NEWKIRK, Okla. -- The U.S. Department of Homeland Security announcement that it was conducting biosecurity drills in the Oklahoma farming town of Newkirk was tucked among the local weekly newspaper's classified ads.

The notice mentioned a "low level outdoor release of inert chemical and biological simulant materials" and directed people to a science-heavy website explaining why the agency chose the community.

The Newkirk Herald Journal thought it should be front-page news, and its subsequent article sent shockwaves through the town of about 2,300 people, leaving them wondering, "Why here?" and questioning the government's assurances about the safety of the chemicals it plans to use during tests that will gauge how authorities might respond to a bioterror event.

"They're trying to tell us it's 100 per cent safe," Brian Hobbs, a 40-year-old construction worker who's helped rally like-minded residents. "It leaves people with an uneasy feeling. I don't want to become the testing ground for the Department of Homeland Security."

About 9,000 wary residents of Newkirk and neighbouring communities, including Arkansas City, Kansas, just across the border, have signed a petition seeking more details from the federal agency. Many residents want guarantees from the government that none of the chemicals will adversely affect nearby cropland, a creek that flows into the Arkansas River or the massive Kaw Lake watershed. Dozens have shown up at community meetings demanding answers.

Newkirk, 161 kilometres northwest of Tulsa, near Oklahoma's border with Kansas, is dotted with churches and modest homes with well-tended yards. A grain elevator at the local co-op is the tallest downtown building. Some here trace their lineage to the Oklahoma Land Rush of 1889, when the area was opened up to white settlement.

"A lot of families have grown up here; it's truly home. That's why everybody's scared," said Newkirk Herald Journal editor Cody Griesel.

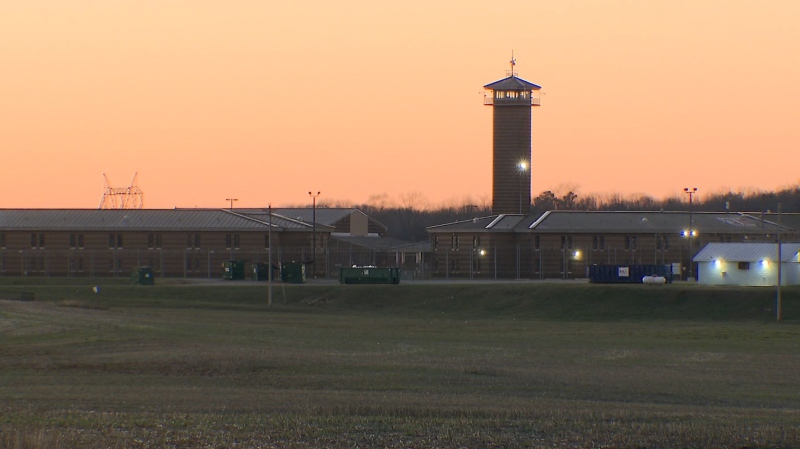

The tests are tentatively set for winter and summer 2018, with no specific dates from the government. The test area is the abandoned Chilocco Indian School campus just outside of town.

Scientists say the cluster of buildings at the site best resemble single-family homes and commercial buildings in any U.S. city. The government said the chemicals will be used to measure the amount of material that penetrates structures in the event of a bioterrorism event, and how authorities can best clean it up in the event of an attack.

The chemicals to be used include titanium dioxide, which is common in sunscreens and cosmetics; fluorescent brightener, found in laundry detergents; and urea, a compound found in urine and fertilizers. The chemical that has probably caused the most worry among residents is called DiPel, a biological insecticide that's been commercially available since the 1970s and is approved for use in organic farming.

Lloyd Hough, the Homeland Security scientist who's overseeing the testing, insists the product is widely used and isn't harmful to humans or wildlife. Hough insists nothing is being kept from residents, and he noted that the government has more time to follow up on their concerns.

"It's not like we're going to show up sometime in the spring and start spraying everywhere," he said.

Kitty Cardwell, a professor at Oklahoma State University and expert in agricultural biosecurity who has been involved in other Homeland Security projects, suggested that some residents may be worried because of the government's involvement in the testing.

"When you hear 'Homeland Security,' it sounds scary ... like quasi-military people running around in hazmat suits -- that seems scary; it seems like a bad science fiction movie," said Cardwell, who added that DiPel is "only bad news if you're a caterpillar."

Those assurances aren't good enough for 59-year-old Alan Newport.

"The thing that really set me off is when they say it's an inert chemical," said Newport, who works for an agriculture trade publication. "It doesn't mean it's safe."