Mother claims non-speaking daughter was secluded, forcibly confined at N.B. school without her consent

If you walked into a room with 14 year-old Lily Hyde, you’d probably hear her giggle before you found her. She’s not your stereotypical, broody teenager who is embarrassed by their parents. In fact, she lights up when she sees her mom Chantelle come in. Lily lives with non-speaking autism and is developmentally around the age of a toddler.

“She's really just a sweet, innocent little thing,” Chantelle said, describing her daughter. “I’ve had other children's parents look at her and say, ‘My God, I haven't heard my child laugh like that in two years…’ but she could look at me 100,000 times in the day and every time, it’s like she hasn't seen me in a week.”

Those joyful moments make up most of their days in Rothesay N.B., but her mom admits, there are times when Lily also loses control.

“When Lily gets highly dysregulated and she's severely distressed, she might try to scratch or, you know, she's bitten me, unfortunately, a couple of times,” Chantelle said.

That has also happened in Lily’s classroom. But Chantelle claims Lily’s dysregulated behaviour at school was kept hidden from her. She did, however, notice that Lily was becoming more aggressive at home, severely shutting down, and even expressing that she didn’t want to go to school.

“She looked at me every morning at the school bus stop, pleading and saying no, but I didn't know what was wrong,” said Chantelle.

That was until another mother from the school told her what she had seen.

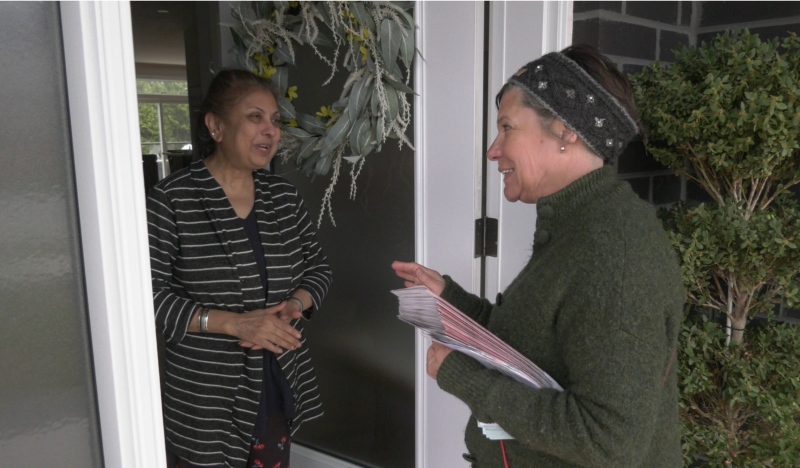

Chantelle Hyde says her daughter Lily’s dysregulated behaviour at school was kept hidden from her. But she noticed Lily was becoming more aggressive at home, shutting down, and expressing that she didn’t want to go to school. (CTV W5)

Chantelle Hyde says her daughter Lily’s dysregulated behaviour at school was kept hidden from her. But she noticed Lily was becoming more aggressive at home, shutting down, and expressing that she didn’t want to go to school. (CTV W5)

“She walked by a room seeing Lily on the inside of a glass window door, screaming and slamming her hands on the window… an adult used their full weight to hold that door closed,” Chantelle explains. She can barely hold back the tears as she describes the incident that she said kept her up at night and shaking for days in disbelief.

“It's really, really hard to imagine how people could do this to such young and vulnerable children.”

Most provincial guidelines state seclusion and sometimes restraints are to be used as a last resort and only in emergency situations. New Brunswick’s Education and Early Childhood Development policy said seclusion should not be used without parental consent. Chantelle Hyde said she never would have allowed it.

“We never discussed, never talked about,” Chantelle said. “They were literally lying to me in front of my face in meetings essentially, if they knew about this and didn't tell me.”

Chantelle said she was left in the dark -- a pervasive problem across Canada, especially for children with disabilities. Informal surveys from B.C., Alberta and Manitoba show hundreds of Canadian parents are learning about their children being secluded or restrained from other parents or peers, not from schools themselves.

It’s not surprising to Guy Stephens, the founder and executive director of the Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint, who is based in Maryland. The Alliance only started three-and-a-half years ago, and has garnered over 20,000 followers online. He started the non-profit corporation after he said his 17-year-old neurodivergent son -- who also suffers from ADHD and anxiety -- was physically restrained, dragged down a hallway and thrown into an empty classroom.

“He had become so traumatized by that, that he didn't want to go back to school. After a lot of soul searching, we ended up homeschooling him for the following two years because he was afraid to go back,” Stephens said.

So Stephens started researching who was affected by these practices. He found seclusion and restraint practices are disproportionately used on both children with disabilities and black and brown children.

“People will lead you to believe it's a 16-year-old with an attitude,” he said. “No, it’s not. That would be the outlier. More often it’s a seven or eight-year-old … that is more easy to control.”

He compares seclusion to solitary confinement - a controversial practice for prison inmates. Stephens claims people resort to restraints and seclusions because they believe it’s the only tool in their toolbox.

“Teachers often believe that it’s the only thing they can do and they need to do it or other children or themselves will be at risk. The truth, though, if you look at data, is that what we find is that teachers and children are more likely to be injured the moment you lay hands on them,” Stephens said.

The Alliance has identified key methods that have worked as alternatives to restraint and seclusion.

Stephens said that children who have already been restrained or secluded will likely experience stress if presented with this kind of technique again. He said this could lead to retraumatization, feeding a vicious cycle in the classroom.

