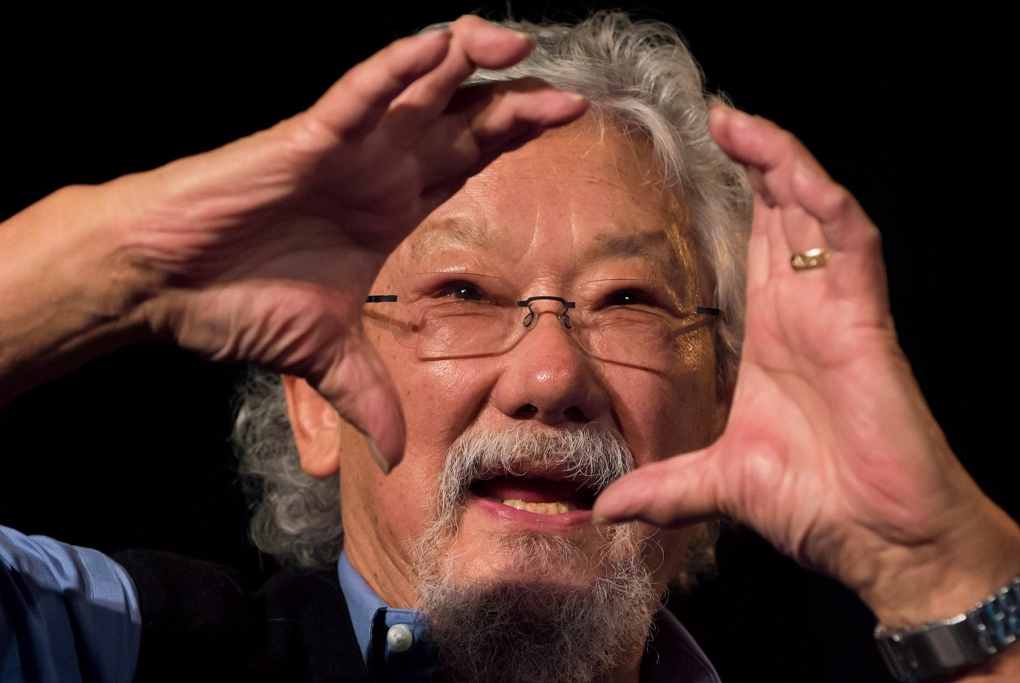

TORONTO -- David Suzuki can't help but wonder if he's harbouring a ticking time bomb in his brain.

It's no idle notion -- the scientist-broadcaster's mother and three of her siblings died of Alzheimer's -- and as a geneticist, Suzuki knows the progressive neurodegenerative disease can turn up from one generation to the next.

Given his family history and his public profile, Suzuki was approached by a pair of documentary makers, who wanted to make a film about Alzheimer's and global research efforts to discover the cause of the disease and potential treatments.

The result is "Untangling Alzheimer's," a one-hour documentary to air Thursday on CBC's "The Nature of Things," the long-running show that's been hosted by the well-known environmentalist for the last 30 years. (Check local listings).

"I was a bit nervous about it because I thought: 'Well, does my personal story distract from the science of it?"' Suzuki admitted during a recent interview in Toronto. "I wanted it to be just a straight science story."

"Untangling Alzheimer's" writer-director Roberto Verdecchia said Suzuki's willingness to expose himself and his family's background makes for a compelling story.

"With this show, audiences will look at the disease in a very intimate way," both from the perspectives of "those suffering from it and for those close to it," Verdecchia said.

Weaving several threads about cutting-edge research through the fabric of his family's experience with dementia, Suzuki gives viewers insight into the devastating disease that affects more than 35 million people worldwide, a number expected to double every 20 years.

"My mother started to show signs of dementia when she was in her late 60s, early 70s," he said. "I didn't think she had Alzheimer's -- her temperament never changed. She was always just this even-tempered person. And I wasn't really aware of the extent to which she was really depressed about her condition."

Alzheimer's and other dementias relentlessly diminish a person's cognitive abilities, such as memory, and can severely alter mood and personality. Eventually, the disease leads to a breakdown in physical function that ends in death.

"Of course, when your mother develops a condition, you begin to think ... is there a genetic component?" said the scientist.

There is a relatively rare form of early-onset dementia caused by a single dominant gene, and if one parent carries that gene, offspring have a 50 per cent chance of developing the disease, which shows up in the 30s or 40s.

That wasn't the case with his mother. But even so, Suzuki knows he has about a 20 to 25 per cent increased risk of developing Alzheimer's because of his family history.

"I guess I've been kind of philosophical about it. We're all going to die of something. She died at 74 and I'm 77, so it's something that I'm aware of, but it doesn't hang over my head.

