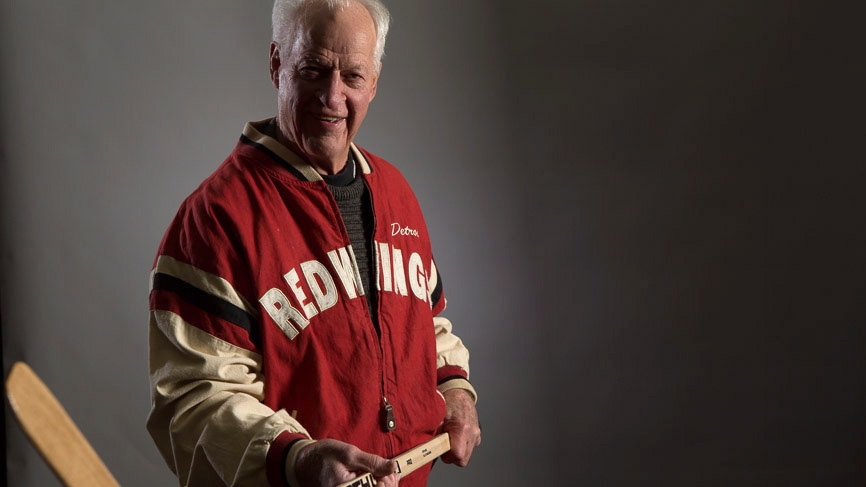

EDITOR'S NOTE: "Mr. Hockey: My Story," a new book by Gordie Howe, hits the shelves Oct. 14. The 86-year-old Howe, who has a form of dementia, is not doing media interviews to promote the book. However, publisher Viking has provided exclusively to The Canadian Press the text of a Q and A between Howe and Wayne Gretzky, which was conducted by email in September. A close friend of the Howe family, Gretzky wanted to be involved in the book's release. Gretzky and an editor at Viking worked together to come up with the questions for the interview -- the only one Howe will do to promote the book. Marty Howe, Gordie's son, transcribed his father's answers.

WAYNE GRETZKY: In your memoir you write about participating in the puck-drop ceremony for the 2014 Winter Classic alumni game at Comerica Park. Could you tell me a little bit about playing outdoors as a child? What was your local rink like? What's your fondest memory of playing outside?

GORDIE HOWE: I loved playing hockey and looked forward to getting on the ice. If I wasn't home eating I was on the ice skating all winter. The rink was just boards and ice. In the Depression there was no money to do much -- I think we were lucky there was man-made ice to skate on. I don't know that any memory stands out as the fondest, but I always liked to score and loved to win. That was what I lived for.

WG: Having mentored countless younger players, you are one of the most iconic father figures in the hockey world. You're also known for a mischievous streak and the chip on your shoulder. What's the piece of advice you've imparted that kids aren't likely to have heard from their teachers or other authorities?

GH: One of my rules was to do unto others before they do unto you, but that was never my first advice to youngsters. What I always started with was making sure they held their stick in the proper position. You should hold the top hand on the stick like you would hold a hammer when you're driving a nail. You have the most leverage and you won't get your wrist broken. The chip on my shoulder was earned over many years of hard knocks and each player has to earn that chip on their shoulder their own way.

WG: Gordie, your book discusses the evolution of the game. Obviously a lot has changed since you played your last shift in the 1980s, never mind your first shift in the '40s. What are the best and worst changes?

GH: The best change was when they got rid of the curved steel at the bottom of the back of the net and replaced it with padding. The curves met in a point, and many players were injured over the years by sliding or crashing into the net. Mark (Gordie's son) was pretty much impaled by this portion of the net. His injury was so serious the nets were changed shortly after.

WG: Your wife, Colleen, is probably the most famous hockey wife (and mother) in history, and you refer to your mother as the strongest person you've ever known. They both lived amazing lives. What do you admire most about each of these incredible women?

GH: Colleen and my mother were both hard-working, both very determined, giving of their time to help others and above all dedicated to their family. That meant they could be incredibly generous. It also meant that they could be pretty formidable when they were looking after their family's best interests. You didn't mess with either one of them. If everyone were as tough, as honest, and as warm as those two, the world would be a better place.

WG: These days, talented kids are encouraged to specialize, playing hockey and training year round. Both you and Bobby Orr talk about the importance of playing a variety of sports and having fun doing it. Do you think this advice is lost on today's kids? Is the game suffering for it?

GH: I still believe it is important that children have a chance to play other sports, because they all offer learning experiences. Soccer is a growing sport and would be a good complement to hockey. I played a lot of baseball and golf over the years. They both need good eye-hand co-ordination, not a bad thing for a hockey player. But more importantly, I'd hate to have missed out on all those friendships and victories. In fact, one of my regrets is giving up baseball in the off-season. With both parents working in most families now there seems to not be enough time to get involved in several sports. I don't think the game of hockey suffers from this but the children do miss out on some great life experiences.

