WELLINGTON, NEW ZEALAND -- Two years after a white supremacist in New Zealand livestreamed the slaughter of 51 Muslim worshippers on Facebook, French President Emmanuel Macron says the internet continues to be be used by terrorists as a weapon to propagate hate.

Macron and other leaders from tech giants and governments around the world -- including the U.S. for the first time -- gathered virtually on Saturday to find better ways to stop extremist violence from spreading online, while also respecting freedom of expression.

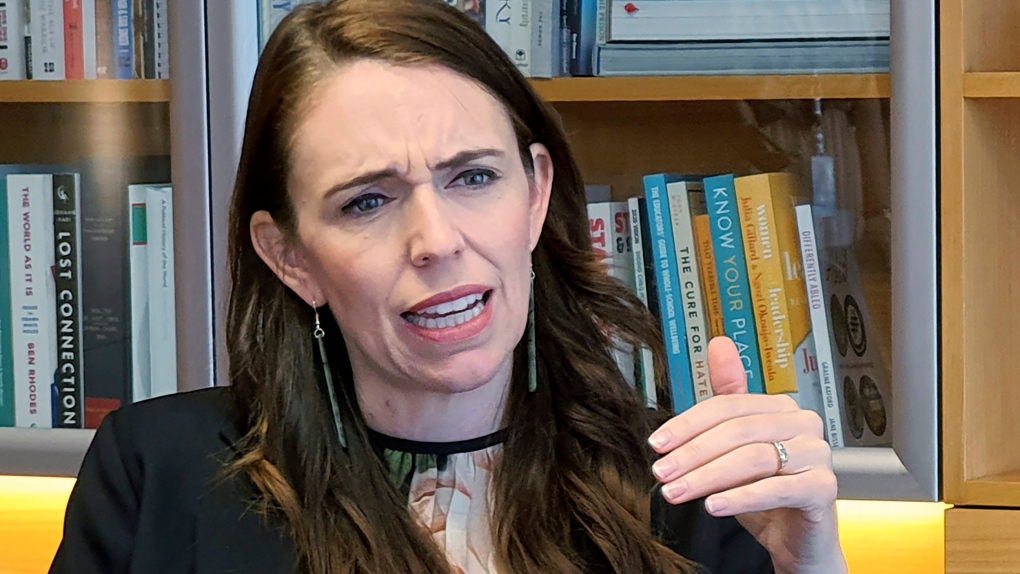

It was part of a global effort started by Macron and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern after deadly attacks in their countries were streamed or shared on social networks.

The U.S. government and four other countries joined the effort, known as the Christchurch Call, for the first time this year. It involves some 50 nations plus tech companies including Google, Facebook, Twitter and Amazon, and is named for the New Zealand city where the slaughter at the two mosques took place.

British Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in a prerecorded video that authorities in his country alone had taken down more than 300,000 pieces of terrorist material from the internet over the past decade, which he described as a tsunami of hate.

“Terrorist content is like a metastasizing tumor within the internet, or series of tumors,” Johnson said. “If we fail to excise it, it will inevitably spread into homes and high streets the world over.”

Since its launch, governments and tech companies have cooperated in some cases in identifying violent extremist content online. Ardern, however, said more tangible progress is needed to stop it from proliferating.

The meeting was aimed at revitalizing coordination efforts, notably since President Joe Biden entered office, and getting more tech companies involved. Macron and Ardern welcomed the U.S. decision as a potential catalyst for stronger action.

Macron said the internet had continued to be used as a tool in recent attacks in the U.S., Vienna, Germany and elsewhere. He said it cannot happen again, and that new European regulations against extremist content would help.

Ardern said that two years after the Christchurch Call was launched, momentum was strong. But she acknowledged the challenge in essentially playing whac-a-mole with different countries, internet platforms and algorithms that can foster extremist content.

“The existence of algorithms themselves is not necessarily the problem, it’s whether or not they are being ethically used,” Ardern said. “And so that is probably the biggest focus for the Call community over the next year.”

She said part of the solution also came in better equipping a younger generation of internet users to have the skills to deal with radical content or disinformation when they encounter it online.

Although the U.S. only officially joined the Christchurch Call this year, it had been consistently contributing to the effort, Ardern said.

“Countering the use of the internet by terrorists and violent extremists to radicalize and recruit is a significant priority for the United States,” White House spokeswoman Jen Psaki said in a statement. She also stressed the importance of protecting freedom of expression and “reasonable expectations of privacy.”