Pop quiz: Who won the Stanley Cup 100 years ago?

If you don’t know the answer, don’t take a guess. You’ll be wrong.

The correct answer, as diehard hockey fans know, is that 1919 was the only year a Stanley Cup final was called off after it began – meaning there was no winner.

Just months after the end of the First World War, which saw many of the top players leave the game behind for military service, the professional hockey world was facing a new threat: influenza.

“This flu was particularly bad. It’s not like ‘Gee, guys, got the sniffles.’ This was something people died from,” hockey historian and author Eric Zweig told CTVNews.ca.

A Spanish flu pandemic started sweeping the world in 1918. By the time it ended more than two years later, it had infected an estimated 500 million people – about 30 per cent of the world’s population – and killed at least 50 million. There were approximately 50,000 deaths reported in Canada, and at least 500,000 in the United States.

Given those numbers, it might not be surprising that some of the world’s best hockey players at the time would also fall victim to the disease.

The Montreal Canadiens and Seattle Metropolitans started their battle for the championship on March 19, 1919. Thirteen days later, with the deciding Game 6 hours away, the game was abruptly cancelled because several players from both teams were in hospital with the flu. The illnesses were serious enough that there were concerns Montreal would not even be able to put six players on the ice.

“You can’t trust all the reporting from that era, but it’s said that even with the players sick, the Canadiens wanted to borrow players from the Victoria team and finish the series – and the Seattle guys said ‘No, that’s not fair to you,’” Zweig said. There are also stories that suggest Montreal tried to forfeit the series, only to be told that Seattle wasn’t interested in winning the Cup on a forfeit.

In the end, the series was never completed. It was the first year without a Cup winner since the trophy was created – and remained the only winner-less year until a lockout of NHL players wiped out the 2004-05 season.

The Cup itself, which in those days was inscribed only with the name of each year’s winning team, was symbolically left blank.

It’s a heck of a story. It’s also one which might have caused eagle-eyed hockey fans to raise an eyebrow at some of the facts in the preceding paragraphs.

Wait a minute, they might be asking, how could a Game 6 be winner-take all? Why was Seattle, which has never had an NHL team, playing for the Stanley Cup? And what happened to that empty spot on the trophy?

Read on to find out.

ROAD TO THE CUP

The Stanley Cup wasn’t always tied to the NHL, as it is now.

In fact, Lord Stanley commissioned the trophy 25 years before the league was created, with the intention that it would be awarded to the best amateur hockey players in Canada.

The Cup was initially a challenge championship, meaning any team that won it would have to hold onto it and defend it against all comers. While there were criteria restricting Cup challenges to teams that stood a realistic shot at winning it, teams from smaller cities such as Kenora, Ont. (then known as Rat Portage), Brandon, Man., and Dawson City, Yukon, were able to play for the trophy during this era.

By the mid-1910s, with professionalism starting to take hold in major hockey markets, the rules were rewritten so that the only teams eligible to play for the Cup were the champions of the National Hockey Association (which was replaced by the NHL in 1917) and the champions of the Pacific Coast Hockey Association.

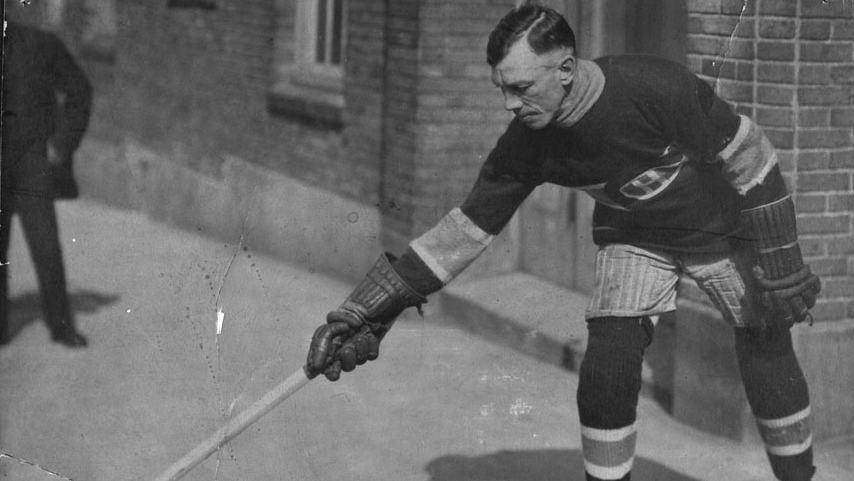

This is how Montreal and Seattle came to meet in March, 1919. Both teams had multiple future Hall of Famers on their rosters, including Seattle star Frank Foyston and Montreal player-coach Newsy Lalonde. In goal for Montreal was Georges Vezina – the namesake of the Vezina Trophy awarded to this day to the NHL’s top goalie of each season. Opposing him for Seattle was Hap Holmes, who Zweig argues was every bit as good between the pipes as Vezina.