“When kids go into fight or flight mode, barking orders at them is not the answer. You need to help them calm down. Kids - when they get that escalated … they're not able to make rational, logical decisions.”

Aviva Dunsiger is a primary school teacher based just outside Hamilton, Ont. She said when kids become escalated, it can be debilitating to a classroom.

“There would be throwing of things, screaming, particularly with one child who is non-verbal… it wasn’t deliberate behaviour, but it was kind of the reality,” said Dunsinger who at that time, had 31 children in her classroom.

She has taught kindergarten through to grade six for 22 years and has adopted a set of tools that help her navigate outbursts.

“In a classroom environment, it might mean I’m creating different spaces for students looking at what calms individual students. How can we observe where the triggers might be and then respond proactively?”

She notes that while every educator carries with them a different background and experience, a personal concern of hers is that many are unknowingly starting a self-perpetuating cycle.

“If kids are always being removed and punished… that can be a self-fulfilling prophecy. I worry about the kids who would walk in already feeling that stress.”

Back in Rothesay, N.B., Chantelle Hyde is working hard to break that cycle. She’s written to political candidates in the last provincial election, advocating to end the use of seclusion and restraint. And most recently, she’s teamed up with the Alliance Against Seclusion and Restraint to publish a list of resources that help in moving away from the use of these types of techniques.

“An end could be put to seclusion almost immediately without any serious detrimental effects to the people in the situation.”

CTVNews.ca Top Stories

Bodies found by U.S. authorities searching for missing B.C. kayakers

United States authorities who have been searching for a pair of missing kayakers from British Columbia since the weekend have recovered two bodies in the nearby San Juan Islands of Washington state.

Amid concerns over 'collateral damage' Trudeau, Freeland defend capital gains tax change

Facing pushback from physicians and businesspeople over the coming increase to the capital gains inclusion rate, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and his deputy Chrystia Freeland are standing by their plan to target Canada's highest earners.

'It's discriminatory': Individuals refused entry to Ontario legislature for wearing keffiyeh

Individuals being barred from entering Ontario’s legislature while wearing a keffiyeh say the garment is part of their cultural identity— and the only ones making it political are the politicians banning it.

Tom Mulcair: Park littered with trash after 'pilot project' is perfect symbol of Trudeau governance

Former NDP leader Tom Mulcair says that what's happening now in a trash-littered federal park in Quebec is a perfect metaphor for how the Trudeau government runs things.

Saskatchewan households will continue to receive carbon tax rebate: Trudeau

Households in Saskatchewan will continue to receive Canada Carbon Rebate payments, despite the province refusing to remit the federal carbon price on natural gas, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said Tuesday.

'It's just so hard to let it go': Umar Zameer still haunted by death of Toronto police officer

'We hoped for this day, but we were scared that it would not never ever come because it took so long.' That’s what Umar Zameer, the man recently acquitted in the death of a Toronto police officer, told CTV News Toronto in a sit-down interview on Tuesday.

Senate expenses climbed to $7.2 million in 2023, up nearly 30%

Senators in Canada claimed $7.2 million in expenses in 2023, a nearly 30 per cent increase over the previous year.

Canucks goalie Thatcher Demko won't play in Game 2

The Vancouver Canucks will be without all-star goalie Thatcher Demko when they face the Nashville Predators in Game 2 of their first-round playoff series.

Pedestrian, baby injured after stroller struck and dragged by vehicle in Squamish, B.C.

Police say a baby and a pedestrian suffered non-life-threatening injuries after a vehicle struck a baby stroller and dragged it for two blocks before stopping in Squamish, B.C.

Local Spotlight

Mystery surrounds giant custom Canucks jerseys worn by Lions Gate Bridge statues

The giant stone statues guarding the Lions Gate Bridge have been dressed in custom Vancouver Canucks jerseys as the NHL playoffs get underway.

'I'm committed': Oilers fan won't cut hair until Stanley Cup comes to Edmonton

A local Oilers fan is hoping to see his team cut through the postseason, so he can cut his hair.

'It's not my father's body!' Wrong man sent home after death on family vacation in Cuba

A family from Laval, Que. is looking for answers... and their father's body. He died on vacation in Cuba and authorities sent someone else's body back to Canada.

'Once is too many times': Education assistants facing rising violence in classrooms

A former educational assistant is calling attention to the rising violence in Alberta's classrooms.

What is capital gains tax? How is it going to affect the economy and the younger generations?

The federal government says its plan to increase taxes on capital gains is aimed at wealthy Canadians to achieve “tax fairness.”

UBC football star turning heads in lead up to NFL draft

At 6'8" and 350 pounds, there is nothing typical about UBC offensive lineman Giovanni Manu, who was born in Tonga and went to high school in Pitt Meadows.

Cat found at Pearson airport 3 days after going missing

Kevin the cat has been reunited with his family after enduring a harrowing three-day ordeal while lost at Toronto Pearson International Airport earlier this week.

Molly on a mission: N.S. student collecting books about women in sport for school library

Molly Knight, a Grade 4 student in Nova Scotia, noticed her school library did not have many books on female athletes, so she started her own book drive in hopes of changing that.

Where did the gold go? Crime expert weighs in on unfolding Pearson airport heist investigation

Almost 7,000 bars of pure gold were stolen from Pearson International Airport exactly one year ago during an elaborate heist, but so far only a tiny fraction of that stolen loot has been found.