The Search for Ashley and Taylor

The technology we take for granted eases a mother's torment in minutes

Ethan Faber is Managing Editor for CTV News Vancouver. His final dispatch from Sierra Leone is the story of a desperate decision made by a mother 20 years ago in the chaos of war. Join Ethan as he takes up a woman's search for her missing children and discovers how a lack of technology we take for granted is keeping the developing world more isolated than ever. Click here for the CTV News in Africa page to see Ethan's other blogs.

"I did it because I wanted them to be safe," she tells me.

"I did it because I love them."

I’m sitting on a small, handmade bench in the red dirt outside a tiny home in a shantytown high above the capital city of Sierra Leone. As wild dogs chase a rooster and burning trash fills the air with thick, black smoke, Augusta and her family treat me like an honoured guest. She covers the wooden board that serves as a coffee table with an old piece of lace and offers me a mint wrapped carefully in red cellophane. She has high hopes for this visit, but I’m already worried I'll disappoint her. She’s talking about three of her children, triplets - two identical girls and a boy. She hasn’t seen them since they were a year old. That was two decades ago.

I've come here to try to help a friend. Augusta's husband Massa is a taxi driver who's been a great help to me on my first trip to West Africa. We've become close. A few days ago, he asked me a surprising question. "You are from Canada," he said. "Have you heard of a place called British Columbia?" I’m surprised. Few people I’ve met here know anything about Canada, let alone a specific province. When I tell him British Columbia just happens to be my home, Massa stops the car. "You know this place?" he asks, looking at me. I tell him it's the place I was born and raised. "You must meet Augusta," he says. "You must come to our home."

I agree and we turn off a main road onto a rough dirt track heading uphill. The old red and yellow Nissan lurches through giant potholes and climbs over boulders, the oil pan scraping so hard I’m sure we’re going to spring a leak. Massa grins. "Now you see the real Africa."

The home where Massa and Augusta live is essentially a large room made of plaster and concrete. There is only sporadic electricity and no running water, but it's tidy and I can sense the pride.

When Augusta emerges, she's wearing a colourful dress and a serious expression. I sit on the bench. Augusta leans in close and in broken English, she tells me her story. It was the early 1990s. She hadn't met Massa yet and was married to another man. Sierra Leone's civil war was raging. Rebels were burning villages and murdering civilians in a scorched earth campaign and moving steadily north, threatening to sack Freetown. When she gave birth to the triplets, her husband ran away. She was alone, caring for three babies. A year later, the rebels were getting closer. Augusta met a "fixer" from an adoption agency looking to bring children to Canada. The babies were just beginning to walk. Augusta made the hardest decision of her life.

A few years later, the civil war came to Freetown and the rebels ravaged it. Augusta stayed in her home high in the hills and managed to survive. Eventually, the rebels were pushed out of the city and the war ended. She received occasional letters through the adoption agency with updates on her children and their new lives in Canada. Later, she met and married Massa, who'd made it through the attack on Freetown by hiding in a hole he dug with his bare hands and covered with banana leaves. They learned the triplets had been split up. Her son was adopted by a family in the Yukon, while the two identical girls, Taylor and Ashley, were being raised by a family on Vancouver Island. Then suddenly, word of the girls stopped coming. Her son's new family managed to stay in contact, but the girls seemed to disappear and so did the agency. Augusta was cut off.

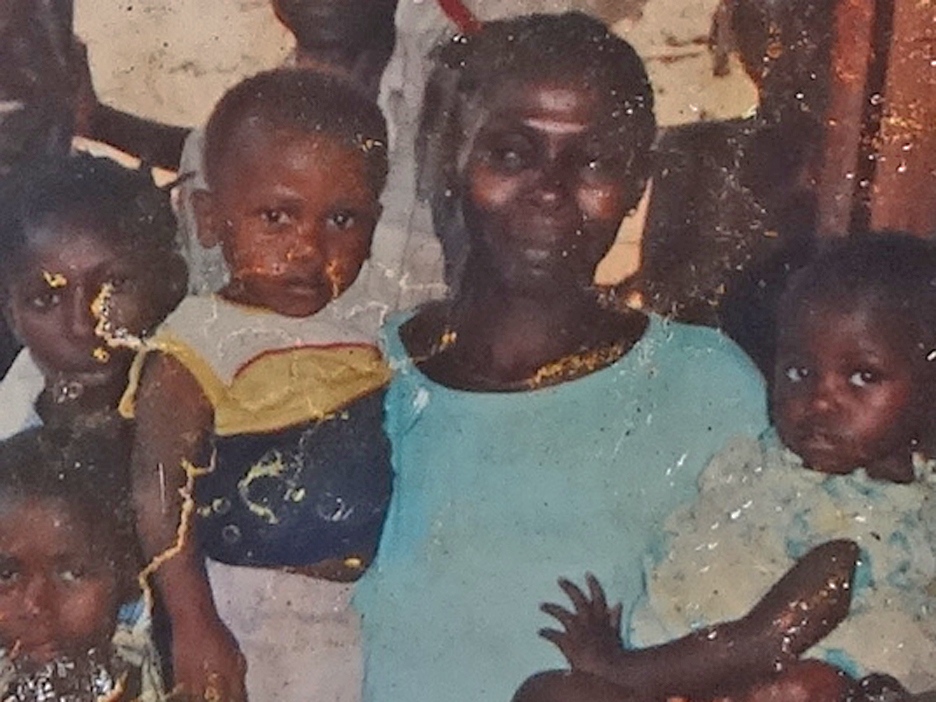

As I sit on the bench, she tells me she can't count how many years it's been since she heard anything about Ashley and Taylor. Then Augusta shows me two clues: the first is a fading picture of the girls. It looks like it was taken in their early teens and we know they are now in their 20s.

