TORONTO -- New sets of Neanderthal remains found in the historical archeological site known as the “Shanidar Cave” in the foothills of Iraqi Kurdistan could unlock secrets of ancient burial rites, according to a new study in the Antiquity journal.

Shanidar Cave is one of the most important sites in mid-20th century archeology – deemed so after it was first excavated in the 1950s by archeologist Ralph Solecki who uncovered partial remains of 10 Neanderthal men, women and children.

His findings “were really central to the debate about Neanderthal behaviour and cognition, and what their mental capacities were,” said lead study author Dr. Emma Pomeroy of the University of Cambridge in a telephone interview with CTVNews.ca Monday.

One set of remains, known as the “flower burial” or “Shanidar 4,” had clusters of ancient pollen surrounding the skeleton, which Solecki argued was evidence that Neanderthals buried their dead and conducted funeral rites involving flowers.

Another skeleton, known as “Shanidar 1,” had evidence of extensive injuries, including a withered and partially amputated arm, evidence of blindness in one eye, deafness, and an infection in the bones. Yet that person lived to “quite an old age,” said Pomeroy.

This was interpreted as potential evidence that Neanderthals had the capacity for compassion and taking care of injured members of their group.

Solecki’s findings prompted re-evaluation of previously held views of Neanderthals as animalistic and unintelligent, and sparked fierce debate over whether Neanderthals had any -- or were capable of -- cultural sophistication.

A dig scheduled to continue Solecki’s work in 2014 was abandoned early due to an ISIS threat to nearby Erbil, according to Pomeroy, but from 2015 onwards annual digs at Shanidar Cave have continued.

A map of the location of Shanidar Cave in Iraqi Kurdistan (Antiquity)

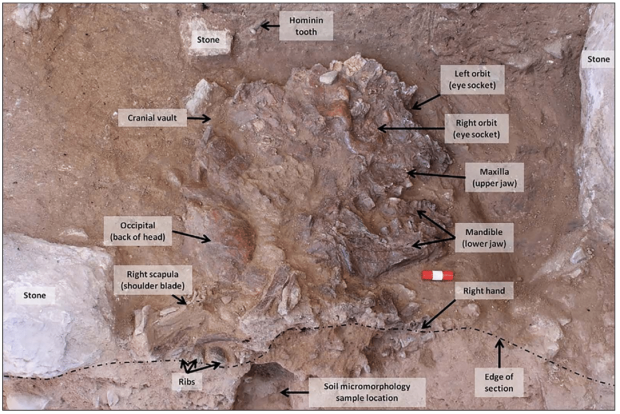

The 2018-2019 dig, which reopened Solecki’s original trench from the ‘50s discussed in February’s edition of the Antiquity journal, marks the first articulated Neanderthal skeleton to be excavated in more than 20 years.

“What’s really exciting from this is we have these articulated Neanderthal remains…that appear to be in the position in which were left,” Pomeroy said. “What’s important here is that we were able to excavate it with all the modern techniques and modern archeological science that will actually give us better insight into what actually happened to these bodies.”

Researchers from Cambridge, Birbeck and Liverpool John Moores Universities in the U.K., in conjunction with the Kurdistan General Directorate of Antiquities, were able to collect new sediment samples and uncovered the crushed skull and torso bones of a new Shanidar Neanderthal specimen.

Early evidence suggests the new set of remains – dubbed “Shanidar Z” by archeologists – is approximately 70,000 years-old.

Pomeroy said that by using soil micromorphology – the practice of extracting small blocks of soil, embedding them with resin and then slicing them very thinly to be studied under a microscope – researchers found evidence of “the depression in which the skeleton lies was intentionally dug.”

The crushed skull remains and other skeletal fragments of "Shanidar Z" in situ. (Graeme Barker/Antiquity)

After excavating Shanidar Z and cleaning, stabilizing and constructing the “very fragile bones,” the skeleton was moved to the U.K. and is currently on loan while being examined further at Cambridge University.

The study raises important questions over whether or not Neanderthals in the area returned to Shanidar Cave to inter their dead, which would denote cultural complexity, the study says.

Scans of the wedge-like petrous bone in the base of the skull of Shanidar Z appear to be intact, giving researchers hope of extracting ancient DNA to determine myriad of clues about Neanderthals and the “interbreeding” with modern humans thought to have occurred in that region.

“We don’t have any Neanderthal DNA from this region, it’s all from much further north so it will help us understand the genetic variability of Neanderthals,” said Pomeroy.

“One theory is that loss of genetic variability over time is one of the reasons why Neanderthals eventually went extinct,” she continued.

However, Pomeroy emphasized that research and archaeological excavation would be an ongoing process.

“We still have a lot of work to do,” she said.