LOS ANGELES -- From the beloved opening lines of Leonard Cohen's "Hallelujah" to the rousing, children's-choir conclusion of the Rolling Stones' "You Can't Always Get What You Want," U.S. President Donald Trump's campaign rallies have been filled with classic songs whose authors and their heirs loudly reject him and his politics.

It's become a sub-cycle in the endless campaign cycle. The Trump campaign can hardly play a song without the artist denouncing its use and sending a cease-and-desist letter. Neil Young, John Fogerty, Phil Collins, Panic! At The Disco and the estates of Leonard Cohen, Tom Petty and Prince are just a few of those who have objected.

Campaigns have been turning popular songs into theme songs for more than a century, and American artists have been objecting at least since 1984, when Bruce Springsteen denied the use of "Born in the U.S.A." to the Ronald Reagan reelection campaign.

But this year, the issue has reached an unprecedented saturation point, indicative of a wide cultural divide between the president and his supporters, and overwhelmingly left-leaning musicians, who virtually never make the same demands of Democratic candidates.

"I've been covering this beat for probably 20 years, and this is probably as stark a division I've seen as far as artists not wanting a politician to use their songs," said Billboard contributor Gil Kaufman, who has been covering the convergence of music and politics for the record trade magazine during the campaign. "The choice is so stark for a lot of voters, and it is for musicians too."

Few have objected as adamantly as Young. The fiercely opinionated rock Hall-of-Famer is the rare musician who has gone beyond demands and filed a lawsuit over the repeated use of his songs.

"Imagine what it feels like to hear `Rockin' in the Free World' after this President speaks, like it is his theme song," Young wrote on his website in July. "I did not write it for that."

That feeling that they've been drafted onto Team Trump clearly fuels many artists' anger.

"Their music is their identity," Kaufman said. "It's important to them to not appear as though they are tacitly endorsing Trump."

Other artists have been more befuddled than angry about the playing of songs whose themes are the exact opposite of the messages Trump is sending.

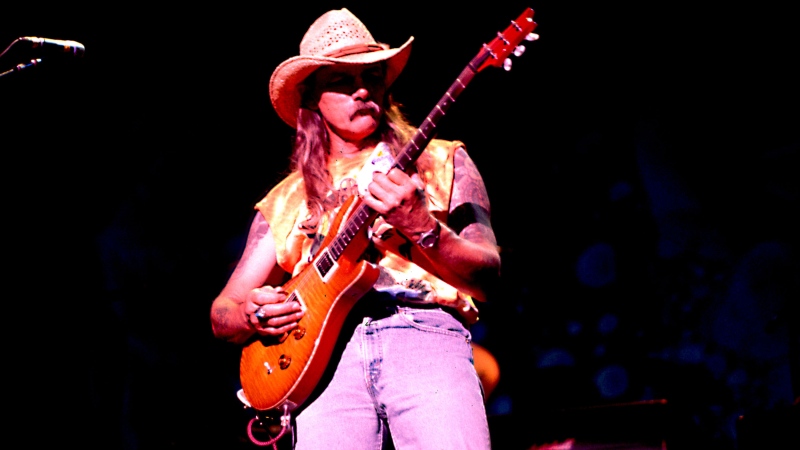

Fogerty said he was baffled by Trump's use of "Fortunate Son," his 1969 hit with Creedence Clearwater Revival, whose condemnation of privileged children of rich men who did not serve in Vietnam sounds like a tailor-made slam of Trump.

"I find it confusing that the president has chosen to use my song for his political rallies, when in fact it seems like he is probably the fortunate son," Fogerty said in a video on Facebook in September.

He was more fiery after he kept hearing it played.

"He is using my words and my voice to portray a message that I do not endorse," Fogerty said in an Oct. 16 tweet announcing a cease-and-desist order.

That the president's rallies are potential spreaders of the coronavirus may be adding intensity to artists' desire not to have their music contribute.

"It's not a great look for the artists, if their music is aligned with something seen as unsafe," Kaufman said.

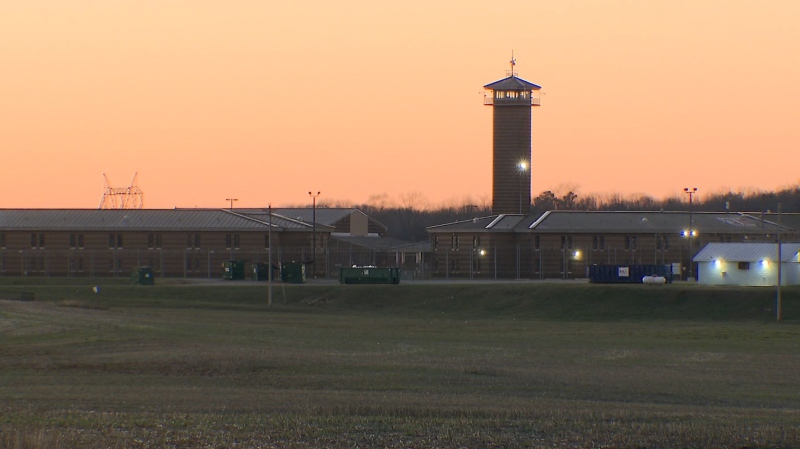

Many social-media observers pointed out that, given its title, Collins' "In The Air Tonight" was especially tone-deaf when it was played at Trump's Oct. 14 rally in Iowa. Collins' attorneys promptly demanded the campaign stop using the song.

Legally, politicians don't necessarily need direct permission from artists.

Campaigns can buy broad licensing packages from music rights organizations, including BMI and ASCAP, that give them legal access to millions of songs

BMI said the Rolling Stones had opted out of inclusion in those licenses, and it informed the Trump campaign that if it did not stop playing "You Can't Always Get What You Want," a Trump favourite in regular rotation at his rallies, the campaign would be in breach of its agreement.

But even if their songs can be played contractually, artists can still object. That usually just means a public demand to the campaign.

"A lot of the time it just takes the cease-and-desist to tell them not to use it, that's already enough for the artist to get their message out that they're not associated with the campaign and did not approve the use," said Heidy Vaquerano, a Los Angeles attorney who specializes in entertainment law and intellectual property.

And there are other legal channels, such as states' right-of-publicity laws, which treat an artists' identity as their property, or the federal Lanham Act, which protects an artist's personal trademark and contains a provision barring false endorsement.

"The use of their music, it could dilute the worth of their trademark," Vaquerano said. "Courts have recognized that that could be an implied endorsement."

The Trump campaign did not immediately respond to a request for comment.

The president has turned more recently to slightly friendlier ground, dancing at events to "Y.M.C.A." by the Village People, whose leader and primary songwriter, Victor Willis, has said he doesn't feel he's endorsing Trump when the song plays.

Yet the campaign cannot avoid condemnation even when playing dead artists.

Petty's widow and daughters, who had been fighting in court over his estate, united in their demand in June that Trump stop using his song, "I Won't Back Down."

Cohen's estate attorneys vehemently objected to the prominent use of "Hallelujah" during the final-night fireworks at the Republican National Convention in August, saying in a statement it was an attempt to "politicize and exploit" a song they had specifically told the RNC not to use.

Cohen attorneys made the rare move of suggesting an alternative, whose title could be taken as a dig at Trump.

"Had the RNC requested another song, `You Want it Darker,"' the lawyers said, "we might have considered approval."