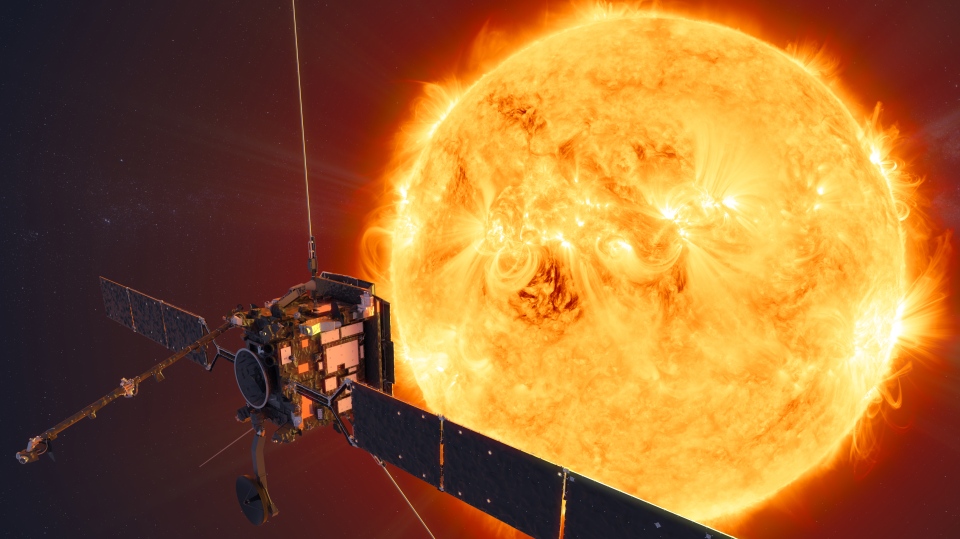

TORONTO -- A new spacecraft set to launch this weekend is going to be travelling closer to the sun's poles than ever before on a special mission to photograph the star, according to NASA.

The Solar Orbiter probe will be setting off Sunday with the aim of capturing the first images of our sun’s north and south poles.

The mission, run in collaboration with the European Space Agency (ESA), is aimed at learning more about solar winds, according to Paul Delaney, professor of Physics and Astronomy at York University.

“Solar wind is basically charged particles that are streaming off the sun throughout the solar system,” he explained on CTV’s Your Morning Friday.

While solar winds can give us sights such as the aurora borealis -- also known as the Northern Lights -- it’s not always beautiful when they interact with the Earth and the Earth’s magnetic fields. If a gust of solar wind becomes less of a wind and more of a gale, Delaney said, these charged particles are capable of overwhelming our satellite systems.

Satellite systems are responsible for GPS, cellphone service, TV signals and even search and rescue coordination, so it’s no small matter if a satellite is impacted by solar winds.

The winds can also create dangerous conditions for astronauts in orbit, “or future space tourists,” he pointed out.

The ultimate consequence is a geomagnetic storm like the ones in 1989, he said, which knocked out “power grids across the planet.

“You take out the satellites of this planet, and yours and I’s lives would be very different. You’d be thrown back 100 years. Personally, I like my current existence of technology.”

But it’s not easy to get a probe close to the sun’s poles.

“Most of the probes that we launch in our solar system stay in what we call the ecliptic plane – so in the same plane that the Earth orbits around the sun,” Delaney explained. “To get out of that plane requires a lot of energy.”

In order to build up that energy, the probe will be using Earth and Venus as a sort of “catapult.” By slingshotting around the two planets, over and underneath the sun, the Solar Orbiter will be able to use them “as a gravitational anchor,” to pull itself closer to the sun.

The mission will take seven years, according to a NASA press release. At its closest pass by the sun, the spacecraft will be within 42 million kilometres of the surface -- and while that might sound like a vast distance, the Earth is roughly 147 million kilometres from the sun, meaning the probe will be around three times closer to the star than we are now.

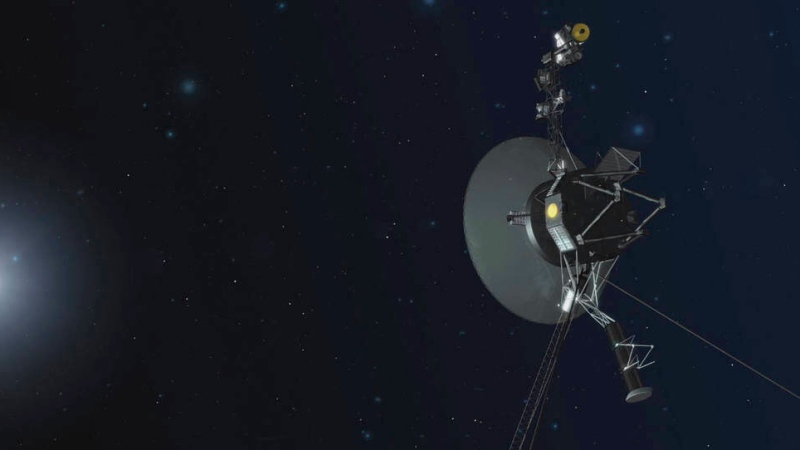

The last spacecraft to fly over the sun's poles was another joint ESA and NASA venture, the Ulysses mission, which launched in 1990 and was decommissioned in 2009. But according to NASA, Ulysses never got any closer to the sun than the Earth does, and didn’t have any cameras onboard.

Solar Orbiter will also work with another probe studying the sun -- Parker Solar Probe, which was launched in 2018 and has completed four close solar passes on the ecliptic plane.

Delaney said that, on a scale of one to ten, he is “eight plus” excited about this mission.

“We don’t get these probes coming around very often,” he said. “Knowing how the sun is operating and protecting ourselves in the event that something is going to happen – that’s rather important to modern civilization.”

Correction:

An earlier version of the article incorrectly identified the distance from the sun to the Earth as 147 million miles.This has been changed to kilometres.