WG: You did a lot of things that other people can't do -- one thing I've never seen is a hockey player who could score right- and left-handed. Are you ambidextrous?

GH: I have always been able to do most things left- or right-handed so I guess I am ambidextrous. I don't really think about doing things right- or left-handed, it just happens. If I was going around a player I would automatically move my stick to the side away from the defender to protect the puck better. There is no time to think about something like that in the middle of a hockey game. You just do it.

WG: You got your start in the Original Six, then played through the expansion years and a merger with the WHA, where the league grew to 21 teams. Did you notice a change in the quality of the game over the course of your career? Talk of expanding the league to Seattle, Quebec City and Las Vegas has been big news in recent months. Do you think today's talent pool is deep enough to support three or four new teams?

GH: The Original Six had more depth in the talent pool, no doubt about it. There was more than enough talent to go around. There were eight players with NHL talent that could take your place if given the chance. So no one wanted to be out of the lineup, even if they were hurt, because the guy who stepped into your roster spot was likely good enough to keep it. Knowing that really pushed players. No one took a shift off, that's for sure, and it made for a pretty intense game. At the same time, I think there are still plenty of players out there with a new crop developing each year. The talent pool has also expanded to Europe in a big way. There is definitely enough talent for expansion. I did notice a change in the game after expansion. The game became more offensive-minded, increasing scoring, which probably means that elite defencemen are hard to come by. But fans don't mind seeing goals.

WG: We both made the jump to professional hockey at a young age, and you mention in your book that junior hockey didn't go exactly as you had expected it to. There's been a lot of debate lately about the relative benefits of the CHL versus the NCAA, largely centred on a junior team's responsibility to prepare players for a life and career beyond the rink. If you were making the choice now, which route would you go?

GH: I would go where the most talent is. Where I could play the most games. I never thought of doing anything but play hockey and this will never change for me. If I had to do it again I would I would still go the junior hockey route but that is me. It is different for everyone and each of us has to decide what is best for themselves. I would say it is important to have a good education as hockey is a career that does not last many years and you need to be prepared for this. It is also important to network with people you meet in life. There is the old saying it's not what you know it is who you know.

WG: One difference between the game today and the way it was played when you were an annual all-star was that you played in an era ruled by a more straightforward "code." You and other superstars mixed it up and watched your own backs. What do you think of the modern NHL's pests, who slow the game down and try to draw penalties?

GH: There were not many pests in the old days because you had to back up the words that came out of your mouth. If you couldn't back up your words you wouldn't last very long. I never said a lot on the ice but when I did I meant it.

WG: Wearing No. 9 in the NHL is considered an honour. (That's the number I wanted when I went to junior. They didn't give it to me, though.) What has No. 9 meant to you?

GH: It's a pretty classic number, and a lot of great players have worn it, but what it meant to me was that I got a better night's sleep. Many people may not know that my first number with the Red Wings was No. 17 until early into my first season. The No. 9 became available and it was offered to me. We travelled by train back then, and guys with higher numbers got the top bunk on the sleeper car. No. 9 meant I got a lower berth on the train, which was much nicer than crawling into the top bunk.

WG: You've notched two "Gordie Howe Hat Tricks," scored 975 goals, 1,383 assists and spent more than 2,000 minutes in the penalty box. Could you tell me about your most memorable goal, assist and fight?

GH: The goal to pass Rocket Richard's record was a milestone goal. At the time the pressure was on me and my teammates until I finally scored. It is funny how you can put so much pressure on yourself when it is really just another goal. The Lou Fontinato fight was the one that most will always remember including myself. Lou and I didn't like each other much back then, and that wasn't the first time our paths crossed. We did respect each other, though, and I am proud to say that Lou and I became friends years later.

WG: In head-to-head action, WHA teams did great against NHL teams. In your view, did players from the younger league have something to prove or did they play a different style?

GH: You probably saw things the same way, but to me the WHA was more offensive-minded than the NHL. Some might say it was wide open at times. The WHA also had quality veterans for leadership and a great group of young talent just coming into their own when the leagues merged -- but you would know that. Traditionalists may have been surprised that those teams did so well against NHL squads, but the guys in the dressing rooms weren't.

WG: A lot of WHA teams played in non-traditional markets, where fans knew little about the game and teams tried all sorts of unusual gimmicks to fill their rinks. We saw some pretty interesting things back then. What was the strangest thing you saw in the league?

GH: There were blue pucks, white skates and unlimited curves on sticks but the one thing I remember most was the first nickel beer night at one of our home games in Houston. There were more fights in the stands than there were on the ice. The fans even jumped out of the stands to fight the referees as they left the ice between periods. I had to go across to the referees' locker-room and ask them to finish the game, promising it would not happen again. Funny we didn't get any penalties in the third period.

