TORONTO -

The skeletal remains of a man wearing ankle shackles discovered during construction work in Rutland, U.K, is proof that slavery was a part of life in Britain while it was under Roman rule, a new study suggests.

The study, entitled “An Unusual Roman Fettered Burial from Great Casteron, Rutland,” published Monday by Cambridge University press in the journal Brittania, documents the 2015 discovery of a male adult skeleton secured at the ankles with a pair of iron fetters, closed by a padlock, buried in a ditch.

Radiocarbon dating suggests the remains date back to between AD226 to AD427.

“The chance discovery of a burial of an enslaved person at Great Casterton, reminds us that even though the remains of enslaved people can often be difficult to identify, that they existed during the Roman period in Britain is unquestionable,” archeologist Chris Chinnock said in a Museum of London Archaeology (MOLA) press release. “Therefore, the questions we attempt to address from the archaeological remains can, and should, recognise the role slavery has played throughout history.”

Chinnock states in a blog post that “it may seem obvious to state that slavery existed within the Roman Empire,” but he notes that little physical evidence such as artifacts “directly related to the practice of slavery” are not commonly found, and historians and archeologists have had to rely on inscriptions.

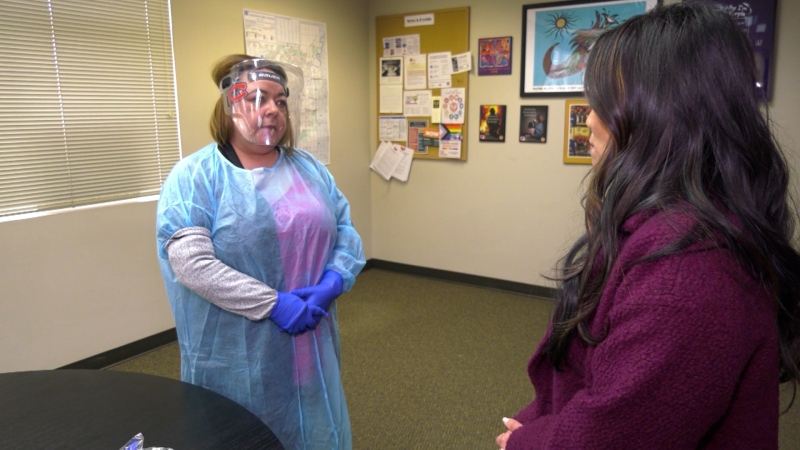

The skeleton, found in the village of Great Casterton, was lying slightly on his right side, with his left side and arm elevated on a slope.

His feet, wearing the shackles, faced south, and examination of his bones showed that he had a physically demanding life and evidence of injuries, the study says.

The skull and neck vertebrae were missing, with researchers musing that it could have been removed prior to burial – but more likely had been destroyed during other modern construction work in the area. The cause of death is unknown.

A Roman cemetery is located 60 metres away from the skeleton, leading researchers to believe a the man had been thrown in the ditch and then covered over.

The iron fetters are clearly seen in this image of the skeletal remains uncovered at Great Casterton. (MOLA)

The iron fetters are clearly seen in this image of the skeletal remains uncovered at Great Casterton. (MOLA)

The iron fetters are clearly seen in this image of the skeletal remains uncovered at Great Casterton. (MOLA)

Researchers also posited that the shackles, which normally were seen as valuable objects to reuse on enslaved peoples in the event of a death, could have been added after the man was dead as an insult or to brand him as a criminal.

“For living wearers, shackles were both a form of imprisonment and a method of punishment, a source of discomfort, pain and stigma which may have left scars even after they had been removed,” said MOLA archeologist Michael Marshall in the release. “However, the discovery of shackles in a burial suggests that they may have been used to exert power over dead bodies as well as the living, hinting that some of the symbolic consequences of imprisonment and slavery could extend even beyond death.”

The study says the identity of the man may never be known, but that the skeleton at Great Casterton proves a need for more data to further examine the practice and history of slavery in Roman Britain.