About 74,000 years ago, Sumatra's Mount Toba experienced a super-eruption -- an event scientists suspect was large enough to wipe out a majority of early humans living at the time, slowing down the spread of humanity.

But researchers have discovered evidence that Homo sapiens were migrating before, during and after the event, according to a new study.

The explosive event, which was estimated to be 5,000 times the size of the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption, is thought to have created a volcanic winter that impacted the spread of ancient humans.

While there's no hard evidence, the volcanic winter is estimated to have lasted between six and ten years, followed by a reduction in global temperatures for about a thousand years beyond that. If true, this would have devastated humans, human ancestors and animal populations across Asia.

But new research shows that the situation may not have been that dire.

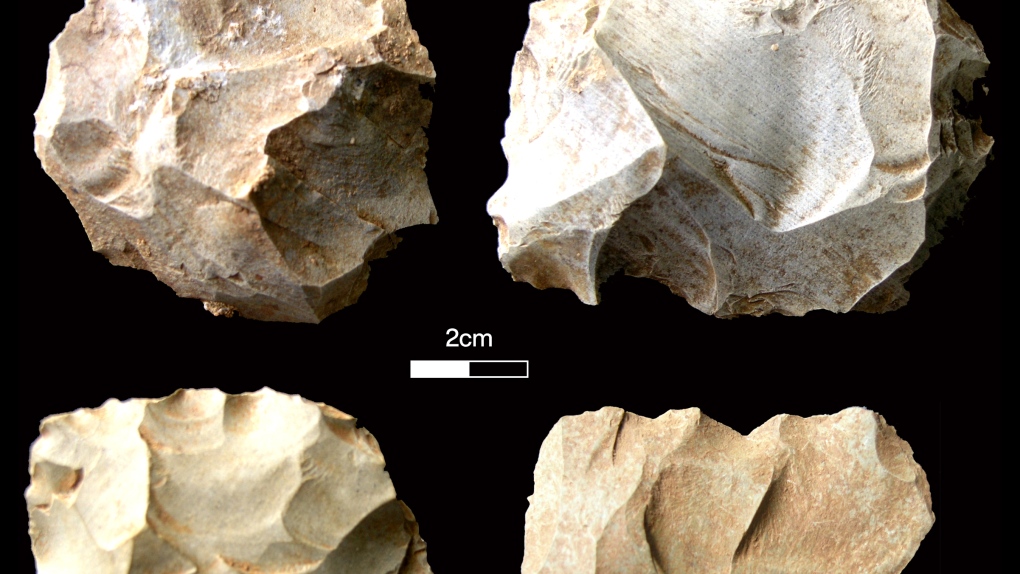

Researchers investigating a site called Dhaba in Central India's Middle Son River Valley uncovered evidence revealing that humans have occupied the site continuously for the last 80,000 years. Stone tools found at the site are also similar to those associated with Middle Stone Age humans in Africa and even Australia, suggesting that they were all forged by migrating Homo sapiens.

The discovery of the tools also suggests that Homo sapiens were living in Asia earlier than expected. The study published Tuesday in the journal Nature Communications.

"Populations at Dhaba were using stone tools that were similar to the toolkits being used by Homo sapiens in Africa at the same time," said Chris Clarkson, lead study author at the University of Queensland.

"The fact that these toolkits did not disappear at the time of the Toba super-eruption or change dramatically soon after indicates that human populations survived the so-called catastrophe and continued to create tools to modify their environments."

The discovery of the tools showcases the tenacity of hunter-gatherer communities who adapted despite changes in their environment after one of the largest volcanic events to occur during the last two million years.

However, this was not a lasting legacy. For example, the humans who survived this event didn't thrive enough to the point that they contributed to the current gene pool.

They likely suffered due to other challenges and the glacial period that followed the eruption.

"The archeological record demonstrates that although humans sometimes show a remarkable level of resilience to challenges, it is also clear that people did not necessarily always prosper over the long term," said Michael Petraglia, study co-author at the Max Planck Institute for the Science of Human History.

The findings have a larger implication for the arrival of humans in India because so far no human remains from this time period have been recovered in the area.

Recent studies suggest that modern humans migrated from Africa between 52,000 to 70,000 years ago. Fossil and stone tool evidence is beginning to show where they ended up and when, including a human presence in China before 80,000 years ago, Southeast Asia between 63,000 and 73,000 years ago, as well as Australia by 65,000 years ago. Australia marks the end of the "southern arc" of the migration dispersal, meaning that Homo sapiens were in South Asia beforehand, according to the study.

"The Dhaba locality serves as an important bridge linking regions with similar archeology to the east and west," the authors wrote in the study.