Serial killer Robert Pickton got away with murdering women for years because of a systemic police bias against his poor, aboriginal, drug-addicted victims, a public inquiry has concluded.

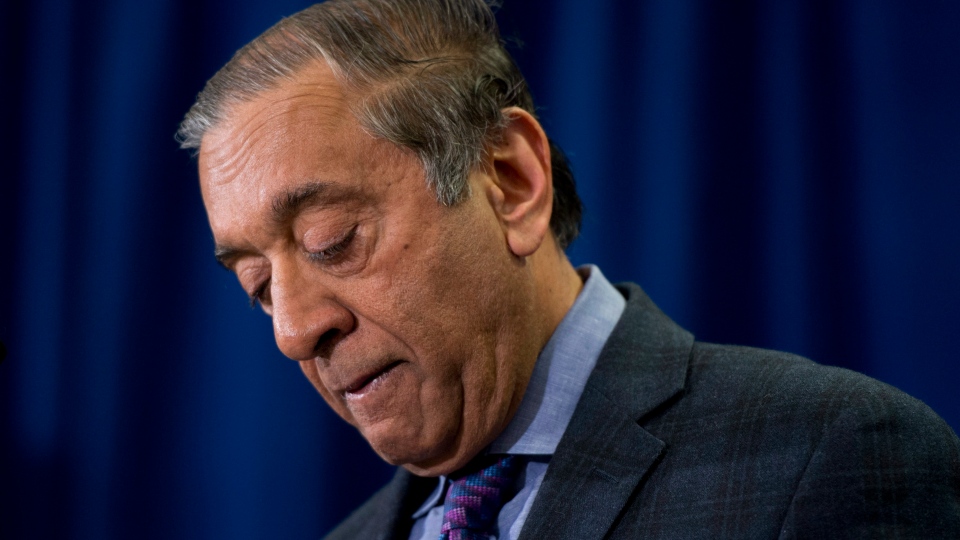

Commissioner Wally Oppal released Monday a scathing, 1,448-page report that examined the authorities’ handling of dozens of cases of murdered and missing aboriginal women, many of them from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Oppal had spent eight months hearing evidence about Pickton’s victims and how their disappearances were treated by the Vancouver police and the Port Coquitlam RCMP.

He concluded that “a systemic bias by the police” failed to apprehend Pickton before he killed scores of women, even though there was evidence from as early as 1991 to indicate that a serial killer may be on the loose.

Pickton was convicted of killing six sex workers and sentenced to life in prison. Many more murder cases were linked to his farm, but ultimately not pursued in court.

“The women were poor, they were addicted, vulnerable, aboriginal,” Oppal told a news conference Monday afternoon. “As a group they were dismissed.”

However, Oppal blamed the bias on the entire system, not individual police officers who investigated the women’s disappearances. He singled out several cops who he said did their jobs “diligently,” even when they had no support from their supervisors.

Oppal said a series of “blatant failures” and “public indifference” left Pickton free to lure so many aboriginal sex trade workers to his farm and kill them.

Among the police’s missteps was a failure to take the complaints of victims’ families seriously, poor report-taking, poor follow-up and a failure to work together with other police agencies, Oppal said.

He said that the missing and murdered women were mothers, daughters, sisters and friends, but the society treated them like “nobodies” because they were so marginalized.

“Imagine what it’s like to be alone, afraid, forsaken,” Oppal said. “Think how it would feel if you were dismissed.”

He said the term “missing” is a misnomer because the women “didn’t just go away.”

“They were taken. We know they were murdered.”

Oppal called the murders and disappearances a “tragedy of epic proportions,” which could have been avoided if police took the reports of missing women seriously from the start.

Had a slew of women gone missing from the affluent west side of Vancouver, the police response would have been much different, Oppal said.

As he spoke, a group of aboriginal women who attended the news conference began singing and drumming. Later, some of them shouted the words “systemic racism” and “racial profiling,” as Oppal talked about the problems plaguing aboriginal communities.

Many relatives of the missing and murdered women have been very critical of the inquiry, saying it ignored the victims’ voices and focused too much on the police.

In a statement, the Vancouver police department said it “deeply regrets anything we did that may have delayed the eventual solving of these murders.”

“It may also come as small consolation to those who still grieve that we are committed to learning from our mistakes and have taken and will continue to take steps in the future to ensure that the same type of errors are never made again,” the statement said.

Oppal’s report makes a number of recommendations, including better training for police officers who deal with women in the Downtown Eastside, more services for sex workers and other vulnerable women, and some form of regional policing in the Vancouver area.

Vancouver police said they’ve already implemented some new measures, such as a restructuring its Missing Persons Unit and beefing up its outreach programs that deal with sex trade workers.

Investigative blunders

Although reports of missing women began to emerge in the 1980s, it wasn’t until 1991 that the disappearances caught the authorities’ attention, Oppal said.

There were discussions among police investigators about a possible serial killer, but there wasn’t enough evidence to support that theory. Meanwhile, more women went missing.

Oppal said the first major investigative blunder occurred in 1997, when Pickton picked up a sex worker in Vancouver and insisted on going to his farm, where he attacked her.

The woman was so badly injured that she died twice on the operating table, but she managed to survive. Pickton was charged with attempted murder, but prosecutors eventually stayed the case.

Oppal said that victim told police that Pickton must have taken other women to his farm – she had seen hair brushes and other personal items at his place.

Instead of treating the victim’s story as a major red flag, police dropped the ball, Pickton said.

When police ultimately decided to try to interview Pickton in 1999, they phoned his farm and talked to his brother, who convinced them to wait until the rainy season, when they wouldn’t be busy.

That was a “colossal failure,” Oppal said.

As the police investigation dragged on, Downtown Eastside sex workers and other women who were in Pickton’s path were exposed to “immense harm,” Oppal said.

The women were “legally entitled” to know that a serial killer may be in their midst, he said.

With files from The Canadian Press