TORONTO -- To bee or not to bee? Researchers have synthesized a particle as small as pollen, which, when fed to bees, may be able to help them to detoxify hives damaged by pesticides in order to protect the insects.

"This is a low-cost, scalable solution which we hope will be a first step to address the insecticide toxicity issue and contribute to the protection of managed pollinators," Minglin Ma, an associate professor at Cornell University and senior author of the research, said in a press release.

The research was published earlier this month in the scientific journal Nature Food.

The wax and pollen in around 98 per cent of commercial bee hives in the U.S. have been contaminated by various pesticides, according to the release, and pesticides cause beekeepers to lose around a third of their hives annually.

The toxins in pesticides lower a bee’s immunity to mites and disease, which is concerning considering how important a role bees play in the human food chain. Bees help to fertilize crops, which “lead to production of a third of the food we consume,” the release said.

In Canada, there are around 10,000 commercial beekeepers, and the value of these honey bees to pollination is estimated at more than $2 billion annually, according to the Canadian Honey Council.

"We have a solution whereby beekeepers can feed their bees our microparticle products in pollen patties or in a sugar syrup, and it allows them to detoxify the hive of any pesticides that they might find," James Webb said in the release. Webb is a co-author of the paper and CEO of Beemmunity, a new company hoping to use this technology to assist commercial beekeepers.

The new microparticles are formulated to battle specific pesticides known as organophosphate-based insecticides, which make up a third of the market, according to the release.

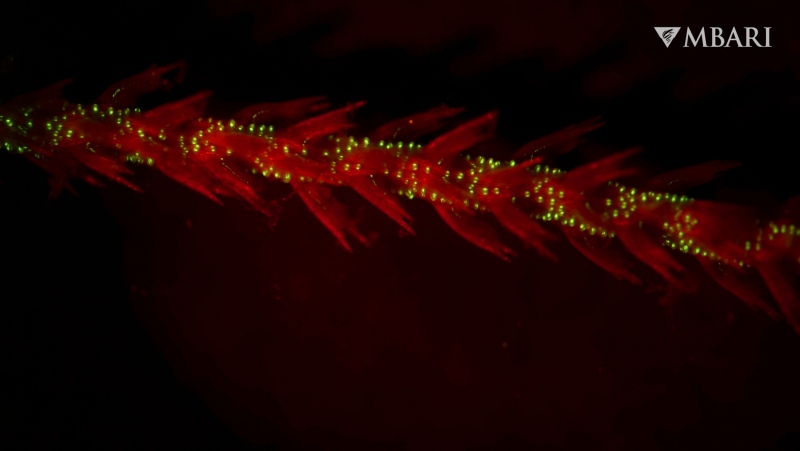

How it works is that these microparticles, called pollen-inspired microparticles or PIMs, contain specific enzymes that can help detoxify hives.

Since the bees consume the microparticles, researchers had to ensure that the microparticles could survive the pH of the bees’ gut. Each PIM has a protective casing so that it can pass through the acidic portion of the bees.

Researchers tested the microparticles by having live bees ingest them and then feed on pollen patties contaminated with a common pesticide called malathion.

A control group of other bees were only given the pesticide-laced pollen patties with no PIMs to protect them.

While the bees in the control group died within a matter of days, 100 per cent of those who received the PIMs survived, the release said.

Beemunity is looking to take this technology and create more microparticles that can break down pesticides.

The idea is that commercial beekeepers could integrate these microparticles into “supplemental feeds such as pollen patties or dietary syrup,” the abstract of the research states.

Larger trials are to be run this summer on 240 hives in New Jersey, according to the release, and Beemunity plans to officially launch products around February 2022.