There may be no fact of life more confounding to ordinary Canadians than gas prices.

They seem to go up at the first whisper of climbing oil prices, but don’t fall nearly as fast when barrels of oil sell for less. That’s certainly true right now.

Oil is selling for about US$55 a barrel, about half of an eight-year peak of $108 in 2014. The average barrel price that year was $88. Gas prices hit a high of $1.41 a litre in Canada in 2014 and averaged $1.28 for the year.

Prices are hovering around that level now, despite the drop in oil prices and the fact that Canada has the world’s third-largest reserve of oil. Pump prices Thursday were, according to GasBuddy.com: $1.39 a litre in Vancouver, $1.10 in Calgary, $1.15 in Toronto, $1.18 in Ottawa, $1.32 in Montreal, $1.20 in Halifax, $1.25 in St. John’s and $1.22 in Yellowknife.

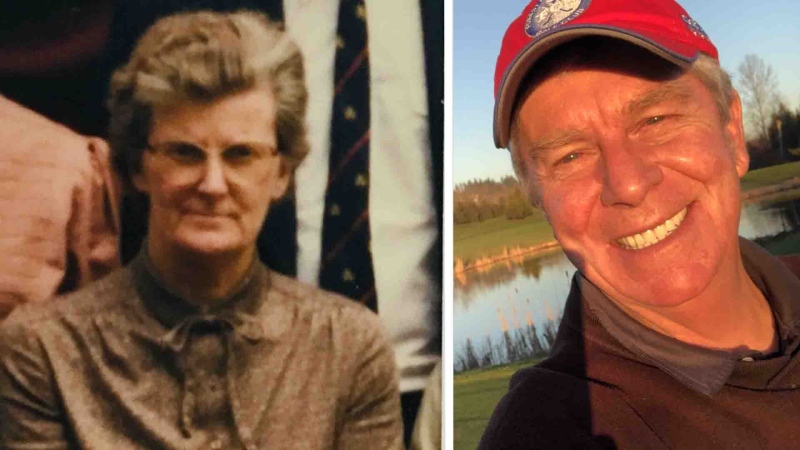

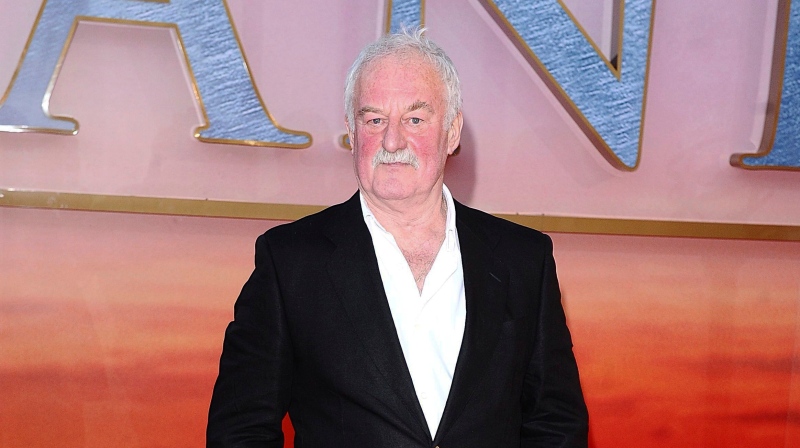

“The decline in oil prices has not been passed on to the consumer,” Jeff Rubin, a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, told CTV’s Your Morning on Friday. “It has instead been kept by the refiner who’s now getting a larger margin on their product.”

Canada is the world’s sixth-largest producer of oil, producing close to 4 million barrels a day, and only Saudi Arabia and Venezuela have more in reserve. But Rubin says much of Canada’s oilsand reserve is “unburnable” and it would cost twice as much to get it out of the ground as what it could be sold for.

It will come as no surprise to Canadians that much of what they pay at the pump is tax.

Taxes represented about 35 per cent of the price per litre in 2015. For example, in Ontario, drivers pay the base price for a litre of gasoline, plus 10 cents a litre in federal excise tax, another 14.7 cents a litre in provincial fuel tax, then 13 per cent HST on top of all that. Drivers in B.C. get to add another 6.67 cents per litre for a provincial carbon tax.

Some cities also collect a transit tax, ranging from 3 cents a litre in Montreal to 17 cents in Vancouver.

But Rubin, a former chief economist at CIBC World Markets, says taxes are not the key factor driving prices. They have been around for a long time. Instead, the biggest factor is refinery margins.

Canada exports much of its bitumen – the raw substance pulled from the oilsands – and then buys back the refined gasoline and diesel at a higher price, mostly from the United States. Canada used to do much more refining but has only 15 refineries remaining from 40 in 1970s.

“We haven’t built a refinery since 1984,” Rubin told CTV’s Your Morning Friday.

“There is one being built, the Sturgeon refinery in Alberta, that will convert 50,000 barrels a day of bitumen into diesel but, you know, you’ve got to realize that 90 per cent of all the oilsand product isn’t even upgraded into oil, let alone refined into motor fuel.”

Rubin says building more pipelines is not going to help Canada’s pump prices because they would send oil to foreign markets that pay even less than the “money-losing prices they get in North America.”

On the other hand, building more refineries would increase competition, put pressure on refinery margins and lower transportation costs, says Rubin. That would result in a closer relationship between oil prices and pump prices.