going to get involved."

Khadr's critics, including the federal government, have long branded him as an unrepentant terrorist, arguing he has failed to categorically distance himself from violent jihad.

His ideology hasn't changed, he says. Rather it has developed.

American soldiers captured Khadr, then 15, in the bombed-out ruins of a compound in Afghanistan following a brutal four-hour battle in July 2002. He had gaping wounds in his back, shrapnel in his eyes.

Khadr says he's still not sure exactly what went down in the firefight that left U.S. special forces soldier Sgt. Chris Speer dead and Sgt. Layne Morris blinded in one eye.

"I heard Americans. I heard shooting. I was scared. I had a hand grenade. I threw it over my back and it exploded. I wanted to scare them away. I wasn't thinking about the consequences. After that, I was shot," he says.

"I have nightmares of the firefight. Sometimes I can't run away in the dreams."

Following his capture, the Toronto-born Khadr was taken to Bagram and then shipped to Guantanamo Bay, where he remained for a decade.

In 2010, he pleaded guilty to five war crimes before a discredited U.S. military commission, including murder for Speer's death and spying. Even so, he says, he clings to the hope it wasn't him that killed Speer.

"I still take responsibility," he says. "If I did kill (Speer), that would be a very sad thing."

The documents, filed in the Alberta Court of Appeal, are part of Khadr's bid for bail while he appeals his war crimes conviction in the United States.

The court will rule Thursday whether to grant the federal government's request to stay an earlier ruling that he should be allowed out. A ruling in his favour could see him leave prison for the first time in almost 13 years under several restrictions that include wearing a tracking device.

If he could do things over, Khadr says, he would have tried to challenge his father -- an associate of the late terrorist mastermind Osama bin Laden -- who sent him as a 15-year-old to stay with the al Qaeda fighters in Afghanistan, initially to act as a translator for them.

They taught him to assemble improvised explosive devices, he says, and were bent on fighting the Americans if they invaded Afghanistan.

"I didn't really have an opinion but kind of agreed with them -- not because I believed it but because it was always talked about," he says.

"The thoughts were impressed upon me. In retrospect, I went along with it. My ideas were all over the place. The morality of it didn't register."

Khadr, now 28, says he just wants to learn how to live in a world he barely knows.

While dealing with women is awkward, he says he wants an intimate relationship but is prepared to wait until he sorts his life out.

What he doesn't want to do is dwell on his treatment at the hands of his American captors -- harsh interrogations, threats of rape, sleep deprivation, and being shackled in stress positions -- which his advocates have said amounted to torture.

"I cant afford to be bitter," he says.