Northern communities eroding away into the ocean. Polar bears flooding south into more Canadian cities. Trade upheaval as the potential for new ship routes opens up where thick ice used to block the way.

These are some of the things we would be facing if the ice in the Arctic Ocean vanished completely every summer.

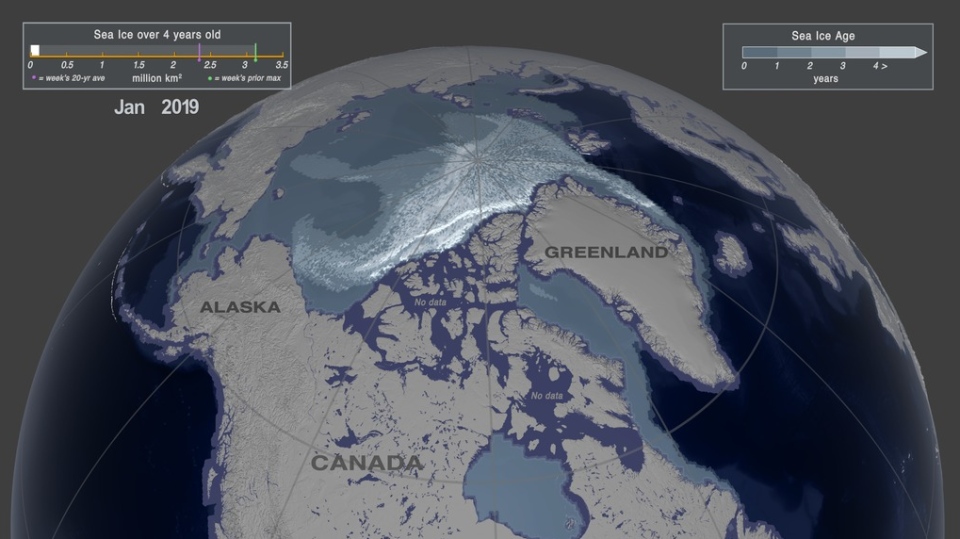

NASA has released a visualization of sea ice in the Arctic that shows a dramatic loss of perennial ice in the Arctic Circle within the last 35 years.

If it continues -- and Mark Serreze, Director of the National Snow & Ice Data Center, says it’s almost certain that it has gone on too long to reverse the effects -- we may be learning to navigate a drastically changed world by the 2050s.

“Probably a few decades from now, you'll go out and look at the Arctic and there won't be any sea ice there at all,” Serreze told CTVNews.ca in a phone interview. “(This data) means that we are headed to a seasonally ice-free Arctic Ocean.”

New sheets of sea ice spread and melt with the seasons, but the Arctic Circle has always been covered with a percentage of older ice, or perennial ice, which survives seasonal changes. This is why in the dead of summer there is still ice at the top of the world.

According to the new data, accumulated by the NSIDC and visualized by NASA, in the first week of January in 1984, the area in the Arctic Ocean covered by sea ice older than four years was over 3.1 million square kilometres.

By contrast, in the first week of January in 2019, NASA found that the area covered by the older sea ice had plunged down to only 116,000 square kilometres.

This means that perennial ice in the Arctic Circle has shrunk by more than 95 per cent in only 35 years.

Serreze said that if someone were to stand today at Point Barrow -- the northern-most point of the U.S., in Alaska -- and look out to the north, they would “find no sea ice for probably 450 miles.

“Normally you should find it still fairly close to the shore at this time of the year,” he said. “That's kind of an example of these huge changes we're seeing.”

The ramifications of this could be massive, Serreze said, from environmental effects to cultural ones, threatening the safety and livelihoods of entire communities.

“The people who live (in northern communities) are being affected because their Indigenous hunting practices are being affected,” Serreze said. “They can't get out onto the ice. Same with the polar bears and the walrus can't get out on the ice.”

He added that coastal erosion is becoming more and more of a problem in parts of the Arctic, explaining that some “coastal areas are basically sediments that are glued together by permafrost.” Not only is the permafrost being affected by global temperatures increasing in the air and the water, but the loss of sea ice cover is exposing these areas to harsher waves and physical punishment from the ocean.

“You're seeing areas along the coast of Alaska that are receding 15 to 25 feet a year,” Serreze said. “Because of the loss of the sea ice cover.”

The continued loss of sea ice will have effects on everything “from plankton all the way through the top predators,” according to Serreze.

“The take home message is that climate change is real,” he said. “It is not something that is out there 30 years from now, 50 years from now that our children or grandchildren are going to have to deal with -- it is here and it is now.”

Deniers of climate change often point to seasonal variations in phenomenon such as mass ice melting and global temperatures as a sign that the world is not undergoing a human-created crisis, but is merely balancing itself out naturally.

This is not the case, according to the data.

Serreze said that when they looked at the levels of perennial sea ice, they did not find a smooth decline, but instead many ups and downs. This is due, he acknowledges, to the “natural variability in climate.”

However, this natural variability is “all superimposed upon those overall trends towards less ice and thinner ice.”

The dramatic overall change is most clear in NASA’s visualization.

The visualization shows the top of a spinning Earth, and as the weeks track by year after year, the Arctic ice shrinks and grows with the seasons.

The colour of the ice in the visualization indicates the age of the ice -- brand new ice that spreads across the top of the globe into Russia and Canada every winter and then melts in the spring is a darker blue, while ice in the Arctic Circle that is older than four years is coloured in white. Shades of pale blue in between the two extremes indicate ice of one, two or three years of age.

The seasonal variation is fairly consistent, but as the years go by, the visualization shows the patches of older white ice growing smaller and smaller, until it is barely a pale streak in the blue.

It’s not just the diminishing amount of square kilometres covered that is a problem, but the quality of the ice itself. The ice cover is thinning now, and Serreze said that all the old ice is almost entirely gone.

“If you were to go out into the Arctic Ocean, say 40 years ago, you might find ice that had been drifting around the Arctic Ocean for 10 years or more,” he said.

Not anymore.

As the landscape changes, so would the meaning of the Arctic itself, Serreze said.

“The Arctic is becoming very important strategically and economically because as the Arctic loses its ice cover, we're going to be opening the region to shipping,” Serreze said, “to extraction of oil and gas reserves that we couldn't get to before because of the ice. So as we lose that ice cover, this is going to have some big effects.”

When exactly we could see an ice-free summer Arctic depends in part on our actions right now, Serezze said.

We could slow it, or put it off completely, “but if you look at what the different projections are based on (the) greenhouse gas emissions rate we're seeing these days, we keep coming up with somewhere in the 2050s.

“But some projections are from much earlier than that,” he said. “I've been on record saying as early as 2030, we might see (a seasonally ice-free Arctic).”

The NSIDC has been studying the Arctic and other frozen realms for decades, piecing together a growing picture of the uncertain future humanity is building.

NASA’s visualization, with the alarming shrink of ice so clearly laid out on our planet, may come as a shock to some. But Serreze is not surprised by this data.

“We have always known that as climate change takes hold, it's the Arctic that would be leading the way. It's the Arctic where you'd see the changes first and where they'd be the most pronounced,” he said.

“And here we are. It's exactly what we see. And it's sort of a case where we hate to say, we told you so, but we told you so.”