"What the chances will be for my children, I don't know at this point," said the father of five from two marriages. "But they're going to have to live with it and face it. It may be that by the time my children are in the zone for that kind of dementia to kick in that there will be some kind of drugs."

Yet, he points out, medical science is still at a "very early stage" in its attempts to demystify Alzheimer's.

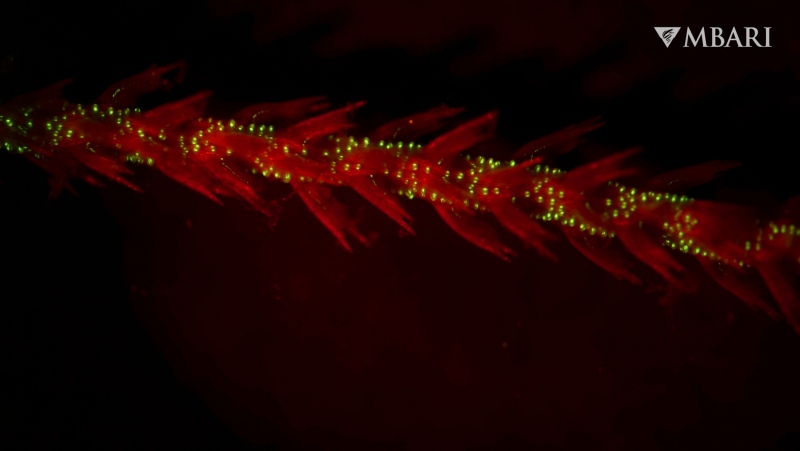

Its exact cause is unknown. But bit by bit, more is being learned about the hallmarks present in the brains of dementia patients, among them twisting amyloid plaques that strangle neurons and their connections, causing swaths of brain tissue to wither and die.

There is no cure, and those drugs available are stop-gaps that halt progression, at best. Even an unequivocal diagnosis of Alzheimer's isn't possible until a person has died and their autopsied brain is examined for signs of the disease.

Still, researchers are casting a wide net in efforts to understand its cause, how to prevent it, the means to detect it earlier, and ultimately how to treat it.

One direction Suzuki finds most intriguing is that taken by Boston University researcher Lee Goldstein, who is investigating whether amyloid plaques that can be detected in the eyes might be a predictive test for the development of Alzheimer's.

"We have to wait now to look at those structures and follow people over time," he said. "But if that becomes a tool for prediction, that those people with a certain level of amyloid plaques in the eye are the ones that get dementia, then I think we've got a very good handle at studying the disease itself.

"Otherwise, we're left with having to wait until people die and then look at the brain and find out."

Suzuki, who travelled to Boston to interview Goldstein, had his own eyes tested for amyloid, but didn't want to know the results.

"If by analyzing it and saying: 'Oh, you're going to get it,' there was a way of treating it, then of course I'd want to know. But right now there's nothing you can do about it. So why would I want to know and have it hanging over my head?

"Right now, I'm feeling fine. My mind is still ticking. My body's still ticking and I think the best thing I can do for a variety of reasons is to get to the gym as often as I can and exercise."

Indeed, research has shown that both physical and mental exercise can at least stave off symptoms of dementia, though they may be unlikely to prevent the neurodegenerative disease entirely.

Two U.S. researchers profiled in the program are looking at the role of inadequate insulin as a possible cause of dementia, and one of them is testing an experimental insulin spray to determine if delivering the hormone into nasal cavities might prevent and/or treat the condition.

The documentary also looks at the work of Dr. Andres Lozano, a Toronto neurosurgeon who is testing deep-brain stimulation, or DBS -- in which electrodes placed in key areas of the brain are activated much like a pacemaker -- as a potential treatment.

While it's an interesting concept that seems to have helped a few patients, at least in the short term, Suzuki confides that DBS may be too blunt an instrument at this point in its development. And even if it were refined and proved effective, it would likely be impractical as a widely used treatment due to cost and the surgical resources required.

However, with the first wave of baby boomers hitting age 65, clearly the clock is ticking.

The Alzheimer's Society estimates that almost 750,000 Canadians have some form of cognitive impairment, including dementia. With the risk of dementia doubling every five years after age 65, that figure is predicted to rise to 1.4 million by 2031 if no treatment or preventive strategy is found.

"The important thing now is that we know this wave of Alzheimer's is coming because of the aging population," warned Suzuki. "So we've really got to be thinking about what are we going to do to deal with that. We can't let it overwhelm our medical services. I don't think we're going to have the ability to house them all in facilities.

"Too often we are a reactive creature. We let the crisis happen and then say, 'Oh my God, what are we going to do?' But with dementia, we know it's coming. We know we don't have any treatments right now. So we better start looking at how we're going to handle this."