Seattle was, however, without the services of their team captain. Bernie Morris had led the Metropolitans to victory over Montreal in the Stanley Cup two years earlier, but was unable to take part in the 1919 series because he had been arrested for draft-dodging in the U.S.

“If he played, it would have been enough of a difference that Seattle might have won it [before the flu hit],” Zweig said.

The loss of Morris didn’t seem to be a big obstacle for the Metropolitans, as they took the opening game 7-0. Montreal and Seattle traded wins over the next two games, and Game 4 ended in a scoreless tie after two overtime periods. Game 5 also went to overtime, where Montreal scored a goal to tie the series at two games apiece – where it would stay, forever unfinished.

HOCKEY IN 1919

Hockey players in 1919 used sticks to shoot the puck toward the net, where a goaltender would try to keep it out. Teams played with five skaters and one goalie on the ice at a time. Physical contact was allowed, but players who committed serious violent acts were sent to the penalty box for a few minutes of penance.

Beyond that, though, the version of hockey played in 1919 contained some quirks which might surprise modern fans.

“People will tell you ‘Oh, you’d hardly know the game.’ In many ways, you wouldn’t,” Zweig said.

One of the most noticeable differences is that team rosters comprised far fewer players than they do today. Current NHL teams are allowed to dress 20 players per game. Teams 100 years ago typically used about half that number, meaning individual players spent far more time on the ice.

“You’d have to pace yourself more to get through an entire game,” Zweig said.

“No one went all-out for a 30-second shift and then hit the bench and let two or three more lines roll out there.”

Players wore far less protective equipment in those days. There were no helmets – not even goalie masks. But the danger level was also lower, because hits weren’t delivered with as much force today and shots weren’t as hard as they are today.

“It would look more like guys playing shinny in their local rink than it would look like NHL hockey to us these days,” Zweig said.

Forward passing had just been introduced to the game, although it was only allowed between the two blue lines, meaning stickhandling and puck-carrying were extremely valuable skills.

Each league operated under its own set of rules. During the Stanley Cup, teams would alternate, playing one game under PCHA rules and the next under NHL rules. The games in 1919 were typically close when NHL rules were used and one-sided Seattle wins when the PCHA rulebook was in effect, leading Zweig to suspect that Seattle was likely the more talented team overall, rule differences aside.

The biggest difference of all may have been in following the game. Newspaper coverage was often the best way for fans who couldn’t attend games themselves to follow their teams, as radio broadcasts were still years away and television had yet to be invented.

AFTERMATH

Four days after the Game 6 that was never played, Montreal defender ‘Bad’ Joe Hall died in hospital from pneumonia. Influenza was considered a direct contributing factor. Popular with fans for his rough-and-tumble style, Hall would go on to be enshrined in the Hockey Hall of Fame.

The rest of the players recovered from their illnesses. Seattle returned to the Stanley Cup the following year, losing to Ottawa in five games. Montreal wasn't back until 1924, but went on to win more Cups than any other team, past or present.

The blank space on the trophy disappeared in 1948, when the names of both teams and the phrase “series not completed” were engraved to fill the 1919 slot.

The PCHA merged with a rival league to form the Western Hockey League. The merged league disbanded after the 1926 Stanley Cup, at which point the NHL became the sole top-level professional hockey league in North America and took control of the Cup.

Infectious diseases continued to attack NHL players from time to time. One of the most recent notable cases was a mumps outbreak that affected several teams in 2017.

While no illnesses have hit hard enough to cancel the Stanley Cup, it’s not out of the question that it could happen. The world has not seen a global pandemic as serious as the Spanish flu since, and the World Health Organization has warned that a major pandemic is inevitable.