WG: You are unique in that you played hockey at the highest level with your sons. As you make clear in your book, hockey is a tough game. Did you ever have to step in to back up Mark or Marty or both?

GH: The boys could take care of themselves but if I thought there was a dirty play or hit I would always deliver some of my own pain and make sure people would think twice about doing that again. What father wouldn't?

WG: I am on record as saying that you're the greatest hockey player of all time, and some other pretty good players, including Bobby Orr, have said the same thing. Over the years, people have always said that if you hadn't played hockey, you could have played major league baseball. In your opinion, who was the greatest baseball player ever?

GH: There are so many but Al Kaline was a close friend of mine and I will put him in my best group. Over 3,000 hits, 18 all-star games, and an all-round great guy.

WG: When you came into the league, even star hockey players were regular guys -- usually small-town Canadians who knew a thing or two about manual labour. Now, thanks to media exposure and much larger salaries, they are celebrities. Do you think something has been lost?

GH: Hockey players as a group are still small-town boys. They are the most approachable group of athletes you will have the pleasure of meeting, as you know. But yes, things are different today, though I don't think it's the players. The difference today is the travel, the way the buildings are designed. The players are so tightly scheduled that their lives are totally focused on hockey. They charter out to the next city right after the game and may not get there until 1 or 2 a.m. They have a 1 p.m. pre-game skate, eat and take a short nap and get to the rink for the game. Not a lot of time to spend doing anything else. The arenas are built now with no access to the players unless you are with the press. The old rinks used to have you walking through the fans to the ice. It was interesting at times, though fans are generally respectful and decent, every once in a while someone would want to get into it with a player. Still, I do think something is lost when the players are cut off from the fans. In the end, players and fans all love the same thing about the game.

WG: Reading your book, it's clear that you got away with a few things behind the play that guys today would get called for. Do you think your relationship with the referees would be different if you were playing today?

GH: The biggest difference is today there are two referees instead of one. A lot of things would happen behind the play because the referee is following the play up ice and it is hard for him to see what is going on behind him. If you wanted to send a guy a message, you just had to be smart enough to wait until the ref was focused on something else. You just had to wait for the right moment. And you might have to wait a long time. Anyway, that is why things would happen behind the play. Today you could never get away with the things we did.

WG: You played the game for decades without a helmet. Though you did have a couple of serious injuries, that is still a remarkable streak. Today, a player without a helmet might not make it through a single game without a head injury. Do you think that says something about respect between players in the NHL today?

GH: It seems there could be a lack of respect amongst players but I think the game is just very competitive. The obstruction rule changes, stopping the hooking and holding has made the game much faster, and probably more dangerous. The equipment is much more protective with more hard plastic that can be used as an offensive weapon when checking someone. Players nowadays turn their backs to you when you approach to check them. This is something we would never have done. You were taught never to turn your back on a checker, as you end up going face-first into the boards. You can end up with stitches, lost teeth, separated shoulders or much worse like neck or back injuries. With the cycling of the puck and trying to draw penalties turning your back to the play is the norm now. The other thing is in the middle of the ice guys skate with their heads down or looking behind them as they cross the ice waiting for a pass. This is a good way to wake up on the ice with the trainer staring down at you. With the new rules players are not expecting to get hit in the centre-ice areas, which makes them more vulnerable. Still, I see that a lot of the time, the defensive team passes up these hits, maybe even the majority of them. That tells me there is still respect between players.

WG: For me, it was always an honour to be asked to help out Team Canada any way I could, something I was able to do a number of times. For various reasons, you had that opportunity only once (though you were missed in 1972). What did it mean for you to play for Team Canada in 1974?

GH: It was great to play for Team Canada in '74. It gives you a sense of pride to compete for your country, and I would have loved to be there in '72, but I was retired. I wish I had more opportunities to play for Canada when I was younger, but pros just never had the chance in those days. It was just set up that way. It was the amateur players who went to the Olympics and world championships back then. I can't complain though. I finally got my chance, and we gave the Russians a good fight.

WG: You're quick to acknowledge the selfless generosity of the many friends and neighbours who helped you on your way to a legendary hockey career. Who gave you the biggest push?

GH: It was not just one person that made the difference. I have to start with my mother, my coach in school hockey, my friend Frank Shedden's father, who gave me Frank's hockey equipment when Frank got too sick to play. There were even NHL players who lived in Saskatoon that would talk to you with encouraging advice, made me think I had a real chance. I wanted to play hockey in the big league so bad and I pushed myself to be as good as I could be. I just wanted to be on the ice all the time. Looking back, I was obsessed at times. I got exactly what I dreamed of, which makes me a very lucky guy. I am incredibly grateful to everyone who helped me along the way. You don't get to fulfil that dream without a lot of support.