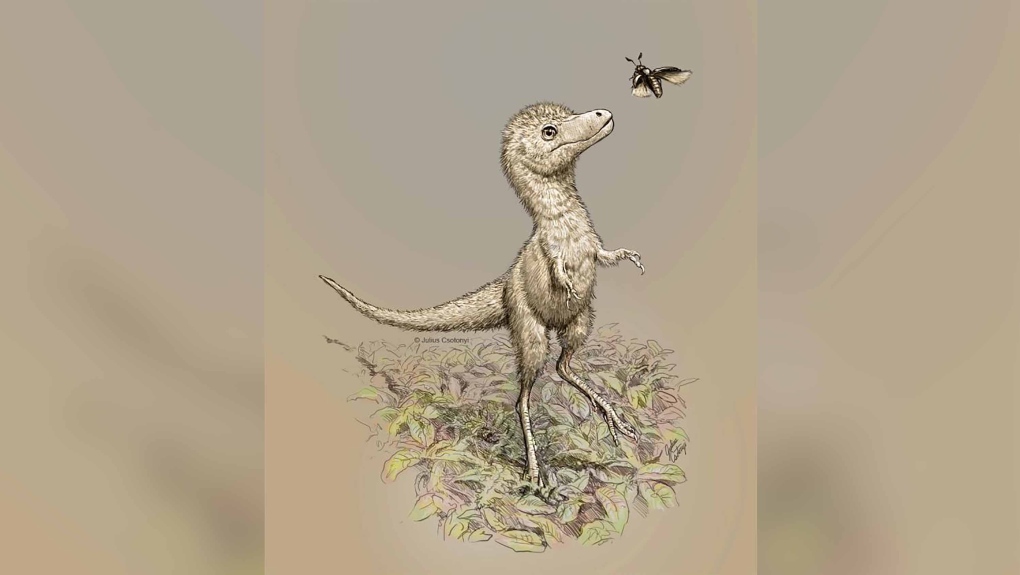

Tyrannosaurs were fearsome predators in the dinosaur kingdom, but new research shows their hatchlings were about as big as a medium-sized dog.

Researchers studying the first-known fossils of tyrannosaur embryos suggest the dinosaurs were approximately three feet long when they hatched, according to a study from the University of Edinburgh, published Monday.

A team of paleontologists studied the fossilized remains of a tyrannosaurus embryo, namely a jaw bone and claw that were found in Canada and the US, respectively.

After producing 3D scans of the remains, researchers were able to predict that the dinosaurs would have hatched from eggs about 17 inches long.

Remains of tyrannosaurus eggs have never been found, but this finding could help paleontologists spot them in the future.

"Dinosaur babies are very rare," lead study author Greg Funston, a paleontologist at the University Edinburgh, told CNN, explaining that larger specimens are better represented in the fossil record because their bones were more durable.

"Most dinosaurs didn't nest in an area where their eggs could be easily buried," Funston added, making the preservation of this kind of find even rarer. "It's quite a big deal," he said.

The claw is from an Albertosaurus and the jaw bone from a Daspletosaurus, both of which would have grown to around 35 feet in length.

They were slightly smaller than their more famous cousin, Tyrannosaurus rex, which grew up to 40 feet in length, Funston said.

Researchers found the jaw bone, which is just over an inch long, had features distinctive to the tyrannosaur group, including a pronounced chin.

While tyrannosaurs are known to have undergone many changes over their lifetime, this shows the embryos already had certain physical traits before they hatched, Funston said.

The discovery could help settle debates over whether other specimens in the fossil record come from new species or younger specimens of known species, he added.

Tyrannosaurs lived more than 70 million years ago. Little is known about their early development as most specimens that have been studied are from older animals, Funston said, but researchers now know they were born with a full set of teeth and could hunt for themselves, albeit on smaller prey than adults.

"These were animals that were hatching and were probably fairly active relatively soon after they hatched," Funston said.

The study was published in the Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences.

Funston said he plans to try to produce scans of the remains at a higher resolution, to enable the study of tooth development, which could reveal how long the tyrannosaurs spent inside the eggs before hatching.