The second clue is an old scrap of paper with some names written on it by an adoption agency worker with whom they lost contact long ago. I see the names Taylor and Ashley Zanchet, and at the bottom of the page, the misspelled name of a Canadian province: "British Colombia." This is why I'm here. I am from the mysterious place in Canada where Augusta believes her girls are living. "Do you know them?" she asks, showing me the old picture. I smile and gently explain that British Columbia is a big place with many cities and many people. "Can you find them?" I promise to try.

Later that evening, I return to my hotel and log onto the slow but functional Wi-Fi network. I think about the picture of the girls. They’re young and they live in Canada, one of the top countries on Earth for Internet connectivity. I click on Facebook and type the name Taylor Zanchet. No hits, but there is someone named Taylor Zanchetta. I click on the name and I see the picture. It's a young woman. She's African. Her home is listed as Nanaimo, British Columbia. She looks a lot like the girl in Augusta's fading photograph. Taylor and I are not "friends" on Facebook but I am able to see who she's friends with and one of the names jumps off the screen. Ashley Zanchetta.

Taylor and Ashley.

I click on Ashley’s picture and I see a face that’s almost identical. A few more clicks and I zero in on a woman the girls seem to indicate is their mother. Her name is Cheryl Colombo and she too lives in Nanaimo. I write Cheryl a Facebook message. I tell her I work at CTV in Vancouver but I'm in Freetown for a few weeks training local journalists. I've met a woman named Augusta who is looking for her children. I tell her the names seem to match and I ask if this makes any sense at all. Then I wait.

For the next three days, I hear nothing and I'm forced to deliver the bad news every morning when Massa picks me up and asks. I don't say anything about what I've found on Facebook because I don't know for sure if these are the right girls and I don't know the whole story. I decide it's too risky to get Augusta's hopes up until I hear back. I ask Massa carefully if it's also possible that Augusta's girls don't really want to be found. Perhaps they have made a decision to focus exclusively on life in their adopted country. Massa nods quietly and admits that's a possibility.

"Do you think Augusta understands that?" I ask.

"No way," he says. "She's their mother."

Then, on the third night, there's a message waiting for me on Facebook. Cheryl has written back. "Yes," she writes. "Ashley and Taylor are from Freetown. They were adopted. Their birth mother's name is Augusta Gbanga. Does that sound familiar to you? They now go by the names of Taylor Georgette Zanchetta and Ashley Georganna Zanchetta."

She goes on to say the girls are doing well. They had a phone number for Augusta years ago, but the connection was terrible and never really worked. Cheryl asks me to give Augusta a hug for her. I use my iPhone to take a 'screen grab' image of Taylor and Ashley and the next morning I show it to Massa.

He looks at it carefully and once again, we head to the hills. On the way, he calls Augusta and speaks rapidly in Krio, the local language. I don't need to understand a word to know exactly what he's saying. When we arrive back at their home, Augusta is waiting outside and a small crowd of neighbours has gathered. I sit on the bench and ask Augusta to get out her picture of the girls and I pull out my iPhone. We hold them side by side and there’s no doubt it's a perfect match. Augusta holds my hand and my phone to her chest, then I stand her up and deliver Cheryl's hug.

We embrace for a while without saying anything and that's when it hits me. In just a few minutes on the Internet, I’ve managed to solve a mystery that's been tormenting a mother for years. I realize it's not just a lack of decent roads, electricity and running water that robs people in the developing world of opportunity. The Internet is now also an essential piece of infrastructure. Without it, the poor are more isolated than ever.

A report from the UN tells me that in Sierra Leone, 99 per cent of the people lack regular access to the online community and the knowledge and connections that go with it. Augusta and Massa had never heard of Facebook until I showed them the pictures of the girls. I don't have the heart to tell them that Facebook would make it easy to communicate with them on a daily basis. I don't tell them there are hundreds of millions of people online staying in regular contact with friends and family around the world. There's no point. In the world where Massa and Augusta live, a handwritten letter is the only option.

Cheryl has told me the girls are a little shy, so Augusta decides to send the first letter to her. I take out a pen and a piece of paper and begin to write down Augusta's message to the Canadian woman who raised her children. Everyone involved has given me permission to share this story, so as I sign off from this assignment and try to think of something that will in some way express what I've learned about the courage and resilience of the Sierra Leonean people who have been so warm and welcoming to me, I think it best to give Augusta the last word.

"Dear Cheryl. I am happy and thankful to hear from you. I am happy to hear the children are beautiful and happy. I would like to say thanks for what you have done for them. You are the Canada mother. I would like the children to know why they were adopted. First of all, the father abandoned us. Also, the war was coming and I wanted the children to be safe. I want the children to know I always think about them. I am proud of them because they are in Canada."