American millionaire Jonathan Lehrer denied bail after being charged with killing Canadian couple

American millionaire Jonathan Lehrer, one of two men charged in the killings of a Canadian couple in Dominica, has been denied bail.

A microscopic organism survived 24,000 years in Siberian permafrost and lived to reproduce, according to a Russian study.

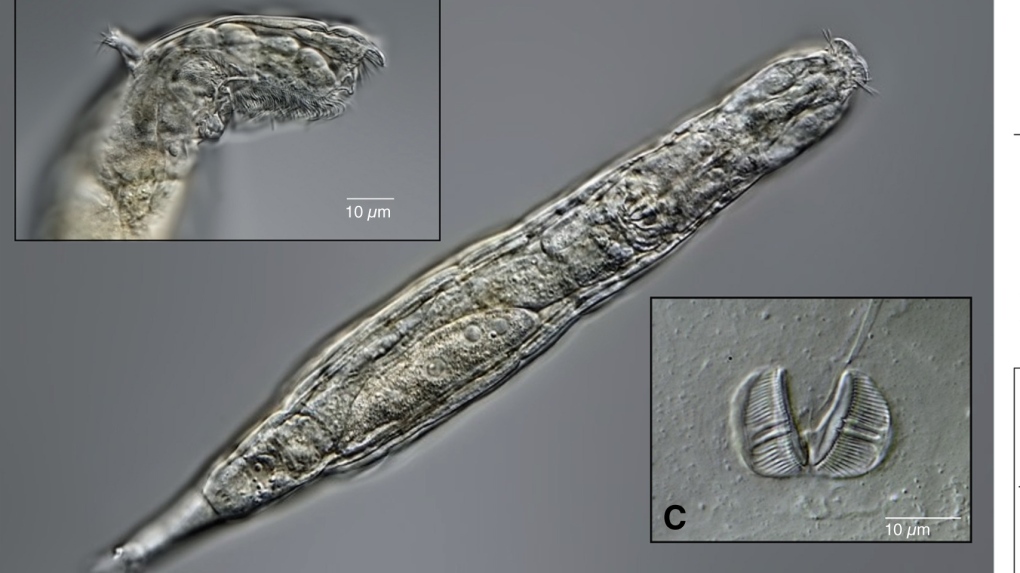

Bdelloid rotifers are known for their ability to survive, particularly in unwelcoming environments like extreme cold. They are typically found in freshwater habitats all around the world.

The tiny multicellular animals were found when researchers collected samples 3.5 metres below the ground surface of Siberian permafrost.

Once thawed, the rotifers were able to reproduce, despite being frozen for millennia. The tough little animals are an entirely female species that reproduce asexually.

Cryo-freezing has been the focus of much science fiction. Now these tiny rotifers could shed some light on the process. Prior to this research it was thought that bdelloid rotifers could survive up to 10 years when frozen.

"The takeaway is that a multicellular organism can be frozen and stored as such for thousands of years and then return back to life -- a dream of many fiction writers," Stas Malavin, co-author and scientist at the Soil Cryology Laboratory at the Institute of Physicochemical and Biological Problems in Soil Science, said in a press release.

To better understand the process, researchers froze and thawed rotifers and found that they were able to remain undamaged from ice crystals that form during slow freezing, suggesting some sort of mechanism to protect their organs and cells from damage caused by extremely low temperatures, according to the release.

While cryo-freezing may not yet be a possibility for humans and other mammals, it’s a step in the right direction.

“Of course, the more complex the organism, the trickier it is to preserve it alive frozen and, for mammals, it's not currently possible,” said Malavin. “Yet, moving from a single-celled organism to an organism with a gut and brain, though microscopic, is a big step forward."

American millionaire Jonathan Lehrer, one of two men charged in the killings of a Canadian couple in Dominica, has been denied bail.

Cabinet minister Dominic LeBlanc says he plans to run in the next election as a candidate under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's leadership, amid questions about his rumoured interest in succeeding his longtime friend for the top job.

A male columnist has apologized for a cringeworthy moment during former University of Iowa superstar and college basketball’s highest scorer Caitlin Clark’s first news conference as an Indiana Fever player.

Health Canada will change its longstanding policy restricting gay and bisexual men from donating to sperm banks in Canada, CTV News has learned. The federal health agency has adopted a revised directive removing the ban on gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men, effective May 8.

The United States has vetoed a widely backed UN resolution that would have paved the way for full United Nations membership for the state of Palestine.

Bayer announced Thursday it is recalling two lots of its hydraSense Baby Nasal Care Easydose due to a potential contamination.

Technology from the 19th century has been brought out of retirement at a Newfoundland gardening store, as staff look for all the help they can get to fill orders during a busy season.

Kevin the cat has been reunited with his family after enduring a harrowing three-day ordeal while lost at Toronto Pearson International Airport earlier this week.

A group of suspects that allegedly defrauded seniors across Ontario and other parts of Canada using a so-called emergency grandparent scam appear to have ties to 'Italian traditional organized crime,' according to an investigator involved in the OPP-led probe.

Kevin the cat has been reunited with his family after enduring a harrowing three-day ordeal while lost at Toronto Pearson International Airport earlier this week.

Molly Knight, a grade four student in Nova Scotia, noticed her school library did not have many books on female athletes, so she started her own book drive in hopes of changing that.

Almost 7,000 bars of pure gold were stolen from Pearson International Airport exactly one year ago during an elaborate heist, but so far only a tiny fraction of that stolen loot has been found.

When Les Robertson was walking home from the gym in North Vancouver's Lower Lonsdale neighbourhood three weeks ago, he did a double take. Standing near a burrow it had dug in a vacant lot near East 1st Street and St. Georges Avenue was a yellow-bellied marmot.

A moulting seal who was relocated after drawing daily crowds of onlookers in Greater Victoria has made a surprise return, after what officials described as an 'astonishing' six-day journey.

Just steps from Parliament Hill is a barber shop that for the last 100 years has catered to everyone from prime ministers to tourists.

A high score on a Foo Fighters pinball machine has Edmonton player Dave Formenti on a high.

A compound used to treat sour gas that's been linked to fertility issues in cattle has been found throughout groundwater in the Prairies, according to a new study.

While many people choose to keep their medical appointments private, four longtime friends decided to undergo vasectomies as a group in B.C.'s Lower Mainland.

Adineta sp. isolated from permafrost, site of sampling, results of bioinformatics and experimental procedures. (A), (B), and (C) taken on a Canon Eos 600-D APS-C camera under a modified Reichert Diastar microscope with Zeiss planapo DIC optics and custom-built flash. Images were post-processed in Adobe Photoshop ® for contrast and color balance. (Credit: Lyubov Shmakova, Stas Malavin, Nataliia Iakovenko, Daniel Shain, Michael Plewka, Elizaveta Rivkina)

Adineta sp. isolated from permafrost, site of sampling, results of bioinformatics and experimental procedures. (A), (B), and (C) taken on a Canon Eos 600-D APS-C camera under a modified Reichert Diastar microscope with Zeiss planapo DIC optics and custom-built flash. Images were post-processed in Adobe Photoshop ® for contrast and color balance. (Credit: Lyubov Shmakova, Stas Malavin, Nataliia Iakovenko, Daniel Shain, Michael Plewka, Elizaveta Rivkina)