It can seem as odd as it is frightening, how a virus that can be killed with a bit of bleach can be such an implacable and deadly enemy once it gets inside a human body.

There, it invades cells, making replicas of itself that invade other cells, eventually destroying organs and blood vessels. Death is not inevitable. But it is likely.

Right now, the key to fighting Ebola is identifying and then isolating the virus within the people it has infected in order to prevent further spread. That battle is being fought daily wherever the virus appears, primarily in West Africa. The infected are quarantined while they combat the disease, all too often losing.

The other key battle front is being fought by science trying to find a cure. And for a variety of sometimes innocuous reasons, a lab in Winnipeg, Manitoba hasfound itself among the world leaders in the research.

The lab is located in an utterly ordinary looking, medium-sized government building in the north end of the city. A sign outside identifies it as, “The Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health.” But it doesn’t take long before visitors realize, something unusual goes on here.

Our W5 crew arrived about 30 minutes before our appointment in order to take some video of the building’s exterior. In less than two minutes, a man emerged from inside, approached us and ordered us, politely, to stop. He identified himself as security and asked that we erase all video we had taken already. Then we were invited inside to receive a security briefing.

The rules of our visit would be fairly elaborate. Before entering, we would have to have all equipment x-rayed in the same way that is done at any airport departures area. Sections of the building would be off limits, even some sections of rooms could not be shown. And during the entire visit, we would be accompanied by a security employee who would have to see and approve of every image we wanted to take before being recorded. The briefing was good natured, but firm, which came as no surprise considering the nature of the research here, the danger of pathogens getting out of the building, the danger of bio terrorists getting in.

The building contains Canada’s only top security biosafety lab, a level 4 or L4 lab as it’s known where scientists study some of the most dangerous pathogens on earth, Ebola among them. It began back in the late 1990’s when the newly opened lab hired a German born scientist named Heniz Feldmann. Dr. Feldmann just happened to have an interest in Ebola. The second significant happenstance was an almost simultaneous Department of National Defence decision to fund studies into pathogens that conceivably could become terrorist weapons. Suddenly, a Winnipeg lab found itself an important player in the world of viral research.

Already, research at the lab has led to the development of an Ebola vaccine, and a treatment drug called ZMapp. Both are still in experimental stages and are in dreadfully short supply. But the fact they exist at all is a product almost as much of coincidence and circumstance, as it is of brilliant research.

Dr. Gary Kobinger is the lab’s chief of special pathogens. He told W5, “People who were here at the beginning had a concept that was very, very important for creating this amazing environment for scientific research. We’re not a massive operation with the resources that some Level 4 labs have, for example in the United States. But we are making breakthroughs.”

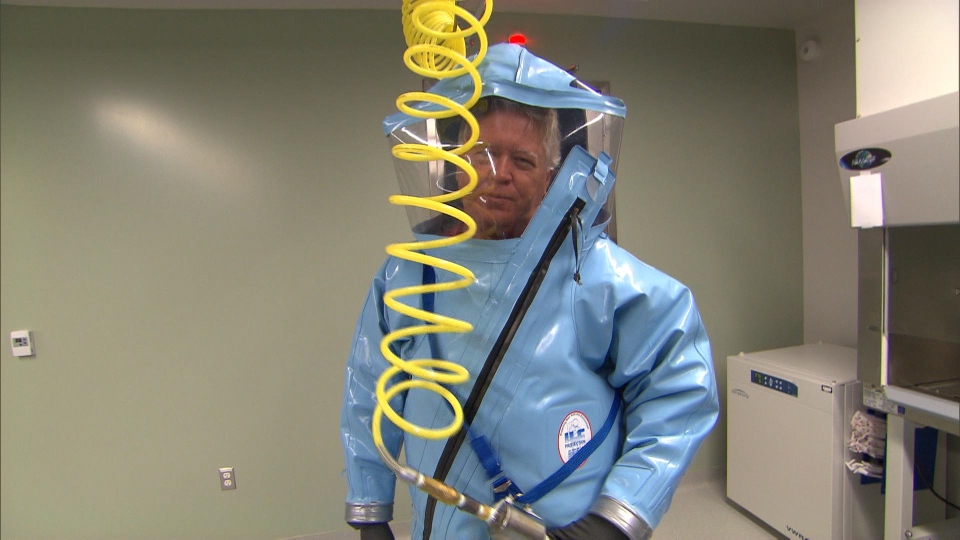

W5 is given a demonstration of the kind of safety precautions needed for such research. To work with Ebola, you must first strip off all street clothes and don what are called, sweats. Then into a special room where you must dress in a large and completely sealed suit that closely resembles something an astronaut might wear. Once suited up, you plug in a respirator that supplies air and maintains a higher than room pressure to prevent any, even microscopic penetration from the outside. Then through air locks and into the lab where Ebola is handled.

We are allowed to watch through a window only, a room where three researchers, barely recognizable in the bulky safety suits, were testing samples taken from Ebola infected animals. The purpose of this particular study is to try to understand why the particular strain of Ebola now spreading from a terrorized West Africa, is so deadly.

“The strain is a little bit different than what we’re used to seeing,” explained Dr. Kobinger. “It’s just three percent different. It doesn’t sound like much but we have to know why, and to make sure that vaccines and treatments being developed will be good.”

Beyond research, the lab has made a second contribution to the fight against Ebola that arguably in the short term, is even more important. In order to combat the virus and isolate its carriers, it must first be identified. And for that, the lab has developed a tool that can be taken into the field, and used to test blood samples for Ebola. Already, there is one being used in Sierra Leone.It is called a mobile lab, and at first glance, it looks like a large, transparent plastic box that would fit on a desk or the end of a kitchen table. A closer look shows it is considerably more elaborate. There are two large holes with sleeves projecting inside the box which is sealed. A tester can slide arms into the sleeves that will provide protection from the blood sample sitting inside.

Allan Grolla who works with the Winnipeg facility, demonstrated to W5 how it works. There are a series of procedures and manipulations of the sample that have to carried out, and with each step, there is an elaborate over-riding preoccupation with avoiding any contact. “All tips, anything that touches liquid inside the mobile lab will be rinsed with bleach to kill anything that’s there. And then it’s discarded,” he said. “All of the waste product then is burned in the field. So everything is killed twice in the handling.”

For weeks now, the Ebola crisis in West Africa has been overwhelming medical facilities.

By now, the images of people dying in the streets or at the entrances to hospitals that can take no more patients have horrified viewers around the world. All experts have said that they need more help on the ground, and they need the capacity to diagnose quickly people they believe are carrying the virus.

It is why the Winnipeg facility sent its mobile lab and two scientists who staff it daily. One of them, Dr. Cindi Corbett, happened to call the Winnipeg Operations Centre while we were visiting. She told W5, “There are some good days. Today for example, we just released an 8 year old girl who tested negative. It was just a happy moment.” But when pressed, she also spoke of what they experience constantly, so familiar to medical teams trying to deal with the crisis. She said, “We had a family come in and the children remained negative for a few days and then after they finished the incubation, they tested positive. It is just heartbreaking.”

Ebola is not an automatic death sentence for everyone who catches it. But the World Health Organization has said, the average death rate in the present crisis is about 50 percent. It is one of the deadliest pathogens known to science, and for now, it is winning the battle against those trying to stop it.

Arrayed against it, a growing army of health workers on the ground in west Africa, and science. And thanks to decisions taken more than a decade ago, a lab in the north end of Winnipeg now finds itself at the front line.