Somewhere under the forests, soil and bedrock of southern Quebec lie the ancient, undiscovered traces of an enormous meteor strike so catastrophic that it helped change the Earth's climate and alter human history.

At least, that's what Dartmouth University geochemist Mukul Sharma argues in a newly published paper, which could lead to an explanation of one of the most baffling episodes in our planet's history.

"The whole idea is controversial," he said. "There's a correlation between a climate event and a meteor, but what is the cause? How did it all play out?"

Sharma has long been fascinated by a period about 13,000 years ago called the Younger Dryas, during which the Earth suddenly reversed a warming trend and cooled radically for more than a millennium.

North American ice-age mammals from camels to ground sloths to sabre-tooth tigers became extinct. Ancient humans had to put away their mastodon spears and learn to survive on roots, berries and small game -- and maybe even shift to agriculture.

"It was an abrupt event when the Earth (was starting) to warm up," said Sharma. "Suddenly, the climate changes again to very, very cold conditions and remains so for 1,400 years and then goes back merrily to warming again."

But why?

Some scientists hypothesize that it was related to the collapse of a giant ice dam formed by receding glaciers, which released a huge flood of cold freshwater that disrupted ocean currents and reversed climate trends. Others suggest something else must have been at work as well -- perhaps a series of major meteor strikes.

Remains that could be from meteors dating from the onset of the Dryas have been found. But -- perhaps because most of North America was covered by ice at the time -- no evidence of an actual impact has been discovered.

Enter Sharma.

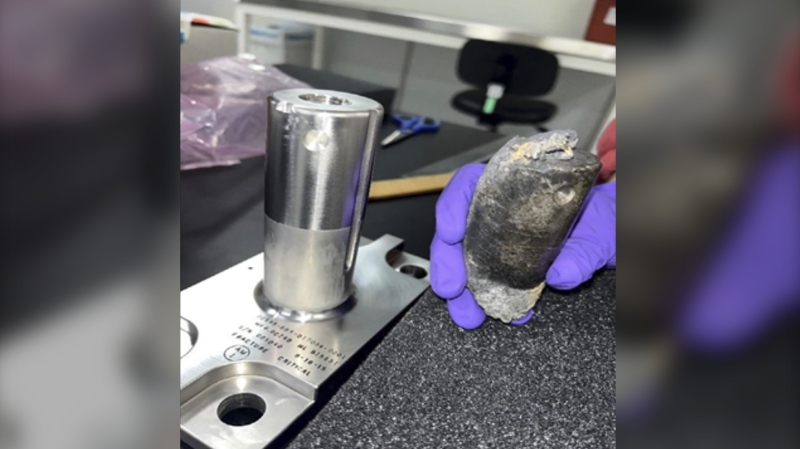

He and his colleagues began examining tiny, marble-like rocks found in Pennsylvania and New Jersey that date right from the start of the Dryas period. These "spherules" contained minerals that could only have been produced through extraordinary heat.

"The only place where you can make these on the surface of the Earth is in a blast furnace," Sharma said. "And not everywhere in a blast furnace -- in the hottest part.

"Clearly, these objects were produced in an impact fireball."

What's more, Sharma found the spherules weren't local. The combination of isotopes they held closely matched those from areas in southern Quebec along the Gulf of St. Lawrence.

What he'd discovered was evidence of a meteor strike so powerful it could punch through more than a kilometre of ice and still retain enough energy to generate temperatures upwards of 1,700 C, send a huge mushroom cloud into the sky and hurl rubble over a good chunk of the continent.

That, perhaps in conjunction with other strikes around the same time, could have been disruptive enough to contribute to the climatic hiccup of the Younger Dryas.

Never mind that the actual crater hasn't been found. It may lie buried under thick beds of glacial till left behind as the ice finally retreated, Sharma suggested.

Craters in the area are still being discovered, including one as recently as 2001 in Sept-Iles that has been dated to the start of the Younger Dryas.

"Is it possible that there is a structure that has been buried and has not been found?" asked Sharma. "All those things are possible."

He acknowledges that his discovery doesn't prove meteors caused the Earth's sudden cooling. It does, however, suggest there was at least one major event affecting the atmosphere that occurred right around the same time.

"(The Younger Dryas) is an interesting event.

"Some would say it's a freakish event. So if it's a freak event, it could be related to some kind of meteorite, which does not happen every day."