PARIS -- Sustained greenhouse gas emissions could see global sea levels rise nearly 40 centimetres this century as ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland continue to melt, a major international study concluded Thursday.

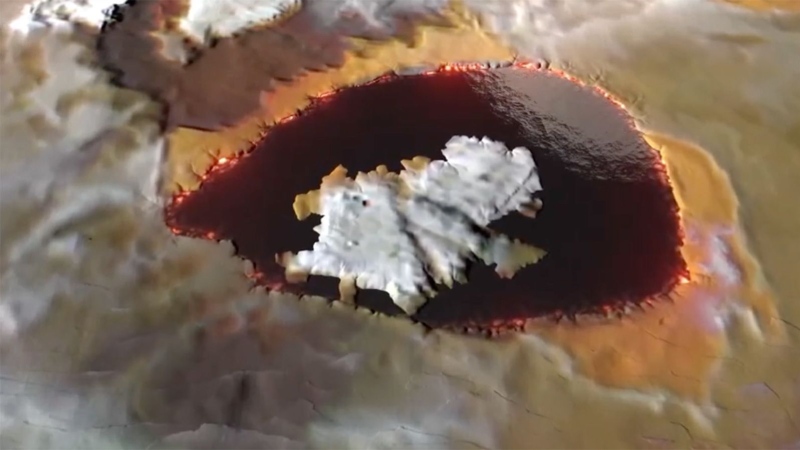

The gigantic ice caps contain enough frozen water to lift oceans 65 metres, and researchers are increasingly concerned that their melt rates are tracking the UN's worst case scenarios for sea level rise.

Experts from more than three dozen research institutions used temperature and ocean salinity data to conduct multiple computer models simulating the potential ice loss in Greenland and Antarctic glaciers.

They tracked two climate scenarios -- one where mankind continues to pollute at current levels and another where carbon emissions are drastically reduced by 2100.

They found that under the high emissions scenario ice loss in Antarctica would see sea levels rise 30 cm by century's end, with Greenland contributing an additional 9 cm.

Such an increase would have a devastating impact worldwide, increasing the destructive power of storm surges and exposing coastal regions home to hundreds of millions of people to repeated and severe flooding.

Even in the lower emissions scenario, the Greenland sheet would raise oceans by around 3 cm by 2100 -- beyond what is already destined to melt due to the additional 1 C of warming humans have caused in the industrial age.

"It's not so surprising that if we warm the planet more, more ice will be lost," said Anders Levermann, an expert on climate and ice sheets at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research.

"If we emit more carbon into the atmosphere we will have more ice loss in Greenland and Antarctic," he told AFP.

"We have in our hands how fast we let sea levels rise and how much we let sea levels rise eventually."

OUTPACING PREDICTIONS

Until the turn of the 21st century, the West Antarctic and Greenland ice sheets generally accumulated as much mass as they shed. Runoff, in other words, was compensated by fresh snowfall.

But over the last two decades, the gathering pace of global warming has upended this balance.

Last year, Greenland lost a record 532 billion tonnes of ice -- the equivalent of six Olympic pools of cold, fresh water flowing into the Atlantic every second. This run-off accounted for 40 percent of sea level rise in 2019.

The UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in a special report on Earth's frozen spaces predicted last year that Greenland ice melt could contribute 8-27 cm to ocean levels by 2100.

It estimated Antarctica could add 3-28 cm on top of that.

A study published earlier this month in Nature Climate Change said the mass already lost by melt-water and crumbling ice between 2007-2017 aligned with the most extreme IPCC forecasts for the two sheets.

They also predicted a maximum of 40 cm sea level rise by 2100.

Authors of Thursday's research, published in a special edition of The Cryosphere Journal, said it highlighted the role emissions will play this century on the world's seas.

Levermann said that the wide variation in predicted levels of ice melt was no reason not to reduce emissions as quickly as possible.

"Uncertainty cannot be a reason to wait-and-see here -– it is in fact a reason for urgent action," he said.

"We already know that something will happen. We just don't know how bad it is going to get."